- About

- Topics

- Picks

- Audio

- Story

- In-Depth

- Opinion

- News

- Donate

- Signup for our newsletterOur Editors' Best Picks.Send

Read, Debate: Engage.

The Argentinean province of Tierra del Fuego in Patagonia became the first place in the world to prohibit open salmon hatcheries due to its high level of environmental damage. But local governments and companies encourage other rearing systems for native sea and river fish species. Is it possible to combine sustainability and profitability in the fish farming?

© Fundación Rewilding Argentin

© Fundación Rewilding Argentin

In the southernmost tip of Argentina, the two largest oceans in the world, the Atlantic and the Pacific, are connected by the Beagle Channel. The strait through which Charles Darwin navigated on his way to the Galapagos Islands, where he would finally write the Theory of Evolution, links the two huge bodies of water and constitutes a unique ecosystem. There, there is an amazing biodiversity of fishes, mammals, birds and underwater forests.

This magnificent natural setting has been under threat since 2018, however, due to attempts to install salmon farms, an exotic species for the region, based on techniques that proved to be harmful to the environment in countries like Chile and Norway.

The project was finally halted in June 2021, when the province of Tierra del Fuego unanimously approved an unprecedented law prohibiting salmon farming in natural waters. However, the promoters of the law assure that this decision does not hinder the possibilities of farming salmon or other aquatic species, both in Patagonia and in other regions of Argentina. On the contrary, there are several projects in the country for native fishes, both sea and river, which are producing good results and are based on environmentally friendly and respectful methods.

Map of Tierra del Fuego, Argentina. Source: Encyclopedia Britannica.

"The law passed in the province is not anti-production,” explains Carlos Cantú, Secretary of Fisheries of Tierra del Fuego. “Although it explicitly establishes the prohibition of salmon in natural waters with the methods used in other countries, it leaves open the possibility of farming this species on land, with systems that use water recirculation and do not pollute, keeping our natural environments safe."

The plan is to maintain the pristine waters of the Beagle Channel in order to promote other crops, such as mussels or trout. The province itself has a fish-farming station where trout are raised to stock the lakes and rivers, which helps promote its tourist attraction.

These species are widely valued by locals, who choose them over the pink salmon that was intended to be farmed mainly for export to markets in the northern hemisphere. In the city of Ushuaia, for example, many restaurants have been announcing over the past few years that they would not serve salmon, as part of a campaign that attracted well-known chefs and gastronomic entrepreneurs and then spread to the whole of society.

"Achieving this level of consensus was not easy because there were political interests and large capital from foreign governments,” says Martina Sasso, coordinator of Sin Azul No Hay Verde (No Blue, No Green), the marine conservation program of the Rewilding Argentina Foundation, which has played a leading role in the campaigns against salmon farming in recent years. “It took more than three years of intense work and permanent actions, but it was achieved and we can say that we reached the stage of voting and approving a provincial law with all sectors aligned: state officials, local businessmen and neighbours said no to salmon farming."

© Fundación Rewilding Argentin

© Fundación Rewilding Argentin

The national government criticised the decision taken in the Patagonian province. The Minister of Production, Matías Kulfas, stated to the press that he considered the ban "a mistake." Nonetheless, this did not intimidate the people of Tierra del Fuego, who firsthand witnessed the experience of their Chilean neighbours and the socio-environmental devastation suffered by the country.

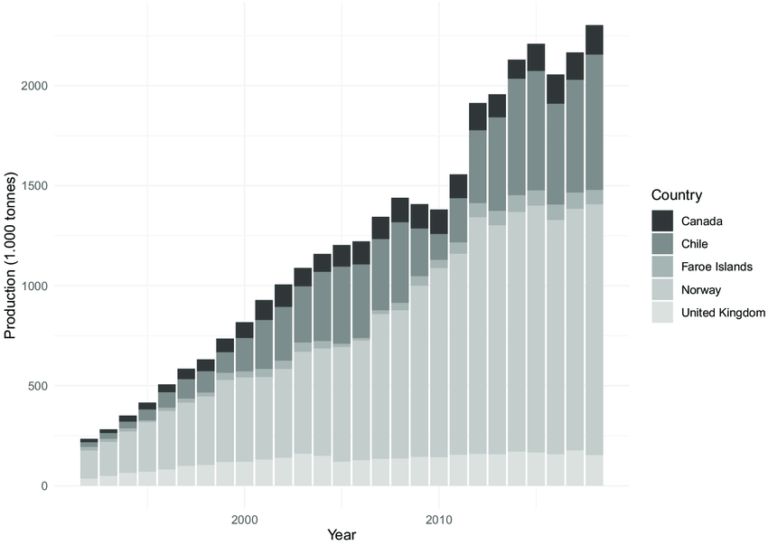

Top-five producers of Atlantic salmon by country. Source: Kontali Analyse AS.

