- About

- Topics

- Picks

- Audio

- Story

- In-Depth

- Opinion

- News

- Donate

- Signup for our newsletterOur Editors' Best Picks.Send

Read, Debate: Engage.

„I could think of nothing but the White Rhino. Never had I been so impressed and at the same time strangely involved with an animal.“

These are the memories of a young game warden, alone at a campfire in the bush in South Africa. His name: Ian Player.

In his 1972 published book "The White Rhino Saga", the environmental activist, who had already become famous, recalled his memories of his beginnings. Player died of a stroke in 2014. His "Operation Rhino" made it into the history books and into the collective memories of many people around the globe that are concerned with wildlife and environmental issues. The fact that there are about 20,000 White Rhinos today is largely due to Player's Operation Rhino.

But would it be repeatable? Could a "New Operation Rhino" be successful today?

As described earlier in our developing story, Koczwara's strategy is based on a '3-pillar-approach'.

“We're trying to stop poaching in the Greater Kruger in South Africa, that's our first pillar. Then we want to establish a bio bank, a cryo conservation facility called Cryovault, which is the second. And the third pillar will be the re-introduction of rhinos in our sanctuary we leased from the state of Zimbabwe."

A group of Black Rhinos in the savannah

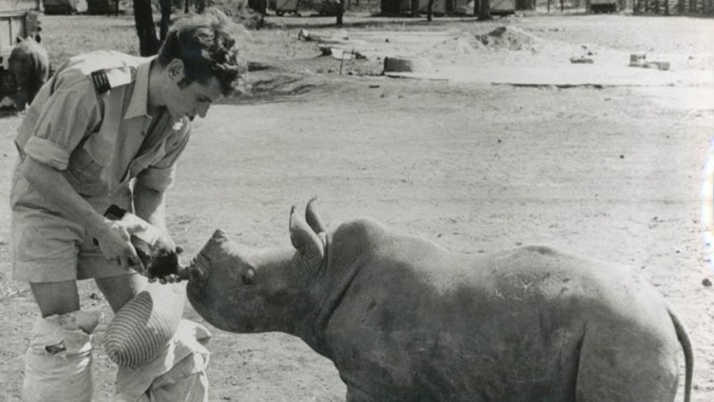

The evacuation and redistribution of threatened rhino groups is still common practice in African countries, where there are still rhinos left. It was one of the core elements of Dr. Ian Player's Operation Rhino.

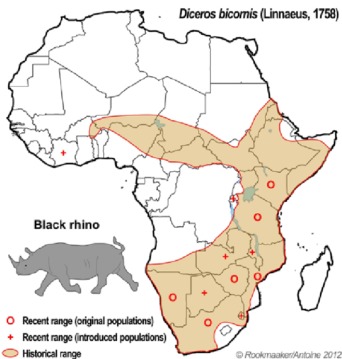

Ralph Koczwara's Rhino Force direct-action conservation organization realises a combination of projects, all designed to save the species through measure which complement each other. His New Rhino Project plans to establish a group of Black Rhinos in Zimbabwe's Lower Zambezi Valley – it is an area where they've lived before and had to be evacuated thirty years ago due to increased poaching pressure. The idea is to bring the Black Rhino back into their natural home range in Zimbabwe. He wants to stabilize and increase their population in a high-security protection zone.

The second core of the former “Operation Rhino” was to sell animals, to give them a value and to foster private property as a base for the flourishing private game parks today. This is considered a promising strategy in South Africa to encourage buyers to protect their "investment" in the best possible way. Despite public debates as to what extend wildlife should be owned privately, even large conservation organizations , like for example the World Wildlife Fund for Nature (WWF), acknowledge this practice as a possible way.

But how do private owners and breeders assess the situation today? South African John Hume is the largest private rhino breeder in the world, currently owning more than 1.600 rhino with close to 200 rhino calves born each year.

“We need to encourage everyone in the country to breed rhino and the only way to do that is to legalise the trade,” says John Humes who filed a lawsuit against South Africa's domestic trade ban on horn – and won at the country's highest court last year. He and many other breeders are in favor of a complete lifting of the international trade ban in horn imposed by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). Their argument: Only the legal sale of horn can cover the immense cost of rhinoceros breeding. In fact, several private breeders have announced that they will stop breeding if the ban is not relaxed. According to the breeders, if the ban is not lifted it is not the breeders but the poachers' syndicates who continue to make high profits - and continue poaching.

