- About

- Topics

- Picks

- Audio

- Story

- In-Depth

- Opinion

- News

- Donate

- Signup for our newsletterOur Editors' Best Picks.Send

Read, Debate: Engage.

| November 03, 2022 | |

|---|---|

| topic: | Climate action |

| tags: | #climate change, #climate action, #New Zealand, #indigenous peoples |

| located: | New Zealand |

| by: | Frank Odenthal |

Using a board game as a way to cultivate climate adaptation might seem like an unorthodox endeavour. Yet scientists call such games serious games, and Marae-opoly is one of them.

The game was designed by New Zealand‘s National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA) as a way to fuse traditional Māori knowledge and values with climate change data in order to help players brainstorm flood solutions and watch how the effects of their decisions evolve over time.

FairPlanet spoke to Dr Paula Blackett, one of the project’s lead scientists, about how Marae-opoly works, what it was designed to achieve and what role can board games play in increasing awareness of and resilience to climate change.

FairPlanet: What is the benefit of playing games to explain serious issues?

Dr Paula Blackett: There are a number of reasons for it. A game allows you to make a series of decisions over a period of time, feel the consequences of those choices and experience the benefits of these choices. Because none of it is real, it can be an experimental place where you can try strategies that perhaps you wouldn‘t have normally done.

So it‘s safe, it‘s experimental, but it is just real enough to be relevant. And in the case of Marae-opoly it was pretty real for the people of that particular place.

Could you give an overview of the setting of the board game?

Māori are the indigenous peoples of New Zealand, so for them there is a close connection with land, [which is] collectively owned. The tribal structure is complex: Iwi (tribe) is a large number of people. And within each Iwi there‘s a number of hapu (subtribes). Hapu tend to hold marae, which [is the Māori word for assembly]. It consists of a house where people can meet - we call it the Whare nui, like a space where people come together to talk and discuss and to make decisions. There is also usually a kitchen and a dining hall, and sometimes a place where people can sleep. It‘s quite a complex building. And within each hapu there is a series of whanau, like families. That‘s how the structure works.

Also, [throughout] the colonial history of New Zealand, a lot of land was taken from the Māori, and the land that was left, the spaces where a lot of these marae sit, are often in quite risky places. They might be on a flood plain, they might be close to the coast, so there‘s been a loss of land as part of that colonisation process. That‘s a difficult backdrop against which to make decisions.

So how did the decision making process evolve?

For the Māori, when it comes down to making decisions about marae and what to do, it‘s about the connection with that place, which runs very deep. There may be limited options of where else they could move to, and also the buildings themselves have a deep history. There‘s carvings on the front of the meeting house, [which were] built by their ancestors.

So it‘s a very thorough and painful and difficult conversation. And the games really allowed us to let people discuss and try different strategies.

And it was safe, nothing was moved, nothing was flooded in reality, but lots of things were tried. There was quite a deep division within the hapu as to whether to move or stay. That was quite deeply entrenched, so the discussions became a little bit heated, a little bit tense.

You introduced the game to the Māori community of the Tangoio near the city of Napier on the North Island of New Zealand. How easy was it to convince them to join the game?

It was part of a larger process. We worked with the hapu to put together a joint research bid. The purpose of that bid was to help the hapu to make a decision as to what they were going to do.

The first thing we had to do was to understand the aspirations that this particular community had. What was it that they wanted to achieve? And then we put that all together and looked at the area’s flood history: What happened, what damage did it cause, what did it look like? Then we looked at future possible flood risks with some modelling - which turned out to be relatively inconclusive. It was like: Well, it might flood really badly, but then again it might not… and that didn‘t really help us.

So then we moved onto the gaming phase. But because we had that previous relationship [...] it was pretty easy to convince people to give it a try, because they knew us; we talked and worked together [and] it was a co-developed process. They were partners.

“The game is just real enough to be relevant”

How does the game itself work?

Marae-opoly is not really like Monopoly. It‘s just a catchy name that we came up with.

Each player is given a map of the marae with the buildings on it and the river that flows through. And then they‘re given some money. We worked out roughly how much money the hapu had or would have access to, and then we gave that to them. In that case we figured out that it would be about four million dollars. And then we presented them with a whole range of things that they could spend their money on.

