- About

- Topics

- Picks

- Audio

- Story

- In-Depth

- Opinion

- News

- Donate

- Signup for our newsletterOur Editors' Best Picks.Send

Read, Debate: Engage.

| July 18, 2024 | |

|---|---|

| topic: | Refugees and Asylum |

| tags: | #Myanmar, #Thailand, #military coup, #education, #Mental health |

| located: | Myanmar, Thailand |

| by: | Anne Chan |

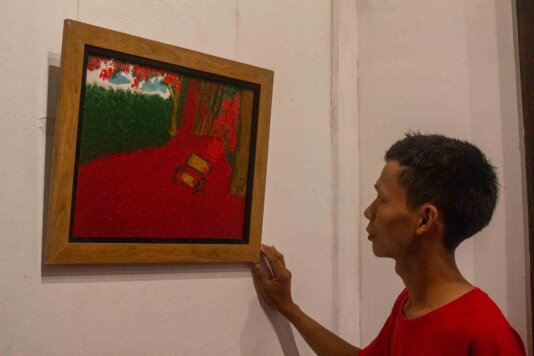

Thae Ko Ko, 22-year-old Burmese refugee in Mae Sot, had plans to enroll in university and build a future in Myanmar three years ago, but his life changed following the coup led by army chief Min Aung Hlaing on 1 February, 2021.

The military coup deposed the democratically elected government of Aung San Suu Kyi's party, the National League for Democracy, replacing it with a ruling military junta and plunging the country into a state of instability and violence.

Widespread public opposition to the military's forcible takeover and bloody crackdown on protesters has resulted in at least 5,000 deaths and more than 20,000 detentions, according to the Burmese advocacy group Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (AAPP).

In Thae Ko Ko's hometown of Bago, the military has killed at least 82 people during an anti-junta protest in 2021, according to AAPP. His friend, who had participated in a protest alongside him, was captured by the army following the crackdown.

Thae Ko Ko then fled to Mae Sot on Thailand's western edge, around 300 kilometers from his hometown. A barbed wire fence along the border between the Thai town and Myanmar's Myawaddy is all that separates the two nations.

Speaking with FairPlanet, Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (AAPP) stated that least 30,000 people have fled to the Thai border town of Mae Sot seeking safety since the 2021 military coup.

But Mae Sot has become an uneasy refuge for Burmese on the run. It is a town full of exiles planning revolution, awaiting asylum offers, constantly fearing spies and living in a state of almost constant despair.

"Since 2021 until now, I watch news every day," said Thae Ko Ko. "I see a lot of people are dying."

The national conscription imposed by Myanmar's military rulers since February this year has also dashed Thae Ko Ko's dream of returning to his hometown, as the conscription applies to all men between the ages of 18 and 35.

"I think military leaders are really foolish," shared Thae Ko Ko, who refused to fight against his own people. "We are staying in one country. Our citizens are the same, but we are killing each other in the same country. It's really awful."

Non-governmental organisations in Mae Sot have started offering free counselling services to assist Burmese refugees who have been grappling with persistent depression since the coup.

Among these organisations, AAPP has provided free counselling to more than 5,000 Burmese exiles and their family members who reside in Mae Sot.

Z, 56, is a core member of the AAPP responsible for the counseling service. He has chosen not to disclose his real name, as the military labeled AAPP an illegal group following the coup. The organisation aims to secure the unconditional release of all political prisoners in Myanmar.

Z was previously imprisoned from 1992 to 1998 on charges of undermining national security and involvement in an unlawful association. He fled to Thailand roughly 20 years ago.

Speaking to FairPlanet, Z clarified that he had never engaged in any acts of violence. Instead, he distributed leaflets and participated in peaceful protests against the military government and for democracy. He said he joined these demonstrations in the wake of the 1988 Uprising.

Even after his release from prison, Z continued to clandestinely engage in political activism. Fearing a potential return to prison, he decided to seek refuge in Thailand.

"As I am a former political prisoner, I think about how I can help or how I can contribute something to the community," Z said, stressing that mental health, although often neglected, is an essential aspect of overall human well-being.

"There are no mental health services in Burma. It's necessary for Burmese."

However, in life-or-death situations, mental health support may not be a priority for some refugees.

"It was very challenging because sometimes [the refugee client] doesn't have any food or money," said Z. "He would [say], 'yes, mental counselling is very helpful for me, but it can't stop hunger.'"

Thailand, which has already provided refuge to over 90,000 Burmese refugees since the mid-1980s, expects to accept 100,000 more refugees from Myanmar due to the ongoing conflict.

Z stated that since 2021, AAPP had been providing a one-time support of 5,000 Baht (USD 136) to each refugee household. But the scheme had to be suspended after assisting around 2,000 households due to insufficient funding and overwhelming demand.

At least 1,000 households are still waiting for support from AAPP.

Charity schools in Mae Sot are struggling to survive due to the influx of refugees, but some remain operational.

Pyo Khin Learning Center, established 25 years ago, is a charity school catering to Burmese refugees.

The centre comprises four basic indoor classrooms for junior students. In one classroom, around 30 junior pupils sit on mats, taking notes on plastic tables. Around 100 children share the other three classrooms, which have plastic chairs and wooden desks.

Older students have to attend classes outdoors, sheltered only by a metal covering that provides minimal protection from the elements.

To save on electricity, all students rely solely on natural sunlight to study, even though it is dim during the rainy season.

The roughly constructed classrooms manage to keep rainwater out, but puddles in the outdoor areas of the school have become breeding grounds for mosquitoes and flies.

Mai Mar Mar Yi, 55, is the second principal of the learning centre. This year, she said, they caters to around 200 students, up from 160 last year. The majority of these students come from Myawaddy, a crucial trading post in Myanmar where rebels have been fighting against the junta.

Eleven-year-old Than Than Myint, from Myawaddy, has been studying at the center for less than a year. She recalled her home being destroyed by shelling and bombing during the conflict. As a result, her family had no choice but to illegally cross the border in search of a new home in an unfamiliar place.

Despite the longing to return to a home that no longer exists, Than Than Myint remains resilient in adapting to her new life in Mae Sot.

"I like this school. The students are polite. Our religions are the same. We are like a family," Than Than Myint told FairPlanet. "I like studying English, because I want to visit different counties in the future."

Mai Mar Mar Yi said it has been difficult to sustain the centre's operations with only eight teachers, limited resources and dilapidated classrooms.

However, Mai Mar Mar Yi, who was a teacher in Yangon before escaping from Myanmar with her exiled relative, said she would continue to run the school and pursue her passion in this foreign land.

"Education is very important, because they can extend their own horizon to learn, to study and read; they can...," she paused, tears welling her eyes. "Otherwise, they would just work and not study."

Image by Anne Chan.

By copying the embed code below, you agree to adhere to our republishing guidelines.