But how far can the stocks of rhino be decimated? Scientists talk about the Minimum viable population (MVP), which is the lower bound on the population of a species, so that it can survive in the wild. How many rhinoceros are needed to maintain a viable population and grow resilient genetic diversity? "Ian Player has proven that a stock of just under 500 animals can be enough," says the German veterinarian and specialist for assisted reproduction of large mammals, Dr. Imke Lüders.

However, at the end of the 19th century, when the first sanctuaries were established in South Africa, only a few dozen animals were assumed. And that number was obviously sufficient.

“In Indonesia, there are currently just about 60 individual Javan and Sumatran Rhinos left, respectively – and scientists still think they can save the species”, Lüders says. Surprisingly, even today it cannot be taken for granted to have the exact number of animals at hand, as a closer look at Indonesia shows. The last remaining Javan rhinos are found only on the western tip of the island of Java, their number was estimated at about 60 animals, but exact counts were initially not available. Javan rhinos range over large areas of dense and swampy rainforest, so researchers were having all sorts of problems tracking them accurately. Instead they found tracks and dung, which helped them understand the habitats that rhinos use, but are rarely good indicators of population size. But to have precise numbers of population at hands is crucial to approach the problem of possible threats of extinction to authorities in order to raise awareness and to ring alarm bells. A team of international researchers finally managed to count the remaining Javan Rhino to 62 individual animals by using latest technology of camera traps.

In fact, the use of modern technology makes it possible to monitor animals more closely and more precisely. National parks and other protected areas can now be surveyed much more effectively, not only with satellite imagery, but also with drones. And with new transmitters that are planted just under the skin of the rhino, the movements of individual animals can also be traced around the clock and also diagnose symptoms such as stress by monitoring the heartbeat, which in turn can point to diseases or attacks from poachers.

Latest developments in scientific research are supporting conservationists and breeders alike with better means to stabilize and increase the population of animals.

"The advances in molecular genetics today make it possible to analyse the relatedness of rhinos and to determine more precisely which bull should fertilize which cow in order to maintain genetic diversity"

veterinarian Dr. Imke Lüders explains.

"And better understanding of rhino reproduction physiology will be helpful to improve ex-situ breeding efforts, ie to set the best timing to introduce a rhino bull and a cow for mating through hormone monitoring. Hormone monitoring may also help to determine the birth timeframe so that the veterinarian can be present in case assistance is necessary. And when putting up sperm banks to secure viable genetic diversity, the improved knowledge of how to freeze rhino sperm is essential too, Lüders continues.

In addition, the fact that many more well-trained veterinarians such as Dr. Lüders are available to accompany breeding and conservation programs for endangered species such as rhinos poses a great advantage. Immense progress has been made in veterinarian research in recent decades, as evidently shown by the steadily increasing number of promising scientific publications, as well as the networking of scientists at large conferences.

New insights into medicine and physiology of rhinos benefit breeding efforts around the globe. For example, there was a new vaccine developed by veterinarians from South African rhino breeder John Hume against Clostridia, a bacteria that may cause severe and often fatal enteritis in rhinos, but may now be less dangerous to the animal, if the rhino is vaccined. The same applies to many other medical advancements, such as blood analysis to diagnose health conditions. But also improved knowledge on dietry requirements , at least for animals that live in the custody of humans, as in zoos, have shown to improve the calving interval, which means more baby rhinos within the lifespan of a rhino cow.

Endangered wildlife, and rhinoceros particularly, suffer from the shrinkage of their habitat. The fencing of pasture and arable land is to be mentioned here, as well as the trend towards monocultures in modern agriculture, but also the urban sprawl, the ever increasing expansion of cities, urged by the increase in population especially in Africa, and also the fragmentation of large wilderness areas for better transport routes, such as highways or railway lines.

Illustration: Range contraction of large herbivores in Africa by Researchgate

As the WWF points out, around half of the world's original forests have already disappeared, and they are still being removed at a rate 10x higher than any possible level of regrowth. As tropical forests contain at least half the Earth's species, the clearance of some 17 million hectares each year is a dramatic loss.

So whoever wants to provide for stable populations of wildlife, must provide the appropriate conditions, ie an intact habitat.

Upcoming chapters of our developing story will show the importance to involve communities that traditionally share their habitat with wildlife, and what they can do to help their animal neighbors to survive – and how they can ultimately benefit themselves.

Images: Black Rhinos in the savannah by Inhabitat; John Hume's rhino farm by Fight for Rhinos; Dr. Imke Lüders at workplace by Frank Odenthal; all other images by Hemmersbach Rhino Force