There were actually two of each, and they had a little picture of it. For example: Build a children's playground, update the kitchen [...] but there were also adaptation options like raise or waterproof the buildings and build a stop bank, as well as options to move, buy new land, move and rebuild - and each one of these options was referenced in a little picture and had a cost associated with it.

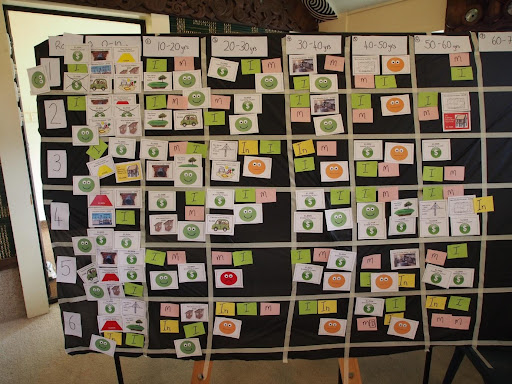

There was also the ability for the players to insure their property and to invest their money. We had fixed interest rates. So we had little pairs of cards that represented all of these things, and what happened was - when the choice was made and paid for, people came up, they purchased an option, we gave them the cards, they took one of the cards back and stuck it on their map, so they knew what the‘ve done. And they took the other card of that pair, and they put it on this huge big map on a board up in front of them, which was about two to three metres long.

There were six groups playing, so we divided up the board - across for the groups and down for the different time segments, as it was played in ten year chunks. And people just stuck their card up on their square for their team and their time frame, so everyone in the room could see it.

So it wasn‘t really a board game as you know it, it was more of a collective activity, in which you could see and hear what everyone else was up to.

And then you began simulating climate change?

On a separate PowerPoint screen we had what we called a Rain Maker, which was really just a whole series of random flood generators, and it worked over that ten year period. So we then just pushed the button, and it would go: ‘year one: no flood,’ ‘year two: minor flood, no damage,’ ‘year three: major flood, major damage,’ ‘year four: no flood.’ So every single year came up, and you could hear the collective breath and the room going “what‘s gonna happen, what‘s gonna happen?” And once that was done, people were told to assess the damage, and that was altered by the [original investment] choice that they made.

Then they had to pay to repair whatever needed repairing. When they came up with having no more money, they changed hands. Then we asked every group to come up in front and explain what choices they‘ve made. We prepared a batch of papers with smiling faces on it, and we asked them to stick them on to their decision cards in the front board, thereby answering the questions: How did it go for you? How do you feel about your choices? And how did your choices meet the listed aspirations of your hapu? How happy do you think they are with you right now?

What type of strategies did they play?

They played very different strategies. Some people bought up heavily in the first little while, and then had to spend a number of years investing money to get their resources back up again. Others ran a different strategy; some were buying land early and then just waited it out. Quite a number of different strategies were played.

But because of that discussion at the end of each round, everybody knew what strategies had worked and who was in trouble. So that was the communal part of it. And they came out of it being able to narrow down and at least to know which choices are not going to work, and what choices would potentially affect their long term ability to adapt.

It was completely designed to start to break down that polarisation of choices, because it is not as simple as ‘stay or go.’ It‘s never that simple. And once the game was played, they realised that they had to be careful with their money and that there are basically two options for them: To raise stop banks or look for new land. So [as part of the game] we taught them to make some decisions and investigate things a little bit more deeply. And that‘s where we sat back and said that the choices to be made going forward now are yours.

What did these group discussions look like? Were they fairly calm or did they get emotional?

It was a pretty noisy room. You know, the beauty of the game is that it isn't real. So it tends to diffuse some of the really intense emotional experience out of it. There were a lot of enthusiastic discussions. And also the trick of these games is to keep it lighthearted. It is a very serious topic, but we still made jokes throughout the process.

Humour is a good antidote to tension, as some authors say. So it was animated, but it wasn‘t extremely emotional.

In a scientific paper from August 2021 you labelled the board game ‘inclusive’ and ‘hybridised’ with respect to indigenous communities. What were some of the salient fears, issues and hopes in discussions within the groups?

