- About

- Topics

- Picks

- Audio

- Story

- In-Depth

- Opinion

- News

- Donate

- Signup for our newsletterOur Editors' Best Picks.Send

Read, Debate: Engage.

| April 30, 2025 | |

|---|---|

| topic: | Climate Change |

| tags: | #heatwaves, #climate change, #pregnancy, #maternal health, #prenatal care, #Pakistan, #Karachi |

| located: | Pakistan |

| by: | Hamna Iqbal Baig, Faisal Rehman |

New research from 2024 found that every 1°C rise in temperature, the risk of preterm birth increases by 4 per cent and that extreme heat exposure can increase the risk of preterm births by up to 26 per cent. For women living in overcrowded, poorly ventilated homes, that danger is not a future threat - it is a daily, stifling reality.

In January, Samira, 29-year-old first-time expectant mother, gave birth prematurely at eight months. Her baby was stillborn.

She lives on the fourth floor of a completely enclosed concrete building in Lyari, Karachi. During her pregnancy, she struggled to cope with the intense heat trapped inside her poorly ventilated apartment and experienced severe dehydration.

"The doctor told me that she suspects my child didn’t survive due to extreme heat and dehydration," Samira recalls, her voice heavy with grief.

"I feel like I failed to protect my child," Samira lamented.

While the reasons behind such losses are often multifaceted, emerging research increasingly points towards a significant factor: heat exposure during pregnancy.

Several studies corroborate this potential link. A 2024 review analysing data from low and middle-income countries indicated that most of the examined studies found a connection between high ambient temperatures and stillbirths. This aligns with a more comprehensive 2024 meta-analysis of global research, which revealed a 13 per cent increased risk of stillbirth associated with high heat exposure. Even a groundbreaking 2023 study in India, observing pregnant women engaged in physical labour, noted a correlation between heat stress and adverse outcomes, including stillbirth.

Samira’s experience is not unique.

The area of Lyari is characterised by narrow alleys, tightly packed low-rise and mid-rise buildings, unplanned densification, limited ventilation, and lack of green spaces. This layout intensifies the effects of extreme heat for the town, particularly during the summer months, and gives rise to a phenomenon known as the urban heat island (UHI) effect for its nearly 950,000 residents.

Pakistan’s metropolitan city, Karachi, suffered a severe heatwave, with temperatures soaring above 40 °C and peaking at 47.2 °C in June 2024. Alongside high humidity levels, the real-feel temperature reached up to 49 °C. Prolonged power outages added to the distress, with power cuts lasting 10 to 12 hours daily, leaving city residents without fans or cooling systems.

Another resident of Lyari, Nahida, went into early labour in November 2024 at just eight months and 20 days and delivered her baby at Jinnah Hospital, Karachi’s largest public healthcare facility.

"I remember that day clearly," Nahida said. "I thought I was having normal pregnancy pains and went to my doctor for a check-up. My husband took me to the hospital in a rickshaw, but it was quite warm for November."

When she reached the hospital, doctors informed her that she needed an emergency cesarean section, although her baby was not due for another three weeks.

"The doctor said that the heat had put too much stress on my body, and it was starting to affect my baby’s development," Nahida explained. "I agreed to the operation because I didn’t want to lose my child."

The 32-year-old felt hot even at night inside her home, a three-story concrete building without proper ventilation. This made it impossible to find relief during peak summer months. "The heat was suffocating, even after sunset," she said. "There was no escape."

Sharmeen Ali, 38, was also in a similar situation. First, she was admitted to the hospital on 3 May 2024 due to dizziness and pain but was discharged two days later. Her doctor said she was due after 3 to 4 weeks. But she went into labour unexpectedly on 7 May. The contractions came suddenly, and before she could reach the hospital, she delivered her baby alone in the bathroom of her home.

