- About

- Topics

- Picks

- Audio

- Story

- In-Depth

- Opinion

- News

- Donate

- Signup for our newsletterOur Editors' Best Picks.Send

Read, Debate: Engage.

| June 10, 2022 | |

|---|---|

| topic: | Arts |

| tags: | #Pakistan, #Indus River, #art, #water, #conservation, #mining |

| located: | Pakistan |

| by: | Samia Qaiyum |

To say the Indus River is sacred would be an understatement. Not only is its surrounding landscape dominated by mosques, temples and shrines of varying sizes, but it also forms the backbone of agriculture and food production in Pakistan, making it of utmost importance to the economy.

But between Kashmir's melting glaciers and irrigation and hydroelectric projects draining its flow, the future of Pakistan's primary freshwater source - particularly downstream - is precarious. And because corruption remains rampant, so does water theft and declining water distribution.

Incidentally, the Indus River originates in Tibet, crosses Indian-controlled Kashmir, and flows through Pakistan before emptying into the Arabian Sea near the port city of Karachi. It is here that Zulfikar Ali Bhutto resides.

Of mixed Pakistani and Lebanese descent, the artist is the scion of a political dynasty; he is the nephew of former prime minister Benazir Bhutto and grandson (and namesake) of former president and prime minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. Political aspirations, however, don't make an appearance in his journey to date.

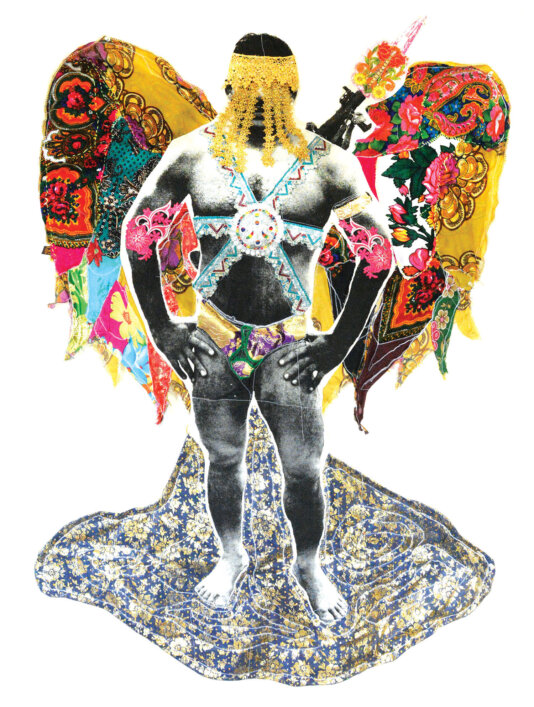

After a stint in San Francisco, where his alter ego Faluda Islam challenged the narrative that Islam and queerness are oppositional through performance art, Bhutto returned to his hometown and continued his many creative endeavours.

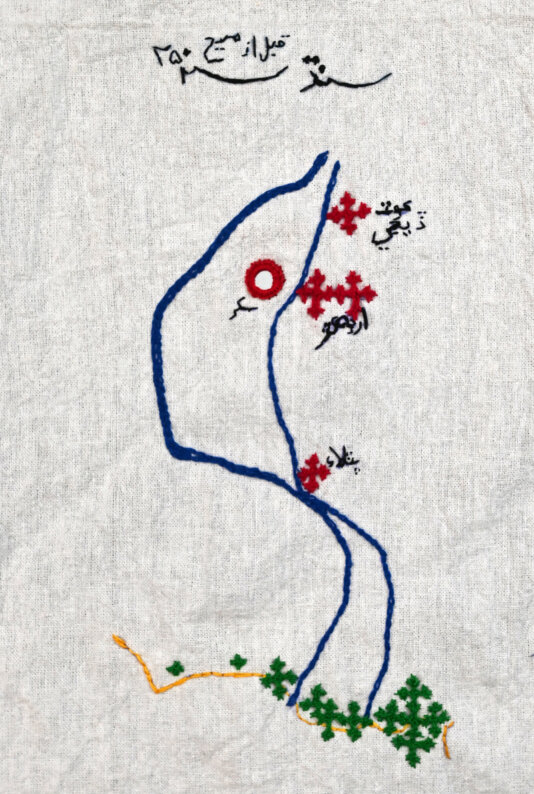

While his work spans a multitude of mediums, the artist has most recently turned his efforts to wildlife advocacy with the help of textile art. Entitled Bulhan Nameh, which translates to 'dolphin diaries', his new series explores a 10km stretch of the Indus River that is punctuated by the British-era Sukkur Barrage at one end and the dilapidated island shrine of river saint Khwaja Khizr at the other.

