- About

- Topics

- Picks

- Audio

- Story

- In-Depth

- Opinion

- News

- Donate

- Signup for our newsletterOur Editors' Best Picks.Send

Read, Debate: Engage.

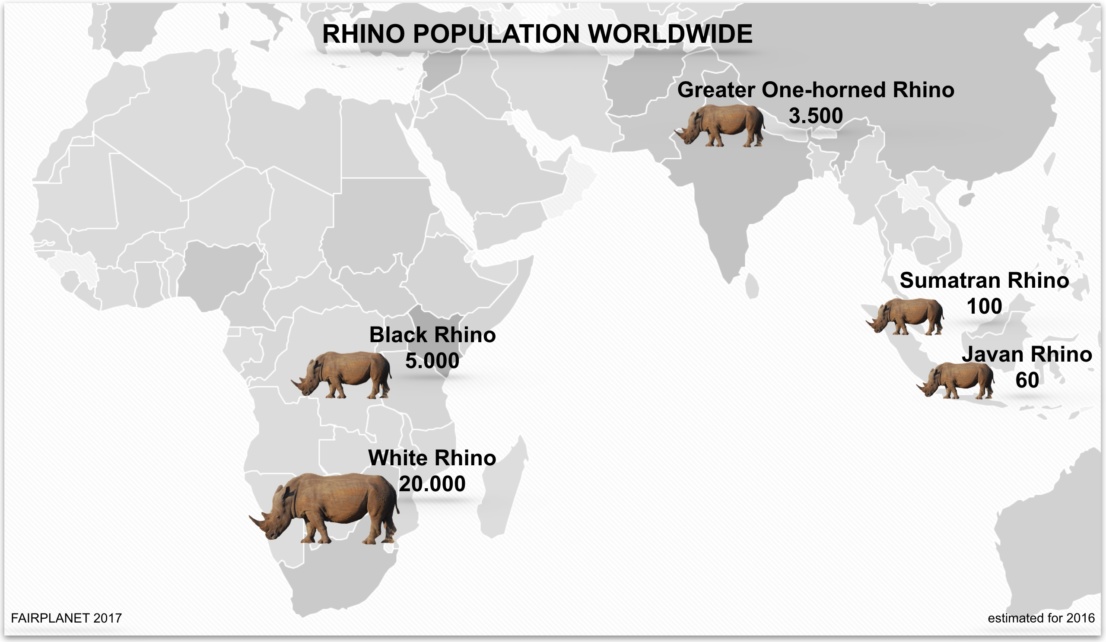

Looking at the numbers, there is no reason for optimism. According to recent estimates, no more than 30,000 rhinos are left on earth, including about 20,000 white rhinos and 5,250 black rhinos in Africa, as well as about 3,500 Indian rhinos and no more than 100 Java and Sumatran rhinos in Indonesia respectively.

