- About

- Topics

- Picks

- Audio

- Story

- In-Depth

- Opinion

- News

- Donate

- Signup for our newsletterOur Editors' Best Picks.Send

Read, Debate: Engage.

Algae are of key importance to marine ecosystems and produce half of the planet's oxygen. In Chile, they are being predated to be commercialised in an industry that trades a million tons of algae worldwide. The South American country contributes at least 40 percent of that million.

© Lance Gomez. A local resident carries baskets full of seaweed.

© Lance Gomez. A local resident carries baskets full of seaweed.

Chile has an extensive coastline of 6,435 kilometers which is home to a great variety of flora and fauna. In Caleta Los Bronces, a town of 100 inhabitants located in the Atacama Region, lives and works Nibaldo Yáñez, a fisherman who has been collecting seaweed from the shore for 15 years. Yáñez’s job is simple, yet it requires a lot of physical dexterity. He waits for the natural death of the algae that after the tide strands on the shore. Then he collects it, carries it on his shoulders away from the sea, dries it for several days and finally sells it to companies that market it abroad. On a good day, Yáñez can collect up to 500 kilos of seaweed, which sells for around US $0.5 per kilo.

Yáñez says that in the 500 kilometers of coastline that separate Chañaral, a city located in the northernmost tip of the Atacama Region, from the town of Chañaral de Aceituno, in the south of the same region, "every kilometer and a half you see a person extracting algae."

"We are the first country in the world to contribute biomass from algae from natural grasslands,” Fadia Tala, Executive Director of the Technological R&D Center on Algae and Other Biological Resources and Associate Researcher of the Millennium Institute in Coastal Socio-Ecology, told FairPlanet. Tala studies the activities of fishermen that remove, harvest or cut algae that are growing in their natural environment. The specialist explains that a million tons of algae that come from natural grasslands are traded worldwide, and Chile contributes at least 40 percent of that million, mainly brown algae.

Algae as a species are incredibly important for life on Earth. The Center for Dynamic Research of Marine Ecosystems of High Latitudes estimates that they produce 50 percent of the planet's oxygen, even more than the amount that terrestrial forests provide. Furthermore, “Over 100 species have been counted that live associated with the forests of large brown algae,” said Tala. “If we overexploit them, it is most likely that we are also overexploiting other resources or other species,” explained César Astete, Director of Fisheries at Oceana, an NGO working on ocean´s conservation.

Despite the importance of algae for the marine ecosystem, in Chile the resource is being predated to be commercialised in an industry that is considered the first fishery in the country. This September´s Fisheries and Aquaculture Sector Report indicates that in July 2021 the extraction of algae was valued at US $60 million. The most important destination was China, which accounted for 79.2 percent of exports.

Claudio Báez, National Director of Sernapesca, a governmental institution dedicated to overseeing compliance with fishing regulations, explains that illegal fishing of algae is perpetrated by people who extract the resource without being registered in the Fisheries Registry. Furthermore, and most worryingly, they do so using the barreteo technique, which is, "to extract the algae from its basal disk with the help of a stick or barrette, despite its prohibition under certain circumstances," said Báez."This is one of the most pressing problems that we must face mainly in the northern part of the country," he added.

Oceana´s expert César Astete ensured that before 2010, the extraction of algae occurred mainly through harvesting, as Nibaldo Yáñez still does. "There was little barrage, which is a relatively new problem in the management of the algae fishery," he said. However, the expert pointed out that today, due to the growing scale of the activity and high prices, divers are cutting the algae with barrettes. Indeed, Astete recalled that one of the things that divers told him last time he was in the area, was that now they are having to dive deeper to remove the algae because one cannot find it as easily as before.

