- About

- Topics

- Story

- Magazine

- In-Depth

- Picks

- Opinion

- News

- Donate

- Signup for our newsletterOur Editors' Best PicksSend

Read, Debate: Engage.

| January 04, 2023 | |

|---|---|

| topic: | Death Penalty |

| tags: | #Pakistan, #death penalty, #capital punishment, #Mental health |

| located: | Pakistan |

| by: | Samia Qaiyum |

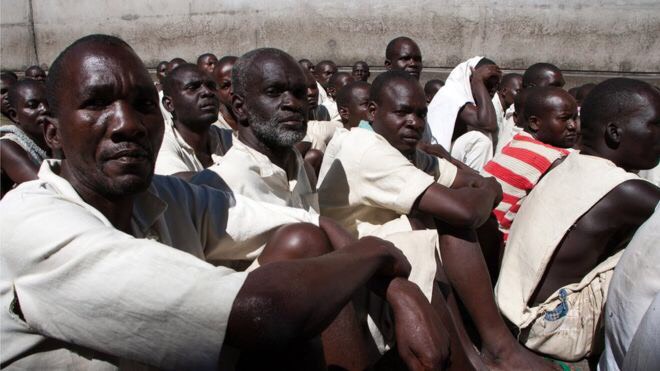

The statistics are grim. While global consensus against the death penalty continues to grow, analysis of data from 2013 to 2018 found that Pakistan was home to the largest reported death row population in the world - nearly 26 percent of the world’s recorded death row of roughly 18,300 individuals.

Alarmingly, the 4,688 prisoners awaiting execution (often under miserable conditions in overcrowded jails) included juvenile offenders, women and those who are mentally ill.

Still, it's not all bleak as one non-profit called Justice Project Pakistan (JPP) is not only representing the most vulnerable prisoners facing the harshest punishments, but also advocating to criminalise torture and educate government leaders on how death penalty implementation violates human rights standards through briefings, op-eds and workshops.

Through public advocacy, meanwhile, JPP takes a slightly lighter approach in order to convey its message – interactive games, large-scale art installations, media productions and performance art. A recent play entitled Limbo, for example, featured a dramatic reading of letters by prisoners on death row, interspersed with passages from George Orwell’s essay ‘A Hanging’ as well as regulations from the Pakistan Prisons Rules.

Winner of the inaugural Franco-German Human Rights Prize in 2016, JPP was founded by Sarah Belal, an Oxford-educated barrister who defies the stereotype that lawyers are dispassionate. She’s brought to tears at the memory of her very first client, Zulfiqar Ali Khan, a prisoner who spent 16 years on death row and devoted that period to educating himself and other prisoners before his execution in May 2015.

Belal spoke with FairPlanet about JPP’s origin story as well as the highs and lows of its advocacy and litigation work.

FairPlanet: What was your initial inspiration to establish JPP?

Sarah Belal: JPP started in December 2009 in the back of my father's office - but we paid him rent! But going back even further, it was myself and Maryam Haq [Legal Director of JPP]; we worked together at this civil law chamber, and we'd talk about how the law needs to mean something, how we should do work that inspires us.

I was an intern at the time, and found myself between jobs a few months later. And because I was nearly 30, my parents staged an intervention insisting that I get up and get a job, whether it inspires me or not. With time, I established a proper morning routine and was reading the paper, which featured a letter from a prisoner who was due to be executed in a week.

It was his plea, asking for anyone out there to help him. He talked about how he had two daughters, how his wife had died from cancer, why he was incarcerated, and the fact that he was poor. Reading that, I felt sick to my stomach. Even as a child growing up in Pakistan, there would be these short news reports - ‘prisoner hanged’ - and it always felt like a very strange thing to simply read and walk away from. But I'd never read a letter from a prisoner, so it really affected me, but I had no idea where to begin.

Then, with every inane action like brushing my teeth, I'd think, ‘How would I feel if I knew I was brushing my teeth for the last time?’ I just couldn't get out of that thought process. And it made me sick knowing that a human being knew exactly when and how he would die – and there's nothing he can do to stop it.

Eventually, I called the paper, convinced that somebody would've responded. They were clearly very busy and impatiently asked if I was a lawyer and willing to represent him. As a very junior lawyer, I hesitated, so they hung up. And only 30 minutes later, I got a call from his brother, asking if I'd take on the case. Despite my insistence that I was too inexperienced, he was at my doorstep an hour later.

The case had been rejected by the Supreme Court, so no lawyer was willing to take it. Still, I approached every single mentor of mine. Their advice? ‘Nothing can be done, so don't get emotionally or personally involved. And don't begin your career with unwinnable cases because it won't be good for your professional reputation.’ It was sincere advice, but baffling to me.

The idea of not taking a chance when it's literally a matter of someone's life just didn't compute. And what professional reputation? I didn't have one! I started by visiting the inmate, and it was actually the first time that I'd ever been to a prison.

