- About

- Topics

- Picks

- Audio

- Story

- In-Depth

- Opinion

- News

- Donate

- Signup for our newsletterOur Editors' Best Picks.Send

Read, Debate: Engage.

Once upon a time when God made all the animals he had them all make their own skins. To this effect, he gave them all a needle to sow them with. But the Rhino, being a bit clumsy, lost his needle and had to use a thorn instead. This is why his coat is so badly fitting. Tragically, he thought he might have swallowed the needle and this is why he can often be seen kicking his dung about. He is looking for his needle still so he can make a better coat.

Zambian Folk Tale

Most of us will say, yes, I’ve known rhinos since I was a kid, I grew up with stories of them, they played a part of my childhood, just like the elephant, the lion, the tiger and the giraffe. It’s hard then to imagine, that at some point, maybe even during our own lifetime, they might not be here anymore. It’s the iconic character embodied by the rhino that makes it so special. It has always been here, as long as I can possibly think back.

The presence of the rhino is also ample in the figurative historical sense. When Marco Polo encountered rhinos on Sumatra in 1292, he was disappointed at first, thinking he had finally discovered unicorns. But the appearance of the Sumatran rhinoceros – with its hairy skin, feet like an elephant, and a thick, black horn on a ”pig-like head“, as he wrote – did not at all fit to that idea of a pure, white mythical creature.

However, it took until the 16th century to show the world a portrait of a rhino, which should henceforth be part of our collective memory and influence all further displays and imaginations of the rhino. When the German Renaissance painter Albrecht Dürer introduced his work ”Rhinocerus“, a woodcut, in 1515, thanks to the then recently developed new printing methods, it quickly became a mass-produced art display with large runs. Today, the ”Rhinoceros“ is one of the most recognisable Renaissance works of art.

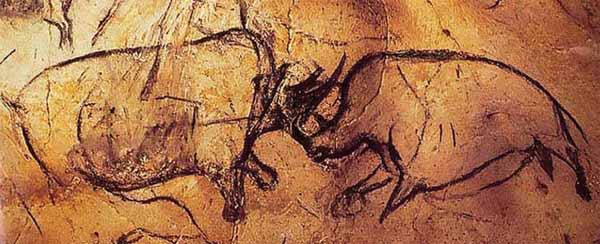

Dürer’s work, however, was by no means the first display of a rhinoceros in history. The earliest rhino depiction known today was found in 1994 by French researchers near the southern French town of Vallon-Pont-d’Arc, in the Chauvet Cave. The cave paintings found there, which also include the displays of woolly rhinos, were backdated to be up to 37,000 years old; they are therefore the third oldest known cave paintings in the world (after the El Castillo Caves in Spain and the Leang Petakerre Cave in Indonesia). The rhino pictures in that cave in France go back to the nursery of humanity itself, the Stone Age.

In Pete Clemence’s memories, the rhino is always present, too, and not only from children’s books. When he grew up in southern Africa about sixty years ago, rhinos were a ubiquitous part of the wildlife. He recalls:

„IF WE RAN INTO A BLACK RHINO – AND THAT WAS VERY COMMON THEN, IT WAS NORMAL – THERE WAS ONLY ONE THING FOR US TO DO: GET UP ON A TREE AS FAST AS POSSIBLE. RUNNING AWAY WAS POINTLESS SINCE THE RHINO IS FASTER.“

In his childhood, there were many black rhinos in southern Africa. Today, there are only about 5250 animals left, most of them living in Namibia and South Africa. In Zimbabwe, where Clemence currently inhabits a tent in the middle of a national park, alone, among all the wild animals, he is a legend in the fight for the survival of rhinos.

Pete Clemence rescues a baby orphan whose mother was just killed by poachers

Thirty years ago, Clemence was part of a team of wildlife conservationists who evacuated the last Black Rhinos of the Zambezi Valley on the border between Zimbabwe and Zambia and brought them inland in a successful bid to save them from extinction.