"I don’t understand how I delivered early when, during my last doctor’s visit, I was told there was still time," she said. Throughout her pregnancy, she felt extremely dizzy and spent most of her time sleeping. Her doctors repeatedly advised her to drink plenty of water, warning that the heat could deplete her body of essential nutrients.

Dr Jaya Shreedhar, a doctor-turned-journalist based in Chennai, India, explained that heat stress can have serious consequences for both the mother and the fetus. "Elevated maternal core body temperature can directly trigger uterine contractions, leading to preterm labour or miscarriage," she said. According to her, this happens because the body misreads the temperature spike caused by heat as a signal to initiate labour.

The expert explained that high heat exposure can also raise fetal heart rate, an early sign of fetal distress and dehydration that further complicates matters by reducing blood flow to the placenta. "This limits the delivery of oxygen, nutrients, and water to the fetus, which can restrict fetal growth and, in prolonged cases, lead to stillbirth," she noted.

Shreedhar also pointed out that heat stress triggers inflammation and oxidative stress in the body, damaging tissues and nerves. These responses, she said, are part of a broader physiological strain that contributes to poor pregnancy outcomes. "Electrolyte imbalances resulting from dehydration can disrupt hormonal balance and bodily functions, increasing the risk of preterm labour," she said.

Another expectant mother from the area, Anita, said the heat made her pregnancy even more difficult.

"The moment I stepped into the kitchen, I felt like I was standing inside a furnace. My head would start spinning, and my clothes would be soaked in sweat. I had to keep stepping out just to breathe," she recalled.

At one point in October 2024, the 35-year-old was admitted to the hospital due to acute gastritis for a day. Her family noticed she had become weak. She often left meals unfinished, completely losing her appetite and her body drained of energy.

Faiza, 29, was expecting her second child. During peak summer months, she felt dizzy on the second floor of a three-storey building in a congested lane. Her blood pressure dropped, a common risk during pregnancy when the body is already under heat stress. She is relieved to have delivered a healthy baby weighing 2.5 kg on 3 February 2025.

Samreen also gave birth in February 2025 after enduring months of heat-related stress. While her child was born safely, her pregnancy journey was marked by constant physical and emotional strain due to the heat.

"I felt weak all the time, and my blood pressure stayed low. No matter how much water I drank, it never felt enough," she recalled. "I had been pregnant twice before, but the heat was unbearable this time."

Like other pregnant women, she faced dizziness, fatigue, and dehydration. Even mild exertion left her breathless, and she often experienced swelling in her hands and feet, something she hadn’t faced in her previous pregnancies. On particularly hot days, she noticed a worrying decrease in her baby’s movements, which made her anxious.

During her prenatal checkups, doctors repeatedly warned her about the risks of heat stress and dehydration, advising her to rest and stay cool. But her home had trapped the day’s heat even after sunset. "The heat didn’t go away at night. My house felt like it was radiating warmth from the walls," she explains.

The women adopted simple yet desperate cooling measures to cope with the intense heat while experiencing power outages lasting 10 to 12 hours. Samreen and Faiza poured cold water on the floor before sleeping, hoping to lower the temperature. Faiza also sat by the window for ventilation, took multiple showers, and drank lemon water to stay hydrated. Anita wrapped a wet cloth around her head and took frequent showers, though the relief was temporary.

While these women were housewives and spent most of their time indoors, the heat trapped within the four walls of their poorly ventilated homes, long hours of power cuts, commutes to clinics or hospitals in public transport, and the time spent cooking for their families all added to their exposure to heat.

Within Pakistan’s context, the severe health impacts of extreme heat on pregnant women, including preterm birth, stillbirth, maternal hypertension and other pregnancy complications, were highlighted in a November 2023 report based on interviews with 16 pregnant and postpartum women in the Sindh province.

An ongoing four-year study launched in 2024 by the Aga Khan University (AKU) study is expected to be the first comprehensive body of evidence from Pakistan examining the effects of heatwaves and heat stress more broadly on pregnancy outcomes.