Going to that prison and looking at the sheer scale of death row around me, I felt completely overwhelmed. ‘This is just too big a problem to solve. And I don’t owe this to anybody.’ And as I was saying these things to myself, I had tears running down my face because I knew that I would never be able to live with myself if I walked away.

And did the prisoner's execution go through?

We were able to get him a stay of execution from the president. And then that was the beginning of the moratorium declared against the death penalty in 2008, so we had six beautiful years.

After his case, I started getting more and more cases of death row prisoners. Now, a lot of my early legal career was me trying to figure out how to do what my mentors abroad - who were very famous capital defence lawyers - were telling me, and then kind of fitting it into the Pakistani system while tapping my mentors in Pakistan for their strategies [...] but no one had any expectations – I was a woman and a young lawyer [...] so I could fail countless times as I learned my craft.

With time, I won a capital case. And then the work started getting a bit much. That's when my husband kicked me out of our guestroom because our home was being engulfed with papers. He gave me a loan, which was sheer privilege - the ability for me to experiment, to be in touch with the mentors that I had, and to navigate such spaces as a woman was all completely rooted in privilege. I want to be very upfront about that. Even the 50,000-rupee loan was a privilege back in 2009.

I called up Maryam, who I really needed because I didn't know how to draft. I was really good at research and thinking through a case and putting things together, but Maryam was exceptionally good at drafting. I promised her an adventure, so she took a pay cut and joined me. All we had was a donated computer and a couple of reupholstered sofas before we started going to prisons and litigating on behalf of people who we wanted to help.

One fellowship later, JPP was an established organisation. But going back to your question, the prisoner was executed in 2015 after the 2014 attack in Peshawar led to a lifting of the moratorium. It was devastating.

So where does Pakistan stand today in terms of capital punishment?

Our country needs to be studied. No other country in the world has had [such a] trajectory with respect to the imposition of capital punishment. I think it is an amazing case study on what is possible, what can go wrong, and what can go right just from looking at the past 13 years.

What I mean is having a de facto moratorium, the largest death row in the world, and a list of 33 crimes that merit the death penalty to the Peshawar attack, lifting the moratorium, shooting straight up to the top three of annual executions to then rolling it back - and then also just education and understanding that this isn't working for us.

And now going back to what is essentially another de facto moratorium - we haven't executed for almost three years now - to reducing the number of crimes that merit the death penalty.

But then again, this is what I say about Pakistan: we are always just one terrorist attack away from them lifting it, so you know, there's immense gains and there's immense progress. And I think there's a lot of strategic lessons to be learned if you look at Pakistan - maybe we're very specific? Yes, every country's trajectory towards its death penalty regime is very personal, but I think there are larger lessons that can be learned regardless, so it is a story of hope as well.

Following the ‘Safia Bano’ judgement, Pakistan ended the death penalty for prisoners with mental health problems in 2021. What can you reveal about JPP's role in this milestone policy-shift?

One of our first clients was mentally ill. I remember Maryam and I going to Central Jail Lahore, which is where they keep death row prisoners. They can't leave their cells, so if you represent them, you have to walk all the way into the prison and meet them outside their cell – so we actually get to see every prison cell that our clients are in.

One of those times, there was this lady in her 60s who just grabbed my arm and asked if I was a lawyer. As soon as I replied, she demanded that I meet her son, Khizar. Maryam and I were taken aback as she dragged me, wondering if prison officials would stop her.

Basically, Khizar was severely mentally ill and had been on death row for a murder case for years. She had been visiting him regularly, and the entire prison staff knew her. And they knew not to mess with this woman because she was just the biggest battle axe - with nothing, by the way. They had nothing.

I remember Maryam and I going to see Khizar, who had stitches that were still raw across his face, almost like Frankenstein. I couldn't believe that someone so mentally ill was being kept with other prisoners who would attack him out of sheer frustration.

Khizar was the first severely mentally ill person who we started representing and trying to save, trying to get the mental health act enforced was a losing battle again and again and again. But through his case, we learned that we keep getting this medical evidence and we understood all of the structural issues that were faced by prisoners with psychosocial disabilities.

Simultaneously, we were doing two trials in which our clients were paranoid schizophrenic, so it was learning on the go.

We were also trying to get experts to testify, so we started building these pockets of professionals that we interacted with – mental health experts being a big one. We started asking for records; back then, lawyers weren’t privy to the mental health records of their clients.

Then, it became about understanding that even if you get the right expert and the right evidence, the justices do not understand the varying nature of mental illnesses and their implications on criminal intent. That's when we started getting into judicial training, and holding conferences and seminars for the superior justices because there's no point in having all the best evidence in the world if the people that you're arguing with do not know the difference between epilepsy and schizophrenia.