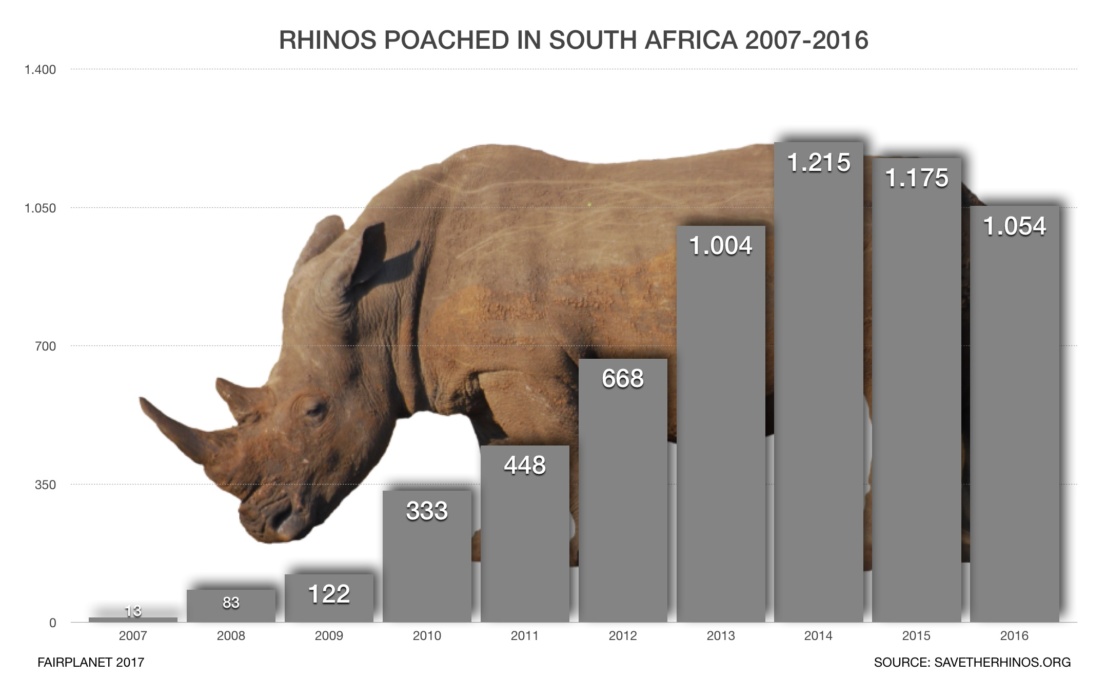

Extrapolating the numbers of casualties by poaching, with demand for rhino horn skyrocketing in the last ten years – especially in China and Vietnam – rhinos could disappear from our planet within a decade. It's no wonder people are already asking 'are rhinos extinct?'

Is there a glimpse of hope left for these archaic creatures? Or will they fall victim to human greed after surviving more than 50 million years on the planet?

Although they have no natural enemies, rhinos have been on the verge of extinction before, during the middle of the last century. That time it was the commitment of a South African conservationist named Dr Ian Player that saved the rhinos from extinction. Player launched his now famous 'Operation Rhino' in 1952, evacuating the last Southern White Rhinos – during which time there were only 200-300 of these animals left – from the Umfolozi game reserve to various national parks in southern Africa, especially the Kruger National Park, but also to zoos worldwide.

Two important elements of 'Operation Rhino' were crucial: the fact that not single animals, but breeding colonies of rhino were distributed, and secondly, that he was allowed to sell the animals to national parks and zoos instead of giving them away for free; so there were buyers, who therefore had a monetary interest in preserving the animals. The results proved him right, the stocks were constantly recovering. Today's population of about 20,000 Southern White Rhinos in Africa is inextricably linked to the work of Ian Player and his 'Operation Rhino'. Player died of a stroke in 2014.

Could the strategy of a new 'Operation Rhino' continue to be successful, even today? Then as much as now, South Africa is in under pressure and global limelight to save the rhinos. Of the 20,000 white rhinos in Africa, 18,000 live in South Africa, about 7,800 in the Kruger National Park, which is by far the largest population in the world.

On the ground, there is a complex and intertwined conflict taking place heavily armed private security forces and special units of the police alongside the military on the one side and on the other, gangs of poachers, equally heavily armed by the Asian syndicates.

Whether the fight for the rhino population in the Greater Kruger can be won by military means is questionable. The boundaries of the 20,000 square kilometre area appear to be too patchy, despite the use of the various anti-poaching units and latest surveillance technology.

A RHINO FORCE anti-poaching ranger shows the areas of defence in Greater Kruger

The strategy to make rhinos a private asset – following in the footsteps of Ian Player during the time of 'Operation Rhino' – is considered by many Conservationists, including the World Wildlife Fund, as a successful model.

Ralph Koczwara, a German IT-entrepreneur and founder of Hemmersbach Rhino-Force, a private anti-poaching and direct-action preservation organisation, operating around Greater Kruger in South Africa and at the Lower Zambezi valley in Zimbabwe, is currently preparing what could be called a 'new Operation Rhino'. He says:

"The task is complex. We need to protect and preserve the animals, work with communities and authorities to achieve the sustainability of wildlife. All that buys us time until we break the demand."

Koczwara's plans: to bring back the black rhino into the Lower Zambezi Valley. 2,000 Black Rhino Minor once lived about 30 years ago. Almost all of them were killed by poachers during the 1980s, 30 animals were then evacuated further inland of Zimbabwe in an attempt to save the bulls from their nearing fate of extinction.

The social entrepreneur will own the returning rhinos, buying them from Southern African breeders and bringing them to Zimbabwe, into a well-protected zone inside a wider area of recreational land.

Ralph Koczwara on the idea of transforming Lower Zambezi Valley from intense hunting to a safe place for rhinos

In the area, according to Koczwara's plans, the group of rhinos will find a safe place to mate and to prosper, and – from a wider perspective – to create a genetically viable and diverse population of black rhinos.

Lower Zambezi Valley, Zimbabwe

View from a RHINO FORCE air patrol flight over Lower Zambezi Valley

The world's largest private rhino breeder, South African John Hume, sees another, more controversial approach as more promising, though it would be quite a breach of taboo and a departure from previous anti-poaching strategies: the complete legalisation of horn trade. He says: “We need to encourage everyone in the country to breed rhino and the only way to do that is to legalise the trade.”