I‘m going to draw on other pieces of works here as well - there is always a fear of loss of something of value. So it depends on what is at stake. For some of the elders, there‘s a very deep sense of connection to those buildings and those places because of many years of association, many memories. But the younger people were a lot less connected. They see the problems ahead and say, ‘we should do something sooner rather than later.’

Within every community that I‘ve ever worked with, there are those who have something that‘s of high value to them that they do not wish to lose. And they would do anything to dig in and protect it, like building stop banks or sea walls. And then there are those who tend to take a different view and say, ‘those things are valuable, but in the longer term we can‘t continue to just protect them.’ You see it very strongly with private property, particularly on the coast. They want their house to stay as it is at any cost. And then you get the wider community which realises that if walls go up, they‘ll lose their beaches, and things will then be quite different. There‘s always this kind of interplay within the community. It‘s happening in those communities over and over again, and it does create a deadlock. Hence the game. We tried to bring the games in to show what the benefits and costs are for each choice.

For example, it‘s well known within the scientific community that stop banks fail. They have design standards where they can be overtopped, the land behind will be flooded and damaged and all the levels of services that stop banks currently provide will decrease as climate shifts. So they are actually diminishing returns, really.

But a lot of people still think these stop banks will protect them forever, [although] that‘s not the case. And it‘s basically the same with sea walls: It‘s just not as simple as that. And many folks within the community struggle with the complexity of the problem.

They struggle with the changing nature of risk associated with climate change. We know that the sea will rise by a metre, it‘s just a question of when. And that‘s hard for some people to wrap their heads around.

If you compare the state of communities you played Marae-opoly with before and after the game, did they feel more optimistic because they could see there are solutions that might work or did they get more pessimistic because they realised that sea level rise is inevitable?

I don‘t know. What we tried to give them was a sense of empowerment, so we didn‘t really measure optimism or pessimism before and after. We asked more about feeling empowered to make a choice. To me this is a different question: I think you can feel pessimistic about something, but you can feel that you can at least get your own way out of it. So I tend not to use optimism or pessimism as a measure. I would ask, how empowered do you feel about making choices that allow you to achieve your aspirations?

Were kids or youths involved as well?

Yes. In fact, everyone can play it. We had older people in their 80s, but we also had younger people, teenagers, some even brought kids with them, it was a good mix.

You know, Marae-opoly is quite a complex game, but we do have other games as well that kids could play easily. One of those games is designed to fit into the school curriculum, and we give teachers materials to wrap around the game, so they can work on it in classrooms.

So at the end of the game the communities had to come up with one decision that they all agreed upon?

Not at the end of the game session. But we‘ve been working closely with these hapu, And they then took these conversations forward and used it to make decisions.

They saw that they had two options that they could reasonably consider: Build a stop bank or move. So they looked at both options in more detail and looked around for land to see if they could purchase any. And that initially didn‘t work. So they also looked at building a stop bank. But they discovered through more detailed engineering work that they could build up a stop bank, but it would be quite wide. They did have the money to act, but they waited for the right moment. And that is something they also learnt with the game, that waiting could also be a good option.

And more recently, a block of land right next door to them, just up the road, has become available, and they have purchased that. So they are now looking to move. The game allowed them to really come to a collective understanding of the problem, and the benefits and costs and limitations of each of the options in front of them. So no decision came out of the meeting at the end of the day, but the conversation went on and on, and then they got to a point where they finally decided what to do.

Did you try out the board game outside New Zealand?

No. We‘ve been busy developing it for a local application. But we‘ve played Marae-Opoly with other people who don‘t have a connection to that particular place. For those without a connection to the place, for instance, the game is played differently, because the attachment to places is really strong in some people, but if they don‘t have that connection, they will make other choices.

In any difficult decision-making setting, where a community has to make some tricky choices about what to do, you would put in a game that is specific to them, so again - going through the process of what are the aspirations, where are the disagreements, what are the options, what are the limitations of these options, what are the hazards they‘re facing, etc. and then packaging it all up to something that would work for them and allow them to think through it.

Dr. Paula Blackett is an environmental social scientist at NIWA, New Zealand.

Image by NIWA.

By copying the embed code below, you agree to adhere to our republishing guidelines.