But what about today’s rural communities in southern Africa? The iconic species, like elephants, lions and leopards largely roam highly protected areas, guarded in hopes of saving them from poaching and extinction. The locals, who only a few decades ago shared their habitat with the animals, now have to visit a park, like the many tourists from overseas; sometimes they even have to pay entrance fees. But many African children cannot afford that, especially in poor rural areas. Instead, they grow up next to these great, wonderful wild animals, without ever having seen them in real life. They have lost touch with their local, hereditary wildlife.

A ranger in South Africa once described the case of a boy who, together with his classmates, went on a school trip to the Kruger National Park, where he saw a rhino for the very first time in his life. He put his hand on its thick skin – and backed off in alarm, shouting

“It’s breathing!“

Local communities could play an important role in sustaining such iconic animals while benefitting from it – if they are closely involved in the transition processes – from trophy hunting to sustainable tourism.

It seems paradoxical, but for many of us who know these iconic creatures only from books, movies, and from the zoo, the rhino, at times feels more tangible than for those who grew up in proximity to them. And it seems just as paradoxical that although we are so close to this species, so familiar; perhaps even taking their existence for granted, we may not be able to save them from extinction.

This archaically iconic animal, a living being who doesn’t have any natural predators except ourselves – needs that we shine a light on its story, and the many stories of those who are working to protect its life on earth, alongside those who poach it for survival.

We should reach our hand to those who do, or, as the children of the Underberg School in South Africa put it:

They say for everything there is a season

The ring of life revolves as time goes by,

But Rhinos are dying for no natural reason!

It makes us hang our heads in shame and cry.

Protecting our rhino is our duty

We can't afford to stand idly by,

Gotta stop their horns becoming Eastern muthi,

Why, oh why should rhinos die?!

It's because of man's greed and because of man's vanity

Come on now Asia, stop this insanity!

Why, oh why should rhinos die?!

Our wildlife is the pride of our nation

Come on now, stop this exploitation!

Why, oh why should rhinos die?!

They can't survive without us intervening

They won't survive if we turn a blind eye!

Does the sanctity of life have no meaning?

Why, oh why should rhinos die?!

The story of the rhino has many facets and connects to global politics and local activism in more ways than might be visible to the onlooker.

It is no coincidence then, that we have dedicated FAIRPLANET’s first long-term constructive journalism project to the rhino population, although there are currently more than 1.7 million other endangered species on our planet. But how are we going to protect the Sowbug Rice Rat, the Swazi Rock Snake or the Smooth Dainty Frog from extinction, whose appearances (or disappearances) are much less spectacular? As Pete Clemence put it:

"If we lose the rhino, we will lose them all."

If we can not save such a unique animal, a close friend from childhood, a living dinosaur that has populated the globe for over 50 million years, we can not save any other species. The demand for rhino horn already far outweighs the supply, which leads to people asking the question 'are rhinos extinct?' If the supply is exhausted and the rhinos extinct, the demand will turn to the next wild animal, and it in this economy it seems that the more threatened creature, the better.

There are already hints that in the future, teeth from hippos could find a market or generate it. Hippos are still relatively abundant in Africa, even in the wild, but the demand for rhino horn skyrocketed only about ten years ago, and today they are on the brink of extinction. The more threatened, the more attractive. The more lucrative for the poachers. And the Red List is growing steadily. But the list is not endless. If the current mass extinction of species is not stopped, the party on our beautiful blue planet will eventually be over, even for us humans. Then there would be no one left to remember animals like the rhino, not even from children’s books.

Let’s not get this far!

Credits:

Woolly Rhino digital artwork by Daniel Eskridge

Albrecht Dürer's "Rhinocerus" image of woodcut print by Wikipedia

Chauvet Cave painting by Wiki Commons

Running Rhino by Creative Commons

Pete Clemens saving a baby Rhino in the bush by Bryce Clemens

Volunteer from Bambisanani project with a South African child and rhino book

Rhino horns, Tsavo, 1976 by DSWT