- About

- Topics

- Picks

- Audio

- Story

- In-Depth

- Opinion

- News

- Donate

- Signup for our newsletterOur Editors' Best Picks.Send

Read, Debate: Engage.

| topic: | Poverty |

|---|---|

| located: | United Kingdom |

| editor: | Gurmeet Singh |

The ongoing global pandemic is a peak-time for unpredictable news. Hardly a day goes by without something downright zany appearing in the headlines. It’s made it difficult to take everyday stories seriously, but we should try to keep their importance in mind.

Errol Graham, a 57-year old man died in his home in Nottingham in June 2018, after having his benefit payments cut. The payments were cut due to his failure to attend a work assessment meeting with the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP). Graham suffered from extreme social anxiety and cut himself off from his friends and family shortly thereafter. When he was found dead in his flat, it was concluded that he died of starvation. He weighed just over 28Kg.

His family are now taking legal action against the DWP, arguing that a man who was known to be extremely vulnerable, should never have had his payments cut.

The Guardian writes:

“Graham’s family is seeking a judicial review of the DWP’s safeguarding process system, saying he would be alive today if officials had checked properly on his health and wellbeing before automatically revoking his benefits for failing to attend a medical assessment, leaving him without income.

Despite knowing Graham’s long medical history of mental illness and failing to speak to him, the DWP told his inquest it had followed its safeguarding process correctly and that while it had unfortunate consequences, revoking Graham’s benefits was 'the right decision … for us to have made'.”

After his death, two of Mr. Graham’s teeth were found, and also a pair of pliers. It has been suggested that he pulled his own teeth out: a clear sign of mental health deterioration.

Writing in the Disability News Service in January 2020, John Pring points to the coroner’s report, which brings up vital questions about the U.K.’s welfare system, and its poor design:

“The assistant coroner said: 'There simply is no sufficient evidence as to how he was functioning, however, it is likely that his mental health was poor at this time – he does not appear to be having contact with other people, and he did not seek help from his GP or support agencies as he had done previously.”

She concluded in the narrative verdict, delivered last June, that the “safety net that should surround vulnerable people like Errol in our society had holes within it.”

She added that, “He needed the DWP to obtain more evidence [from his GP] at the time his ESA was stopped, to make a more informed decision about him, particularly following the failed safeguarding visits.”

In other words, the system only works if people themselves are able and willing to complete all the necessary bureaucratic steps to prove their physical, mental or economic situations. However, if a person is unable to complete those steps (say, due to extreme social anxiety), the system itself will not seek to fill in gaps of information. Instead, it will simply make a judgement about the person’s welfare claim.

His Daughter-in-Law, Alison Turner, told the BBC: "It is heartbreaking, horrific, for someone to die like that. The failure he suffered, he didn't deserve it. It is shocking. The system is not fit for purpose. He was without money for six to eight months. Errol could not physically bring himself to talk to strangers or ask for that level of help and if he hadn't have lost it he would still be here today."

The pandemic will continue to put pressure on the government and all social institutions, and it is unlikely that wholesale positive changes will be made to the systems soon. However, if we want to build a more humane society, we will have to be more creative and generous with respect to how our institutions treat every person.

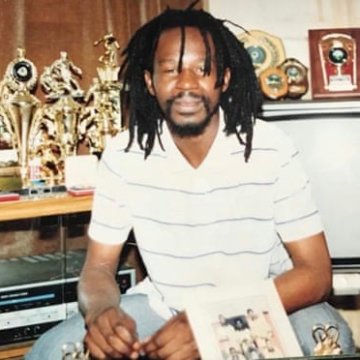

Image: Errol Graham weighed just 28kg when he was found dead at home by bailiffs in June 2018.