- About

- Topics

- Picks

- Audio

- Story

- In-Depth

- Opinion

- News

- Donate

- Signup for our newsletterOur Editors' Best Picks.Send

Read, Debate: Engage.

| topic: | Child rights |

|---|---|

| located: | India |

| editor: | Hanan Zaffar |

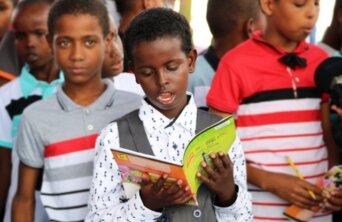

Despite over seven decades of independence, India's education landscape remains marred with systematic inequalities in accessibility, lack of infrastructure, linguistic and geographical differences and discrimination based on caste, religion and gender that routinely manifest inside the classroom.

Many school-going children in rural India struggle with fundamental reading and arithmetic skills despite years of formal education. According to the 2023 Annual Status of Education Report (ASER), nearly one in three eighth-grade students cannot read at the level expected of a second-grader, and more than half cannot perform basic division.

Alarmingly high dropout rates further exacerbate this crisis within India's education sector. According to data from the Ministry of Education, in the 2021-22 academic year, seven states, including Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, and Gujarat, had secondary-level school dropout rates exceeding the national average of 12.6%. While inequalities in education always persisted in India, they were heightened by COVID-19.

In an interview last year, Jaime Saavedra, the World Bank's Global Director for Education, said that "learning poverty" – which signifies a child's inability to achieve minimum reading proficiency and its correlation with the number of children out of school – increased from 54% to 70% after the pandemic.

Children from marginalised groups like Scheduled Castes (SC), Scheduled Tribes (ST), and Muslims are the worst affected. The Sachar Committee Report from 2006 demonstrated that the educational condition of Muslims in India was on par with, or even worse than, the country's most disadvantaged communities. Their marginalisation has only deepened since.

In the 2020-21 academic year, the enrollment of children from SCs and STs in higher education increased by 4.2% and 11.9%, respectively. The dropout rate among Muslim students increased by 8% during the same period. Experts note that such an absolute decline in enrollment has yet to be witnessed for any group recently.

The Muslim community has long faced discrimination and barriers in accessing education and employment opportunities, and experts argue that the current environment, where the community is disproportionately affected by communal violence and hatred, further impedes their socio-economic progress.

In 2020, Delhi, the nation's capital, witnessed one of the worst riots this decade, resulting in 53 deaths and over 400 injuries. The direct consequences of this violence are still evident in the lives of children residing in the northeastern part of the city, hundreds of whom lost access to education after their local schools were burnt down during the riots.

A UNICEF report from 2005 titled "Childhood Under Threat" emphasises that children are among the most severely impacted by conflict, either directly or indirectly. Even if they are not physically harmed, they can suffer deep emotional scars and trauma from exposure to violence, dislocation, poverty, or the loss of loved ones.

Local initiatives like the one led by social activist Aasif Mujtaba and his organisation, Miles2Smile Foundation, aim to reintegrate children affected by the Delhi riots into the education system. Their Sunrise Public School in Delhi's Loni town offers free education to these students.

In its first year, the school enrolled 148 students, 23 of whom had lost their guardians in the violence. While such initiatives provide a glimmer of hope, more still needs to be done to make education equal and accessible, particularly for the children of marginalised groups.

Image by Ismail Salad Osman Hajji dirir.