Hume and other private breeders at the Cape say the big expenses faced by breeders today – high-security fences, security guards, veterinarians, medicines, food – cannot be covered in the long run if they're unable to sell their horns – which they get legally as part of their breeding and farming activities – to Asian buyers. Up to $800,000 for a ten pounds horn is the current price on the Asian market.

This sum, breeders argue, should not be left to the syndicates, but to them, the breeders themselves, to invest the money in the expansion of their stocks, thus ensuring the conservation of the species.

Whether poaching can be stopped by legalising trade seems questionable. The demand in Asia might prove to be too large to be legally matched by private breeders. The price of horns is therefore likely to remain high, and thus the incentive for the syndicates to get hold of that huge amount of money continues to be equally high.

Legalization in a context of state-controlled trade, comparable to the legalisation of marijuana in some countries, with horn DNA samples and authorised issuers and traders, could be an alternative. But there are certain natural limits to any legal offer of the horn because a harvested horn takes about a year or two to grow again. So, whether the breeders can meet the enormous demand from Asia, has to be cautiously analysed.

Many organisations, including the World Wildlife Fund, believe local communities are key to the success in protecting rhinos. Rural communities, even those in close proximity to the National Parks, have in many places lost contact with the wildlife in their neighbourhood; many children have never seen a Rhinoceros in their life.

And even worse, children whose fathers are convicted and arrested as poachers might ultimately blame the animal for their fatherless childhood. An empathic connection to the animals is unlikely to grow within such a vicious cycle.

However, if the communities are integrated, for example in the transition process from hunting to sustainable tourism, and participate in the profits, they might recognise the value – if only a monetary one – of wildlife. Some conservation activists even suggest that the communities themselves should become owners of the animals in order to tackle the attraction of easy poaching money with an alternative legal and long-term perspective. But here, too, the question remains: if the potential income of eco-tourism could compensate for the temptations that the immense price for wild horn offers.

Also, one should not underestimate the importance of schools and children. Educational projects such as the Chirundu School Project – we visited this school in Zimbabwe and will report about this project in a later episode –, which involves children in conservation programs can play an important role in raising awareness among them, their families and communities.

Therefore, many consider the approach of breaking the demand for horn in Southeast Asia to be the most promising. But what could such a strategy look like?

For the Wildlife Justice Commission (WJC), an NGO based in Amsterdam, it is clearly a social solution that is needed in those demand countries, like China and Vietnam in particular, and it requires a multifaceted solution. The WJC is using intelligence from undercover operations in order to provide support for national and international law enforcement on the ground.

But the organisation is also trying to incorporate initiatives seeking to change behaviours in these countries. The aim is to reduce demand for endangered animals for medicinal purposes, but also as a status symbol. It's a long-term mission for behavioural changes, but if it ever pays off, it would possibly be the most elegant way of getting hold of the poaching problem. No demand for rhino horn, no rhino poaching.

If everything fails, the ice might save the rhino: minus 196° Celsius is the temperature at which nitrogen freezes. It's called Cryopreservation.

The idea is to freeze male semen and female ovules, but also embryos, so that they can be kept – theoretically for eternity. With such a genetic reserve, a biobank of endangered species, the future of the three remaining Northern White Rhinos might have looked a little more promising than it does today.

They're now inevitably facing extinction, although researchers are trying to save the species with some stem cell-based reproduction methods.

Yet this elaborate method is still in its infancy and is, therefore, seen sceptically by many reproductive researchers, such as the German veterinarian Dr Imke Lüders, an expert on assisted reproductions of large mammals.

Whether the final successful method will be the latest laboratory high technology or a return to a harmonious coexistence of communities on the ground; whether it will demand another armed campaign against poachers or a social media campaign against horn as a remedy or jewellery in Vietnam and China, saving our rhinos remains a race against time, with an outcome filled with uncertainty.

Credits:

Lower Zambezi Valley by Rohan Nel

John Hume on his rhino breeding farm by Fight for the Rhino

Hong Kong customs seized a large amount of rhino horn by Bobby Yip / Reuters

Rhino Force Chirundu School Project by FAIRPLANET

Traditional medicine using Rhino horn Vietnam animalrescueblog/Flickr, CC-BY-NC

The Cincinnati Zoo preserves cryo of endangered species at -196 degree Celsius. CryoBioBank by Cincinnati Zoo