- About

- Topics

- Story

- In-Depth

- Picks

- Opinion

- News

- Donate

- Signup for our newsletterOur Editors' Best Picks.Send

Read, Debate: Engage.

| topic: | Rule of Law |

|---|---|

| located: | Chile |

| editor: | Ellen Nemitz |

One year ago, the streets of Santiago and Valparaíso, in Chile, were taken by millions of unsatisfied citizens. The spark for the social revolution was an increase in the price of subway tickets, but the fuel was a series of social injustices associated with an old constitution in place since dictatorship times.

On October 18 the country went once again to the streets to celebrate the anniversary of protests – unfortunately, there was vandalism, but these acts were repudiated by the majority and do not represent the movement; one week later, on October 25, people said yes to a new constitution – a choice represented by 78 per cent of voters – after a postponement of the plebiscite due to Covid-19 restrictions.

What they also said is that Chile no longer should maintain a lack of access to healthcare, education and habitation, for example, besides a poor retirement system – with a capitalisation model, the life post-work period might mean poverty. “Half of the Chilean population does not manage to capitalise enough to reach a minimum pension, which is lower than the minimum wage,” explained sociologist Alexis Omar Cortés Morales to FairPlanet.

The professor of Alberto Hurtado University also assesses that the Covid-19 pandemic has intensified the necessity for a new constitution and of rethinking the society model implemented during the dictatorship until present days. “The question that emerges in a context like this is: what kind of society is best prepared to face a pandemic situation like this? And the answers that can be tried is that taking into account world experience, more supportive and less individualistic societies respond better to the health crisis, as well as more organised ones, but also more egalitarian societies are able to better face this situation," he affirms.

Also, according to him, situations like this demand “a better public structure, with greater capacity for intervention and to protect their society, but also with a more robust investment capacity in public health, in public education, with greater investment in science, etc.” Currently, the Chilean government is doing exactly the opposite. And, because of the constitution, bills which aim to give the necessary protection to the population, especially during the pandemic, did not prosper, showing the deep consequences over society.

The future of Chile is yet to be written. Chosen by almost 80 per cent of people, the way of writing it will be democratic, under a Constitutional Convention with gender parity and indigenous participation, and will take up to two years. Even before the results of last Sunday, Cortés Morales was optimistic with a “yes” victory: "this [disruptive protests and political discontent context] indicates that democracy continues to have a chance. And that the debate that is coming opens up the possibility of rebuilding the relationship between civil society and a new political system,” he evaluated.

From now on, with a new future to come, Chileans have reasons to celebrate and energy to keep taking the streets and influence the constitutional agenda. The road will be long, as the sociologist alerts: “This does not mean that the conflict will disappear. The Chilean institution system is in an extreme decomposition situation, and the current crisis has to be seen as an opportunity to rebuild institutions that allow regaining the confidence of citizens, where democracy does not fear the expression of the wishes of its people but is its expression.”

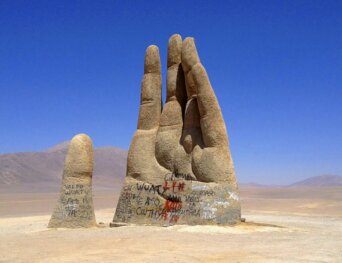

Image by Craig Bellamy, flickr (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)