Bhutto's Bulhan (the Sindhi word for the Indus River Dolphin) nameh (the Urdu and Sindhi word for diary) is a deeply personal diary written through textile and printmaking. As wildlife, history and spirituality collide with colonialism, capitalism and feudalism in this vicinity, Bhutto is pairing cyanotypes, analogue photographs and archive with khaddar fabric and traditional Sindhi embroidery as a way to root his project within its current cultural landscape as well as with memory, nostalgia and a sense of loss.

Through his research, Bhutto hopes to re-mystify the river and, in the process, allow audiences to reimagine it as a living and dynamic entity rather than simply an exploitable resource.

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto spoke to FairPlanet over Zoom following the release of a special Dastaangoi stencil collection that he co-designed to raise money for WWF-Pakistan's initiatives to study and conserve the Indus River dolphin.

FairPlanet: How has your background and upbringing shaped your desire to highlight environmental issues through creative mediums?

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto: I wouldn't say this project represents a huge shift, but aesthetically it is a definite shift from my previous body of work Tomorrow We Inherit the Earth, which I started while I was away in the US and I'm currently wrapping up. And that was about a sci-fi Muslim's future, and it was very much rooted in the political history of South Asia and the Middle East; but it was not about the present, it was not about what is happening today.

It's very much about what happened yesterday and what could happen tomorrow. As for creativity? It's just something that comes naturally to me, it's just how I express myself. I think artists are very obsessive people; we have obsessions that we can't let go of until we've seen them expressed - and that is the case for all my projects, I think.

With this particular one, I actually sort of started it when I was 15, in 2005, when I was still living in Pakistan and hell-bent on being an environmentalist. I loved art even then, but for me, environmentalism was the thing to do.

Your Bulhan Nameh series is rooted in the Indus River. Where does your personal attachment to this body of water stem from?

I started volunteering for WWF, and I was particularly interested in the Indus River dolphin at that time. I had never seen one, and so many people have never seen one, dismissing them as extinct, like they were gone, they didn't exist anymore.

Through my work with WWF, I was put in touch with a gentleman who is no longer with us, Dr. Hussain Bakhsh Bhagat. He was the head of Sindh Wildlife Department for a number of years, and he was very dedicated to the cause - especially of the Indus River dolphin - and he took me in the middle of the city of Sukkur on a boat trip and, within minutes, I saw my first dolphin. And it was such an exquisite experience. It was like seeing a unicorn. That was in 2005.

The following year, he invited me on a dolphin rescue mission as they get stranded in canals. In Pakistan, they flood the canals during the rainy season, and then the canals dry up during the dry season, so dolphins can die if they are left in there.

One of the big initiatives of the Sindh Wildlife Department is these yearly rescues, so I participated in one. I saw a small, four-foot-long young male dolphin, I still remember, and it was such an incredible experience. I mean, a unicorn is still a far-out idea. It looked more like an alien up close because they have these huge bulbous heads and long, long jaws. And they are somewhat prehistoric, they are the ancestors to the modern dolphin, which is why they look a little different.

As time passed, I left the country for school and eventually decided to live in the US for a few years. Admittedly, my connection to Pakistan was still there, but it wasn’t strong enough that I could continue this passion, and the environment that I was in was a little different, and so my mind was elsewhere.

When I returned in October 2020, however, it just made sense to continue looking not only at the Indus River dolphin in relation to its environment, but also the dolphin and the river in relation to the very diverse spiritual practices around it - and this is especially poignant in Sukkur, which my project has been heavily focused on.

Regarding the family connection, it's never something that I centre in my work, though I understand that my voice carries a different weight to other artists' voices. And in the case of this project, I am making use of that because this is an urgent matter.

For me, what's interesting is that the Indus River dolphin was declared a protected species and hunting was banned in 1972. And then in 1974, the Indus Dolphin Reserve was created between the Sukkur and Guddu Barrages, and my grandfather had a personal interest in the dolphin as well. He was a big part of why both the Sindh Wildlife Department and Indus Dolphin Reserve exist. That's why I try to emphasise that this is a legacy, but of course, it's not why I'm involved - I just think it's a good coincidence.

More broadly, what do you want the world to know about the river's cultural and spiritual significance?

I was speaking with marine biologist Dr. Gill Braulik - she's been coming to Pakistan for the dolphin survey for decades - who was saying that the Indus River was part of one giant river system that is 40 million years old. It's as old as the Himalayas.

And then, eventually, these river systems separated; the Indus separated from the Ganges around 600,000 years ago. So, if you can imagine for 600,000 years, humanity and wildlife have depended on the Indus River; some species depended exclusively on this river, one of them being the dolphin.

And it's very likely that the dolphin itself is also around 30 million years old, making it one of the oldest cetacean species.