© Rachel Clara Reed

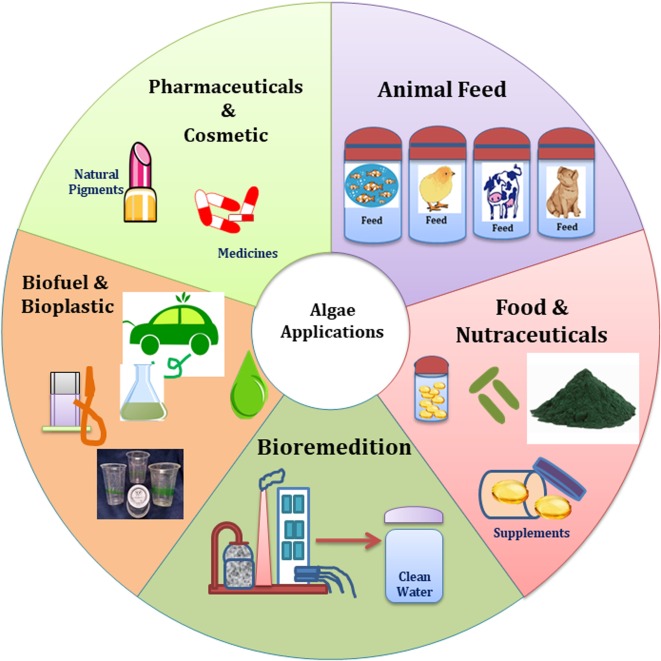

What explains the commercial relevance of algae is alginate, a compound found in the basal discs of this resource, which is used worldwide in the cosmetic, food, pharmaceutical and textile industries, among others, since it allows agglutination. This compound is used to make dental molds, pet pellets and creams.

"Worldwide, it is recognised that the alginates that come from the brown algae of Chile are among the best alginates in the world, due to the characteristics that they can give of viscosity, to emulsify or thicken substances", explained Fadia Tala. The specific characteristics of brown algae are triggered by the Humboldt Current, an icy current that bathes the Chilean coast and makes it highly productive.

Source: Journal of Water Process Engineering, Vol. 40, April 2021 191794 via ScienceDirect.

"Much of the extraction occurs in remote or difficult-to-access areas, where our presence is not permanent," explained the National Director of Sernapesca. The expert adds that controlling illegal extraction of algae is a challenge due to the number of actors that participate in the productive chain of algae extraction. “You have the algae fishermen, who work with intermediaries who are the ones who move these algae to processing plants. Then you have the processing plants and the exporters. The regulation that the State has is mainly at the bottom of the chain, not at the top," argued Báez.

"If you start looking at the complete chain, you find that in the intermediation or purchase, there are also behaviours that may constitute illegalities. For example, when the intermediary or the buyer buys seaweed without having the accreditation of legal origin, that is, without knowing where it comes from," explained César Astete, adding that if one moves forward in the chain, it may be found that there is also illegality in the processing plants. He added that often the National Fisheries Service cannot establish traceability of algae because the processing plants are unable to report what its source was or whom they bought it from.

Nibaldo Yáñez agrees that the issue of lack of oversight is serious. “In the Atacama Region there are 20 Sernapesca officials to safeguard 500 kilometers of coastline. Here in the province of Huasco, where I do my work, there are three officials and they do not only control algae extraction," he said.

The number of people extracting algae has increased since 2010: the price per kilo of algae skyrocketed. The higher the price, the more people who carry out the activity. "This is one of the easiest jobs related to artisanal fishing. You don't have to get on a boat, dive, you don't have to go out to sea," explained the fisherman.

The rise in regional unemployment due to the pandemic also increased the number of people illegally fishing algae. “In situations of unemployment (in small mining, for example, where unemployment grew as a result of the pandemic) many people dedicate themselves to illegal extraction to generate income,” said Claudio Báez of Sernapesca. “We have also detected that an important part of the illegal extractors have judicial records or are irregular immigrants, so perhaps they choose this activity due to the difficulties in finding work in other sectors of the formal economy."

With the aim of mitigating the illegal activity around the extraction of algae, Sernapesca established limits on extraction to stop "super extractors": authorised algueros that declared the extraction of some illegal agent as their own so it can be sold.

However, for experts this is not enough. They call for governmental investment in scientific research to study the real effects of the over-extraction of algae. "This is the fishery that has had the largest expansion in recent times and it turns out that we do not have the necessary budgets to do the research that is required today," said César Astete of Oceana. "It cannot be that one of the largest fisheries in Chile - and with the highest export figures - continues to be a fishery with poor data."

In addition, Sernapesca is constantly implementing information dissemination and training campaigns. And yet, Yáñez claims that they have never been trained by the agency. "Nobody who has made a life on the coastline, who has built a house or educated their children through this work, would want to kill the small amount of algae that is left," concluded the fisherman.