It was years and years of building that know-how, putting all of these segments in touch with each other, and then those challenges making their way up to the Supreme Court - what seems like an overnight success was 10 years in the making.

At the end of the day, it was beautiful when all four provinces, their advocate generals, and prison authorities were in favour of this judgement. Now, the challenge is having that judgement applied.

Those with mental health issues aside, JPP represents the most vulnerable of Pakistani prisoners. Can you paint a picture of who they are?

The harshest punishments is our measuring stick, so don't do legal aid. We work more strategically, which means that we take test cases – we investigate, we uncover and then we put together test cases that we bring before the superior courts as a way to break through. Because if you win that, you set a precedent that can then be applied across the board.

And sometimes, even when you lose on the way to litigating, you have some other gains that can procedurally benefit people across the board. That's our methodology. In that, we need to have a yardstick of the kind of cases that we take, so number one is capital crimes because the standard for the most vulnerable facing the harshest punishment.

In the past, we've had incredibly wealthy people who are facing extreme punishments and can afford to have very good lawyers, so we will not take their cases. It has to be that you have to have a key vulnerability – that could be poverty, mental illness or a particular bias that the public or government has against you.

Then, it has to be extreme sentences, so it has to be the death penalty or something right below it. Usually, with the largest reported death row in the world, we have our hands full with capital cases, but we also represent overseas Pakistani prisoners facing harsh punishments because their vulnerability is extreme as well.

Our overseas work is something that we're very proud of. We started in 2013, and we've made some very good gains. Admittedly, this is a very bad time to talk about it because one of the key countries in which we were making gains, which is the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, restarted executing Pakistanis in the last two weeks. And we're very upset about that.

Early on, during the height of the war on terror, our clients also included Pakistanis who had been held at Bagram Air Base under control of the Americans. But I'm happy to report that we got all 43 of them back.

JPP has long advocated to criminalise torture. How do you think the recently adopted Torture and Custodial Death (Prevention and Punishment) Bill will alter the landscape?

It's a starting point - laws don't change the world, but you need a law in order to be able to litigate. At JPP, we say that the only kind of cases we've never successfully managed to litigate have been torture cases because the plethora of laws spread over and the lack of a law defining torture and protecting victims in order to litigate was the thing holding us back, so it's a huge moment.

It's a huge accomplishment for the country, but this is a starting point and it's going to be a huge focus of our work going forward – how do you litigate, what is the legal framework that allows this law to actually take place, what are the standards of investigation for the various stakeholders that have been identified.

But we won't pat ourselves on the back and walk away. We want Pakistan to be a shining example of how not just passing a law on torture, but setting up an entire system that is geared to prevent torture and hold perpetrators accountable.

I was in a meeting with some stakeholders in Geneva, and I was informed that there is no country right now that stands out in terms of effective implementation of this legislation, and I'm obsessed with making Pakistan just that.

Lastly, another area of focus at JPP is identifying and exposing key problems in Pakistan's penal system. Can you elaborate?

We only talk about it in the context of prisons, as well as the evolution and management of prisons, so my views on anything in the public sphere are solely connected to prisoners.

We recently released a book about Pakistan's prisons, and one of the big things that we're always propagating is to look at things in the context of their history – whether we're looking at the law, policy solutions or something else. Because only then can you understand how something has evolved and what would be possible solutions that are effective and strategic. That's something most people forget to do, whether you're trained as a lawyer or otherwise. And I'm always baffled by this. How can we think that we live in very special times?

There's a trajectory of human history and if you actually go through it, you will learn lessons from the past and spot indicators of what would and wouldn't work.

Maybe I do that because I was a history major before I studied law, but whether I'm looking at a case or at an institution and its evolution, I'm always looking at it in its historical context. And that tells you the story and tells you what's more likely to succeed going forward or not.

That's kind of what we do when we talk about prison reform. When we sat down to write a book, the first question we asked is, ‘Should we even be writing one?’ And when we looked up what had been written every year for 70 or 75 years of Pakistan's existence, there has been some federal or provincial or an NGO or civil society report coming out, so clearly, there is nothing to be said to add to that.

But what we did want to talk about is really looking at the history of each province's inspectorate of prisons and its evolution over time.

This is because unlike most other institutions, prison inspectorates are deeply, deeply rooted in their provincial histories. And looking at the question of who's in prison, in what province, for what offense and what their lived experience in that prison is like is very much connected to the trajectory and the socio-political, economic, anthropological evolution of that province and its context.

It's not even just the colonial lens in all four provinces and the colonial experiences - it was different in all four provinces. In fact, it was the Brits who really hammered down these ethnographic differences. And so, it's really looking at the evolution of each province's prison system in that context.

When you look at Pakistan's prisons and talk about reforming our prison system, you have to break it down by province and understand the particular history of each province to understand who's in prison, why, and what you need to do to fix it.

By copying the embed code below, you agree to adhere to our republishing guidelines.