Regarding the spiritual history of the river, something that old creates culture; so I think as time has moved on, the evidence that we have of a deep cultural and spiritual connection of Pakistani people to the river is most clear in the province of Sindh and in the city of Sukkur.

I'll give you an example: within a 5km length, perhaps even less, you have Sadhu Bel, an old Hindu temple that is still actively used, in the middle of the river itself. Then, slightly further upstream, you have Bukkur Fort, which is an Arab fort - and that's on an island as well. And slightly further upstream of that, you have the shine of Khwaja Khizr, also on an island.

Khwaja Khizr is a prophet mentioned in the Quran. He's an ever-living prophet who lives in water, so he has a throne on an island and Hindus also worship him, so there's a Hindu temple across from the island called Zinda Pir. And then across the river from that temple is Satiyan Jo Aastan, a shrine dedicated to seven sisters who were about to be married off to this tyrant and, instead of suffering a life of indignity, they threw themselves into the river and are buried at the point.

A lot of people think the 'Satiyan' is in reference to the seven sisters [saat in Urdu means seven], but it's actually 'Sati' that comes from the Hindu practice of widows committing suicide essentially on their husband's funeral pyre, while the word sati itself means pure.

It's problematic through a contemporary and progressive lens, but through the lens of spiritual mingling, the fact that a Muslim shrine has a Hindu name and contains Hindu motifs all around is very interesting, so you have this incredible mixing of religions.

What can you tell us about the river's current state of fragility and how it has impacted life around it?

Well, in the middle of all these shrines and temples that are on the river, you have these very aggressive colonial and post-colonial structures, namely the Sukkur Barrage and Lansdowne Bridge. And then there's Ayub Bridge, funded by the IMF, which also funded various other dams and barrages that have actually led to the severe water shortage issues that we're facing today.

Downstream of Sukkur Barrage is the end of this sort of magical area, which is also where hundreds of dolphins swim between these monuments. This is the best place to see dolphins in all of Pakistan. And right after this barrage, the river becomes a very sad, sad place.

Just from Sukkur Barrage alone, the canal system is 50 million miles in total, so if you can imagine that's billions of gallons of water that are just being pulled from the river, so after this, the river becomes very small, very thin. And then by the time it reaches Kotri Barrage, a few hundred kilometres downstream, the river runs dry for most of the year.

And now the government has just finished building one dam as far as I know and is in the process of building five more. And this year, Sindh faced a really terrible water crisis, the canals could not be filled to full capacity, and several cities that never have water issues don't have drinking water - and it's because there's so much water hoarding happening upstream.

Pakistan is so anxious about water problems that it's only hoarding the water upstream and not considering downstream, which is perhaps the most biodiverse in the country. So as our water crisis grows in intensity, it poses a larger and larger threat to our river dolphin population, which has both grown and stabilised over the years.

It's actually a very healthy population, but with these water issues, Sindh will suffer the most. And the less water we have, the first indication will be a decrease in the health and the population of the river dolphin, so they become the proverbial canary in the coal mine. And then our fate - the human and the dolphin population - would become ever more intimately bonded.

Pakistan is ranked amongst the top 10 countries most vulnerable to climate change. What can you tell us aboutany ongoing green initiatives and your own involvement?

I recently joined a dolphin survey - we traversed a huge chunk of the river - and I was with these people from the Punjab Wildlife Department, which is at the forefront of the country's Ten Billion Tree Tsunami initiative.

Pakistan has had success with this, and has had more success than most countries that have started tree-planting initiatives, as far as I'm aware, in the sense that there has been actual research into native tree populations.

The focus is on Northern Pakistan, where the water hoarding is happening. There is also a mangrove plantation scheme happening, which is the largest of its kind. And these are all positive things. I think any sort of local or indigenous population would be invested because if you're living on the mangroves, you're invested in them because they supply nurseries for fish, they protect against storms, they give you fuel, they give you fodder - it's a whole economy that thrives off them.

Can someone like me help highlight such initiatives? Sure, I do think that my voice is probably more useful here than it was when I lived in the US. I'm very active on Twitter, talking about the environment, about wildlife, about the Indus River particularly and trying to link it to the human population because there's this unfortunate association between environmentalism and a privileged way of thinking - prioritising forests and animals essentially.

I mean, what does the army or government care when you're talking about these 'abstract' things such as dolphins, so you make it about humans, right? It is about the human connection, too. I'm trying not to mince my words here, I'm always willing to lend my voice to the environment, and my focus is the dolphin and the river, but of course it extends throughout the whole system.

Unfortunately, though, what we face is a political system that is not only somewhat unstable, but also rigged. For example, Imran Khan started this initiative - and I'm not an Imran Khan supporter - but the question is what happens when he is replaced? Will the next government sustain this initiative? Will the funding remain the same? And, ultimately, the deciding factor in all of this is the army. The army in Pakistan has huge control over everything - be it environmental, social, political. So in some way, it then becomes the job of the political system to convince the army of the importance of nature and wildlife.

