- About

- Topics

- Picks

- Audio

- Story

- In-Depth

- Opinion

- News

- Donate

- Signup for our newsletterOur Editors' Best Picks.Send

Read, Debate: Engage.

| topic: | Child rights |

|---|---|

| tags: | #child rights, #food security, #poverty, #education |

| located: | Ghana |

| by: | Charles E. Owubah |

Disclaimer: The views expressed in the article belong to the author and do not necessarily represent the position of FairPlanet.

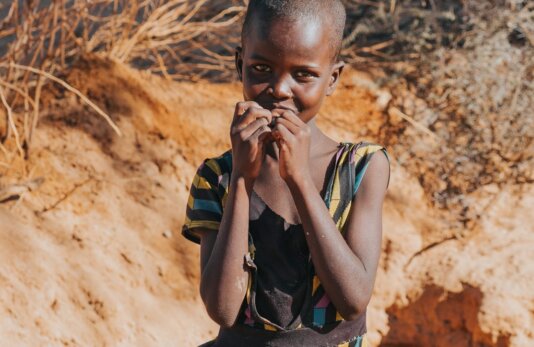

Growing up the son of farmers in Ghana, I understand the pain of going to bed hungry. Every year, for the months between planting and harvesting, we endured the "hunger season," when no meal was certain. Life was difficult, but we got by with help from our extended family and community.

Despite the hardship, I was fortunate enough to attend school. School didn’t excuse me from daily tasks. I would wake up at dawn and walk a mile to a stream to gather a bucket of water, carrying it home on my head. After making the trip several times, nearly six miles each day, I would bathe near the same stream and then go to school.

The belief that education could elevate my quality of life kept me going. Education fueled my dreams, a spark that would carry me around the world and toward my ambitions.

But school is harder when the body’s most fundamental needs, like food or water, are unmet. I was occasionally distracted by hunger. For some, malnutrition can stunt cognitive development and make learning nearly impossible. Opportunity begins where hunger ends.

14 June is the International Day of the African Child, a reminder of the millions of young people who aren’t getting a good start in life. The observance began as a commemoration of 1976 protests for equity in education in Soweto, South Africa. It has evolved to a broader focus on the opportunities and challenges to fully realising the rights of children in Africa.

According to the recently released Global Report on Food Crises, the three countries with the largest number of people facing acute food insecurity are on the African continent: the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Nigeria and Sudan. In all three countries and other hunger hot spots, conflict is exacerbating the hunger crisis and violating child rights.

In the DRC, for example, conflict has left nearly 7 million people internally displaced, making it the second-largest crisis of this kind anywhere in the world. Hundreds of thousands are hungry and need immediate humanitarian assistance. Since January’s upsurge in violence, Action Against Hunger health facilities in the region have admitted four times the number of severely malnourished children – all under five years old.

Similarly, this past April marked the first anniversary of the conflict in Sudan and one of the largest humanitarian crises in the world. Nearly 18 million people, or one in three Sudanese, face high levels of acute food insecurity. Conflict and hunger have forced 8.2 million people from their homes. The most vulnerable bear the brunt of the conflict, with 700,000 children under age five suffering from severe acute malnutrition, the most deadly form of hunger.

While the context in Nigeria is different, 1.74 million children face malnutrition amid growing inflation, as over 95 million families live on about USD 1.90 a day. This has a tremendous impact on kids’ ability to learn and grow. Food insecurity in children has been linked to developmental delays, including social and behavioral stunting, cognitive issues, and poor physical health.

Addressing hunger is not only a moral issue, it is an economic issue, too. Over the medium term, nearly two in three new workers globally will come from India and sub-Saharan Africa. Over the long term, Africa is the only region projected to enjoy strong population growth, which can provide a global demographic dividend—but only if we help children realise their potential.

Addressing hunger is a wise place to start. A 2022 study showed that every $1 invested in preventing chronic malnutrition in children can result in gains from $2 to $81 annually. Unfortunately, the world isn’t acting on the data.

According to the 2024 Hunger Funding Gap, only 35 per cent of appeals from countries dealing with crisis levels of hunger were satisfied in 2023, resulting in a hunger funding gap of 65 per cent, up 23 per cent from the prior year. Africa not only has the world’s youngest population, it has the highest hunger rates, with nine out of 10 children not receiving even the minimum acceptable diet, according to the World Health Organization.

Stunting in Africa’s children - or any child, anywhere - ultimately will stunt our world. But there is hope.

In South Africa, the Soweto protests were a turning point in the fight for equal opportunity. The demonstrations were seen across the globe and the world began to respond. The status quo is difficult to change, but awareness and action can make a difference. Progress can be achieved, both for individuals like me and for countries as a whole.

The world has more than enough resources to end hunger. I look forward to one day marking the International Day of the African Child with a celebration that every young person has enough high-quality food to eat and the ability to learn and dream as I once did.

Until then, we must prioritise food security so that every child has a chance to fulfill their highest potential.

Dr Charles E. Owubah is the CEO of Action Against Hunger.

Image by Tucker Tangeman.