- About

- Topics

- Picks

- Audio

- Story

- In-Depth

- Opinion

- News

- Donate

-

Signup for our newsletterOur Editors' Best Picks.Send

Read, Debate: Engage.

| July 25, 2014 | |

|---|---|

| topic: | Discrimination |

| tags: | #Albino, #Cluji, #East Africa, #London EEFF, #Noaz Deshe, #organ trafficking, #Ryan Gosling, #San Francisco Film Festival, #White Shadow |

| located: | Kenya, Mozambique, Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda |

| by: | Marc Hairapetian |

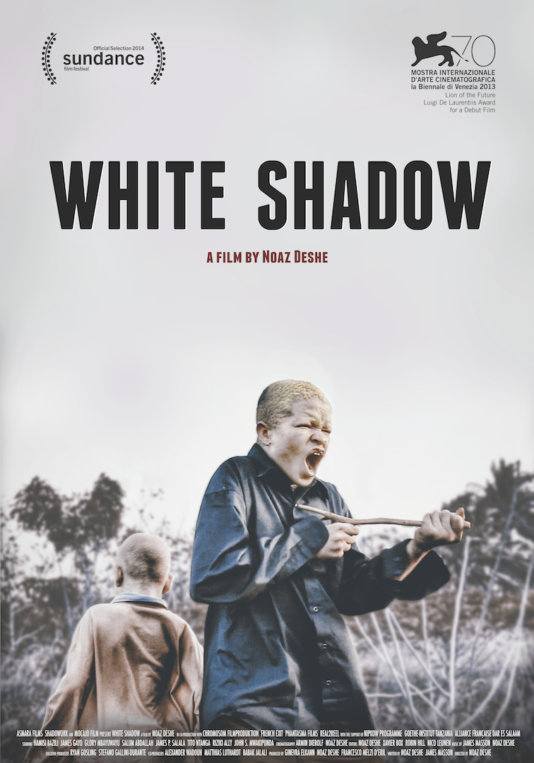

Shot like a documentary that moves between realism and surrealism this outstanding black magic thriller is based on a true story. „White Shadow“ was shown at several international film festivals (2014 in Sundance, San Fransisco, London EEFF, Cluij) and in 2013 director Noaz Deshe won the Luigi De Laurentiis Lion Of The Future Award in the Venice Film Festival for it.

In this FairPlanet interview, film critic Marc Hairapetian talks with Noaz Deshe about corruption, human rights and filmmaking.

FairPlanet: How did you come to the subject of Albino hunting in East Africa?

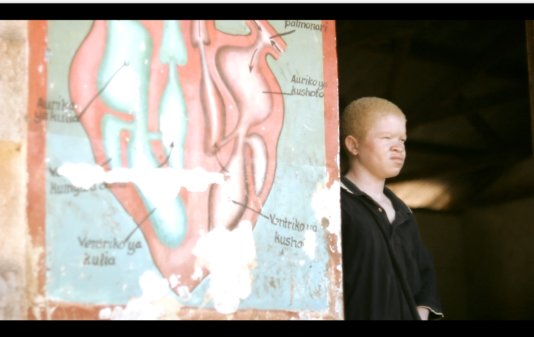

Noaz Deshe: „White Shadow“ is not entirely about the prosecution of albinos. It is mainly a story devoted to the experience of a character within that construct – Alias, a 14-year- old boy who is an Albino with all his problems, difficulties and mostly the feeling of being hunted. The subject or the whole story could be centuries old, the persecution of the "Other" fuelled by local spiritual leaders with invented narratives of super natural powers is an old tale. Yet in the East, South and West Africa today albinos are still being hunted, mainly far away from the main cities, in the rural areas. There have been about 131 recent killings and hundreds more attacks that result in mutilation, violence and endless psychological and existential damage.