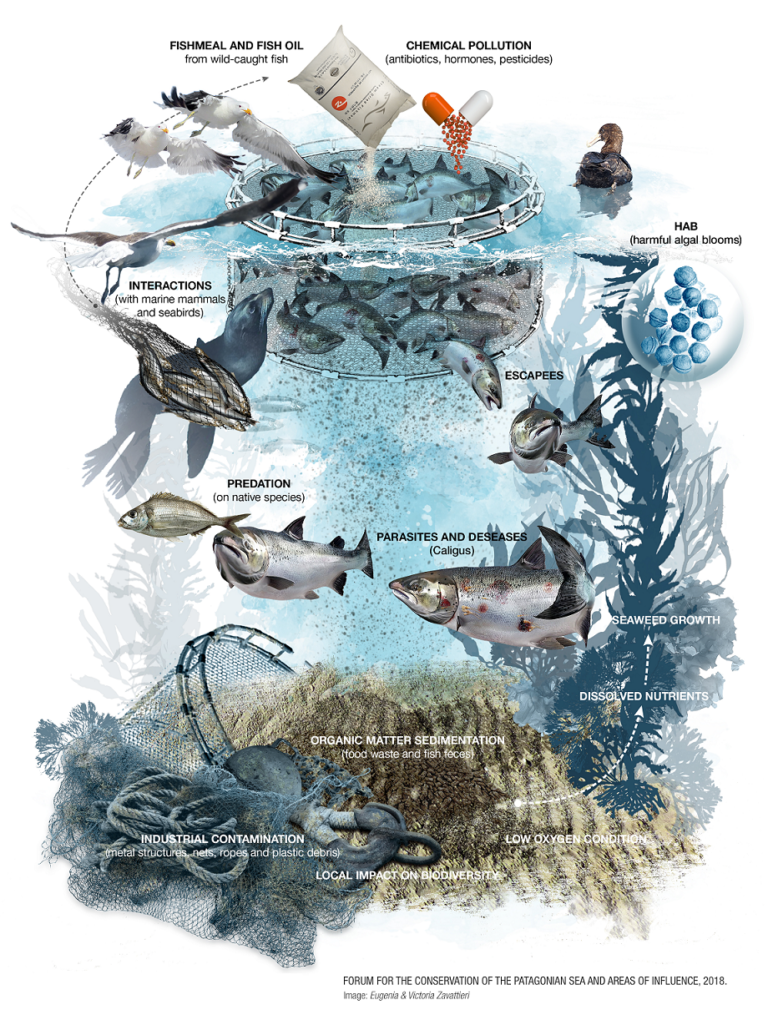

Chile is the world's second-largest producer of salmon and, after more than 30 years of using these techniques, is beginning to experience the serious consequences of the industry. Some of them are the abuse of antibiotics, pesticides and other chemicals, the escape of salmonids and the introduction of exotic species into natural environments, the introduction and spread of diseases and the accumulation of solid and liquid waste on the seabed.

In Tierra del Fuego, the idea that the law has put a brake on a productive matrix was rejected. "Salmon farming can be done, but on land. It is a much more expensive system, but it is possible, other countries do it and it is what will allow us to keep our ecosystems intact," said Martina Sasso, pointing out that there are several such projects underway for bivalve farming.

Image: Eugenia and Victoria Zavattieri. Source: the Forum for the Conservation of the Patagonian Sea and Areas of Influence (2018).

Learning from public officials and business people about how to correctly promote native species is something new in Argentina, and environmentalists are enthusiastic about it. While in Patagonia salmon farming was banned to protect the environment and native species farming is being promoted, another good solution comes from the other side of the country. In the province of Chaco, a private company is developing an innovative fish farming project that combines fish farming with rice cultivation.

The company was previously questioned about the use of agrochemicals in their fields and the effects these had on the surrounding populations and on the environment. After that, they decided to carry out studies about these impacts, which demonstrated that they were capable of raising fish in the same areas where the rice was grown. The species they chose was the pacu, a river fish highly valued for the taste of its meat and its high protein value.

Fish consumption in Argentina is quite low: around 5 kilos per inhabitant per year, while the world average is 20 kilos per person per year. This gap widens in the northern provinces of the country, which have the highest poverty rates.

"Our products are especially dedicated to the domestic and regional market. We produce around 400 tonnes per year, which are used to manufacture 12 types of products that go directly to supermarkets and shops," explains Marcos Meichtry, one of the managers of the family company that set up this system, Teko. "When we started, there was no similar type of product in the local trade and we can say that it is a success that has a lot of potential to be extended, both to other provinces and to neighbouring countries, such as Bolivia and Paraguay, which do not have access to the sea and have a lot of demand for fish."

Fish farming is a broad sector that has a lot of potential for development in Argentina, a country of enormous territory and a great wealth of fish. The challenge for the future is to determine the ultimate direction and objectives of these activities: favouring profitability and the demands of external markets or respecting the environment and caring for native species.