What I'm trying to say is that I like to be involved and I can do all these things, but it's other people who decide how much water we get or how much water goes to the Department of Forest.

It's kind of ironic - we're doing a mangrove replanting mission and there's no water in the Indus River Delta, so there are so many cycles that we're not taking into consideration. The environmental stability is very, very political in Pakistan, and it's very close to those in power, so that's the only anxiety.

We must convince the people up there and, in some way, my family background starts becoming irrelevant because it's not the Pakistani people that I'm trying to convince; they understand the importance of sustainability to some degree, especially people who are farmers and fishermen. The rural population understands the urgency - it's the decision-makers whom we have to think about.

You've been vocal about the threats faced by the Mohana fishing community, addressing the fact that everyone from provincial governments to private entities are to blame. Can you share a little about the crisis and your support for the Save Manchar Lake movement?

The Mohana community isn't actually restricted to Manchar Lake - they're on the Indus River as well. What's interesting is that it used to be one of about 150 indigenous communities that lived on the Indus in boats - now they're one of the only ones left.

That tells you a lot about the quality of water in Pakistan and in Sindh as well as the security situation. The Indus River was a very peaceful, safe place until the 1980s, when the security situation became really, really terrible. The river became a hideout for dacoits who would often target the Mohana, so many of them moved to Punjab or completely gave up their way of life.

As for the Mohana on Manchar Lake, this is a community of about 80,000 people, or at least it was a few years ago. The lake itself is very big, but also very shallow. It naturally receives freshwater from rainfall or the surrounding hills or the Indus River as there's a stream that connects it.

But what's happened is that the government has created these two huge canal systems: Right Bank Outfall Drain and Left Bank Outfall Drain. And what they do is transport industrial, water-based waste all the way from Punjab, which is carried through Sindh and dumped into Manchar Lake - they chose one of the largest bird sanctuaries in Pakistan and one of the largest lakes in Asia to do this. Additionally, the government is not allowing water to go from the Indus into the lake anymore; they're using the freshwater for agriculture and mining.

The hills of Sindh are being mined excessively because they contain lime, which is used for cement, plaster, granite. And, of course, all these heavy industries also require water, so basically what's happening is that the lake is becoming increasingly saline and smaller and smaller.

And you don't have adequate input of freshwater, either. As a result, the effects of evaporation take hold, making pomfret one of the few types of fish that can survive - and it's not even a native species. Pomfret is a seawater fish that was only introduced when the lake started to become saline, so it's the only one that the Mohanas are now able to fish. It's not their traditional diet, either. And while there are still a lot of pelicans, the amount and types of birds has also decreased significantly.

And what about your personal role?

My support was one of those things that felt like the right thing to do, and people were wanting my voice. And of course, anyone who thinks that much of a lake should just evaporate into the wilderness through negligence is wrong. While I've had to put a pause on my efforts because of my current project, I am in touch with the Sindh Wildlife Department, but again, the problem goes back to the people who hold the power - they're the same people who control the valves that open water networks.

Water and power in Pakistan are one and the same. How do we convince the people in power to allow Machar Lake to have water? All of this goes back to the same issue, which is that the Indus River and other hydrological cycles and practices are not being allowed to do their natural thing.

It makes sense in some ways on a purely government level; if you're thinking as a civil servant or an army engineer or whatever, you're thinking, 'How do I store as much water as I can for this ever-growing population?' But the reality is that the Mohanas are people, too. All of those people living in small villages and towns on the Indus River Delta? They are people, too. And they've all been deprived of freshwater.

"Water and power in Pakistan are one and the same."

It's just so absurd, the kind of hyper anxiety around water and the climate crisis. I believe Pakistan used to be the home of the Karakoram Anomaly, with the glaciers of the mountain range increasing rather than decreasing - but that's changed. They are melting, they are shrinking, so it doesn't matter how much water they hoard in the north. Down the line, we're all in trouble. Now, I don't know who's going to fix the glaciers, but I certainly don't think that building more dams and barrages is the solution - Pakistan already has 150 dams and over 15 barrages. We don't need anymore.

What ultimately is the end goal of your Bulhan Nameh project as you continue work on this front?

I'm seeing where it takes me. Most projects of mine are of that type - I just see where the wind takes me, and I keep trying and trying and trying.

The aesthetics and mediums keep taking shape. I'm primarily a textile artist and, interestingly, textiles are very connected to water in many ways as well. I'm seeing where it goes, I've entered several collaborations already, and I've received some support from institutions within Pakistan - artistic and otherwise - to keep going.

Image by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto.

By copying the embed code below, you agree to adhere to our republishing guidelines.