There are 150,000 albinos in Tanzania. The outlawed Witch Doctors have created a business of organ trafficking around the belief that the different body parts of albinos have special magical powers: A heart will win you love, if you throw a leg into a diamond mine you will find more diamonds, tie their hair to the fishing net and your catch will be plentiful. The killers cut and hack the victims, then bring the body parts to the witch doctor who prepares potions from it and sells the prized goods to „honorary“ men who pay thousands of US dollars for it.

In 2010 a friend of mine, Matthias Luthardt, who was later a co-producer on „White Shadow“, invited me to join him to teach a short film course in Tanzania’s seat of government Dar es Salaam. The Goethe Institute Tanzania and Alliance Francaise were hosting us, and the objective was to make a short film with a group of approx. 40 local talents.

Naturally I wanted to find out more about the place we will be teaching, so I began reading about Dar es Salaam and local history. That night, very quickly I stumbled into a BBC report by Vicky Ntema, a very brave Tanzanian reporter who caught a witch doctor on a secret camera trying to sell albino body parts. She won a Courage in Journalism Award from the International Women’s Media Foundation for it. This immediately lit a fire in me and, as if possessed, I began consuming all possible info about the subject. By the morning the whole film manifested as if in a dream. It was clear it will be called White Shadow and the lead boy Alias will be on the run. Almost the whole story was on the page. I called my friend Mathias and said "We will go and teach and whomever is good in the course and wishes to stay with us, we will train as a professional crew, because we are making this film called White Shadow and this is what it is about..."

The guiding principal was that if we work with local collaborators as a local production team and keep the entire production as a local reaction to the subject we would be able to facilitate something that is already waiting to be told.

Together we studied all sources of local news, myths and customs, we read and translated private blogs and started calling people for witness accounts.

From there the idea for the film was born and we met many collaborators through the initial teaching course and workshop.

You know when you have an idea it dictates the way it should come to life. You are an employee of the idea. There was no question for me – the film had to be made.

You said that „honorary“ people who believe in witchcraft pay a „good price“ for the body parts of the hunted albinos. How much do they pay?

It depends on the different body parts but they go for between 700 and 50,000 dollars.

Was it difficult to find the cast?

Yes and no. We casted a lot on the street. For example Hashim Rubanza, my casting partner, and I walked into a fish market and watched the people going about their business, we identified the boss, he was sitting on bar stool surrounded by many very hardened fishermen and his role was to approve and name the prices of their fish. He had such show in how he was controlling the crowd around him. He was a natural performer. We asked him to come and audition for the one of the killers and he is in the film.

To compare it with other countries in Africa, Tanzania is a peaceful place. The regime is stable. Before they had a good connection to Russia and preferred socialism. But in their culture is a closed tradition to witchcraft. Not all of the witch doctors are bad. Some of them try to help sick people with alternative medicine. Officially, albino hunting started ten years ago but if you ask in Dar people will say it's older then the news. In recent reports we learned that first they robbed the graves and then later they started to kill people. I did not mention Tanzania in the film the story is relevant to Mozambique, Kenya, Uganda, Nigeria and South Africa. It is a regional and fictional story based on real facts. What the people play in the film is very close to their own lives. The bad guy in the movie is in real life the most feared police officer in the city. His job is to torture people for confessions. The amazing Hamisi Bazili who is acting as the protagonist Alias has a very similar emotional baggage to the character he plays. In real life he had to escape a village to be safe in the big city. It was really a gift to find him! When he was shooting with us he was 15, now he is 18 and wants to study.

Are you still in contact with him?

I am testing his English often on Skype. When we won a prize I sent him some of the prize money for his education. He recently flew with James Gayo who plays his uncle in the film to Detroit to show the film in the Michigan Cinetopia film festival and they both did a great discussion after the film. He is a natural entertainer and the crowd loved him.

Like the young Stanley Kubrick in 1953 with „Fear and Desire“ you were not just directing „White Shadow“. You worked on it as cinematographer – and more than Kubrick – also on the soundtrack. Was it not sometimes too much for you?

