- About

- Topics

- Picks

- Audio

- Story

- In-Depth

- Opinion

- News

- Donate

- Signup for our newsletterOur Editors' Best Picks.Send

Read, Debate: Engage.

| topic: | Conservation |

|---|---|

| located: | Portugal, Sweden |

| editor: | Abby Klinkenberg |

From the awesome cliffs of the Portuguese Greater Côa Valley to the chilled expanse of Swedish Lapland, the age-old question ‘for love or money?’ rears its ugly and clichéd head. Known for its successful reintroduction of bison to the Transylvanian Alps, Rewilding Europe recently received a nearly €5 million grant from the environmentally focused Arcadia Fund to accelerate its particular brand of radical laissez-faire conservation work known as ‘rewilding’ across the continent. The organisation currently operates nine “rewilding landscapes” and, with this influx of this grant money, plans to expand its portfolio to 15 by 2030. While it publicly projects itself as a non-profit charity foundation - which it is, in part - “Rewilding Europe has also established a [for-profit] limited company (B.V.), which is wholly owned by the foundation.” Rewilding nature with one hand and commodifying it via ecotourism with the other, Rewilding Europe plays both sides of the fertile field and epitomises the double-edged and fundamentally capitalistic nature of rewilding as a practice.

Touted as a sustainable solution to a myriad of environmental challenges, rewilding has recently emerged as a media darling: deus ex machina carbon sinks that reinvigorate fragile ecosystems while mitigating the effects of both flooding and drought. Last year, the UN even celebrated the first ever World Rewilding Day on 20 March (the solar equinox), bringing attention to its defining aspect: “rewilding aims for resilience in nature without human intervention” – a notion that has “[only in the last few years] moved into the mainstream conversation.” Only a few months after this pronouncement, London Mayor Sadiq Khan unveiled the British capital’s very own rewilding fund.

The hype surrounding rewilding projects in Europe seems to reside, at least in part, in its near seamless accommodation of capitalist structures: conversations about rewilding tend to quickly collapse into discourses on eco-tourism. As the New York Times emphasises, ‘core to the rewilding concept is the idea that this “new wilderness,” as it’s sometimes called, will also create new economic opportunities.’ It presents a convenient way for capital to invest in the climate while still ensuring viable profit margins. Rewilding Europe, for example, has fully bought into this notion and sees its connection to capital as a virtue: “By making rewilding commercially investable and economically competitive, [rewilding] models – which encompass everything from the transformation of forests and restoration of peatland to wildlife photography and dam removal – amplify its positive impact.” Predictably, Rewilding Europe has an adjacent travel site that offers seven-night “signature journeys” to the tune of 2,965 GBP per person.

Rewilding Europe’s recent grant will also “help create a pipeline of investable rewilding businesses, involving new finance mechanisms and investment from the private and corporate sector.” In the process of commodifying ecosystems, rewilding distinguishes itself as a deeply Western construct. Any parallels with Indigenous practice are rendered negligible in the cold, hard light of the profit motive.

Amidst these concerns over the utilitarian ethics and corporate leanings of monetisation in rewilding practices, it is hard to buy into the notion that such projects foster healthier relationships with local ecosystems in particular and a deeper respect for the planet in general. It’s a tenuous model to justify environmental stewardship in capitalist terms but, at this point, we’ll have to take what we can get. In terms of conservation, rewilding is a good start, but it’s critical that we not allow its philosophy to underpin our understanding of what a green future will look like.

To achieve the interpenetrating goals of mainstream climate consciousness and a net-zero society, it will be necessary to entirely reformulate the relationship between human beings and the so-called ‘wild.’ The Western impulse to fall back on the human/nature binary must be overcome. While rewilding emphatically separates human activity from natural landscapes to allow it to recover and – in some cases – thrive, the planet will only survive if and when we begin to think of ourselves as inescapably part of nature, so much so that we would never feel the need to ‘rediscover’ as eco-tourists in the first place.

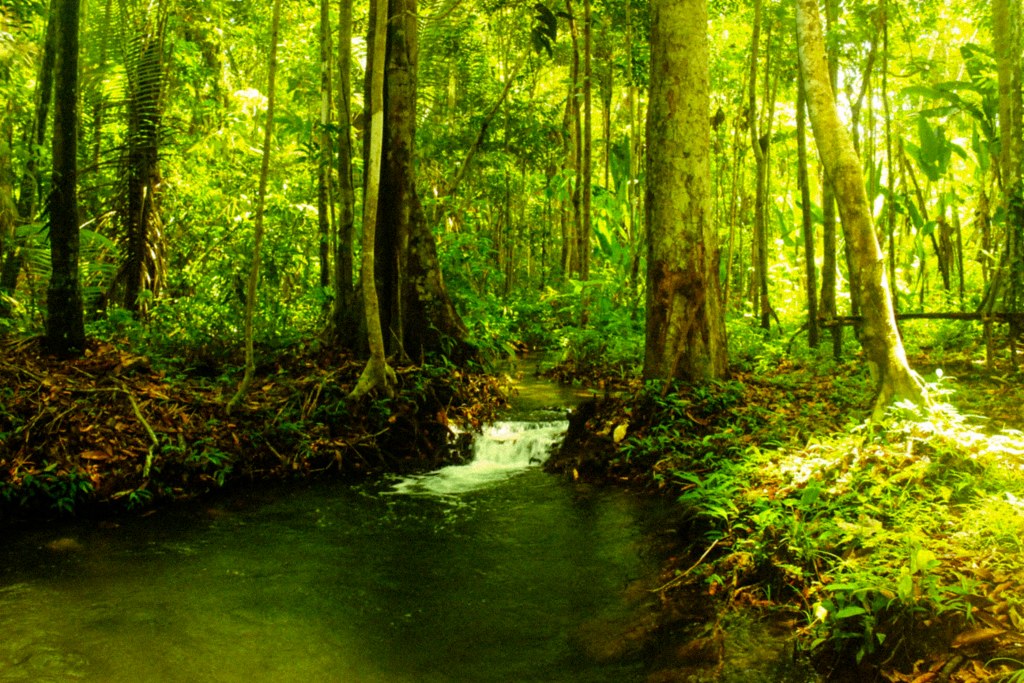

Photo by Damir Babacic