I am by far without his abilities. When it comes to this film it's a practical matter of what problems need to be solved. I [previously] made music for a few films, like in 2009 for the Iranian film „Frontier Blues“. It is a beautiful original film by Babak Jalali and now played in the Istanbul Museum of Modern Art. What an honor to be part of that. I also worked as a cinematographer for other directors. With „White Shadow“ it is the first time I was able to do everything under one umbrella. I worked with a very small team. In the beginning we were just two staff members, later we were four, but we had this energy to do it. We started without a financier. We filmed some stuff very early and sent it to the producers we believed in. Ginevra Elkan said she would produce it with Asmara Films. Then we got some money to realize it. When you have just a little money it doesn’t pollute your intimacy with the subjects.

Hollywood star Ryan Gosling is named as executive producer. Why did he not act in it with a small part, even though you wanted to work with non- professional actors? Maybe it could help the film because he has a big name.

He saw the film when it was almost finished. And Ryan, who is very outspoken, found it important to support it. Together we decided that when he puts just his name on it, it would be enough. It will open doors to being noticed. For me he is a wonderful artist of many disciplines, also a fantastic director. His name stands for independent quality within the studio system, gives [the film] extra credibility or opens another road for it.

Let’s talk again about the money for the film. How high was your budget?

I don’t want to give a sum but it was very low, even [though] we paid everybody. There are two thousand extras in the film. Some of the film feels or looks documentary-like. But thereare no documentary moments in the film. First we had to knock on every door and call for a village meeting and then convince everyone to participate. We offered a weeks' pay for a day of work, plus breakfast, lunch and dinner. We bought groceries so all the mamas in the village cooked and the film belonged to all of us in that sense. Especially when mamas were cooking, everyone wanted it to happen.

Making a film requires discipline. Was this a problem for the non-professional East Africans actors?

It was very, very hard to schedule, but once you begin shooting the level of commitment is beyond anything I have ever experienced. They are immediately in the moment in the role and are natural performers.

Even you said Tanzania is more peaceful then other African states. Was it not sometimes dangerous to shoot the film, especially because it deals with the subject of albino hunting and witchcraft?

You have to avoid danger. First, you have to convince people of all denominations that it is their film and they can collaborate creatively, they will have a voice. If you cast a gang leader and explain the importance of the film, the seriousness of taking on a creative role, then you have his gang as well. [Then] they will protect and not disturb the shooting of your film. The worst thing in Tanzania is to call somebody a „thief“ because they will immediately stop everything they are doing to beat and stone the accused. And be sure: In the rural areas the police will not intervene.

Second: You have to get the permit from the minister and you have to pay the minster directly.

Third: You have to get the permit of the police commissioner that allows you to shoot with other police officers. That protects you. It is necessary that the regime is behind you. You cast police officers but also the murderers who [are now] out of jail. You cast religious persons who believe in witchcraft. You cast albinos. Then you bring them all together in a creative process. And nobody wants to kill you anymore because everything [is] balanced out from itself. It is now also their film!

But recognize: You must always be very honest when you come there as a filmmaker. You never come there as a colonialist. I shot the first half of the film mostly alone it was very hard. I approached a cinematographer from Berlin. His name is Armin Dierolf. He had a very natural integration in Tanzania and then all was working much easier than before. So we had, all together, great teamwork.

So you had to make arrangements with a corrupt regime in order to make your film?

We have to be careful about blaming regimes. Almost all humans and particularly in power hierarchies are corruptible. Corruption is a systemic ingredient of every regime. All regimes all over the world are battling corruption – more or less.

Tanzania is a lot less inflicted then the USA or Germany, simply because there is no smoke screen of manufacturing democracies on the flag. I have a lot of respect for the fact that it is a peaceful country unlike many of its neighbors, that is what made it possible to shoot the film there and we enjoyed making the film without almost any interruption from local authorities as they felt it is important. Yes here and there a cop or a secret police officer would decide it's their ticket of daily fortune but thankfully the police commissioner gave us a permit to film other police officers and it was great deterrent. Further more the film was casted in a way that in incorporates all factions, the police, the gangs, the villagers, the lawful witches and so forth. It was everyone’s film so it would be harder to go against it.

I got word today that the prime minister of Tanzania will support the film and allow us to show it in the country. He felt that the international awareness and recognition justifies letting the film have a life in his country.

Remember: You have to separate your own personality from when you were brain washed by mediocre history books as a child. How much pollution have you consumed from your own government when you were growing up? Some classical clichés about Africa may be true but, for example, we grew up with the idea that Sweden is the bastion of freedom and equality, but Sweden is one of the biggest weapon dealers in the world – [and so is] Germany. What is true? What is wrong? You ask anyone what is the charge against Julian Assange and 90% will say "rape". It’s false, it's Western media distortion, a dirty trick of his political enemies in the „civilized“ western world.

The United States of America likes to play world police, but what their governments did until today - amongst its many humanitarian and war crimes - is being the only nation that saw fit to drop an atomic bomb on an already defeated nation in the name of it's economically driven "democracy". If we compare it, Tanzania is an infant and „honest“ regime. Tanzania is a very stable country and not violent at all.

You said in the beginning of our interview „White Shadow“ is not a film about the hunting of the albinos, it is about one albino character. But when we see the cruelty and injustice in it we feel hurt and want to protest against this crime, against the abuse of human rights. The general question is: Can a film like yours change something for albino people? Can art change human and political injustice?

There is a movie I really love. It is a Roberto Rossellini film from the end of the Second World War: „Germania Anno Zero“ (Germany Year Zero“). What a brave film! To shoot in a country which everybody was demonizing [across] the rest of the world. I am sure it opened a door for many to heal and return to see each other as humans. It is not the goal of every film neither should it be.

I love „I am Cuba“, directed by Mikhail Kalatozov, or „The Battle of Algiers“ directed by Gillo Pontecorvo, too. By mentioning those we don’t want to compare. These are historical seminal works of art that stand the test of time. They are there on the shelf to look up to. It is enough that they make you want to make!

To me, it is important that the Tanzanian and East African people have a dialogue and are able to respond to „White Shadow“. Until now the reactions have been very positive there, and we have been approached by several teachers that want to show the film to students. The screenings there gave us a lot of confidence to continue showing it.

Furthermore our collaborators have all understood that making a film is mostly insisting and insisting and we have given equipment and support to some of our team mates there, so they can pursue their own creative collaborations as filmmakers. They will make challenging films.

International film festival recognition is helpful. This acknowledgement from outside helps propel awareness internally and since the film is accepted internationally, it’s a collective source of accomplishment.

You can ask why I have to do it: because I am a foreigner to the people of Tanzania.

There is a fundamental connection between humans that you can identify within these extreme situations, it surfaces faster out, no matter where you are from and what you are. If an idea arrives it is something you cannot ignore. It is above all categorizations and you must follow it. The beauty of movies is very much, for me, about that link that crosses all national and mental borders, languages. Just like music.

Regardless of our national indoctrinations we all crave the same point of contact the same mutual understandings. It proves again and again we have a key to render all war politics as irrelevant. We are all equally wise and silly. We all meet in dreams. As a worker I don't have answers to anything, so your duty is to keep asking questions as many questions you feel strongly about, and keep questioning the questions. Why not?

Marc Hairapetian is since his 16th living year editor of the film-, theatre-, music-, literature and audio drama magazine SPIRIT - EIN LÄCHELN IM STURM www.spirit-ein-laecheln-im-sturm.de which is celebrating its 30th anniversary in August 2014. He is also working for magazines like Spiegel Online or Newspapers like Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung.

The interview with Noaz Deshe he was doing exclusively for FairPlanet.

By copying the embed code below, you agree to adhere to our republishing guidelines.