The study aims to provide concrete, context-specific data on how extreme heat affects pregnancy outcomes by tracking 6,000 pregnant women across rural Sindh (Tando Muhammad Khan, Tharparkar, Matiari) and low-income urban areas in Karachi (Kharadar, Dhobi Ghat, Korangi). It accounts for overlapping social and environmental stressors - such as cramped housing, the burden of cooking during pregnancy, and limited access to cooling - amid projected temperature rises of 2–5°C in Sindh by 2100.

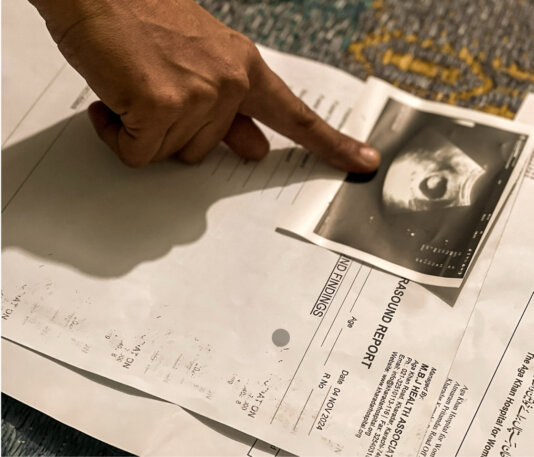

"The team is using wearable devices such as Fitbits and iButtons to track individual heat exposure alongside medical assessments like ultrasounds and blood tests," shared Dr Jai Das, a public health researcher and assistant professor at the Department of Paediatrics and Child Health at AKU.

He highlighted that they are still in the early stages of fully understanding how heat stress impacts pregnant women, particularly in South Asia, where populations are more accustomed to high temperatures. "Heat stress is not universally defined," he explained, "because it varies by context. In regions like Europe, heat alerts are issued at much lower temperatures compared to South Asia." This variation highlights the need for more localised definitions and data.

One of the key unanswered questions is what matters more in heat exposure - intensity, duration, or frequency. "While our preliminary data is consistent with existing research," Dr. Das says, "we require more detailed, context-specific evidence to draw definitive conclusions."

In countries like Pakistan and India, where maternal and infant mortality rates are already high, Dr Das noted the importance of comparing heat-related health impacts against baseline mortality statistics. "Only by comparing populations exposed to different temperature levels can we assess whether heat is responsible for increased mortality or adverse pregnancy outcomes," he said.

Another significant gap in research is understanding the long-term consequences of chronic heat stress. Although immediate effects like exhaustion, dehydration, and fainting are well known, he warned that "emerging evidence suggests heat stress may also contribute to cardiovascular issues, psychological disorders, and even childhood stunting."

Dr Das hopes that once AKU‘s study is completed, its findings will lead to actionable healthcare guidelines to protect pregnant women from extreme heat.

Karachi, once known for its moderate coastal climate, is facing a growing crisis of extreme heat, primarily attributed to the Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect. This phenomenon occurs when urban areas experience significantly higher temperatures than their surrounding rural counterparts due to the absorption and retention of heat by buildings, roads, and other artificial surfaces, coupled with a lack of vegetation.

Anjum Nazir Zaigham, Deputy Director at the Pakistan Meteorological Department (PMD), noted the severity of UHI in certain localities. "It is true that Lyari Town is considered the largest Urban Heat Island in Karachi. Characterised by low- and mid-rise concrete buildings with poor ventilation, the area experiences some of the highest temperatures in the city," Zaigham said.

"Lyari is the only town in Karachi with 1.5 to 9.0 per cent greenery - a combination of factors contributing to it being the hottest area in the city."

The lack of trees, parks, and shaded areas not only exacerbates the heat but also limits communities' ability to adapt to rising temperatures. Urban planner Muhammad Touheed pointed out that while a heat management plan exists, it remains largely unimplemented. He emphasised that “Effective solutions are cooling centres used in areas worldwide that experience extreme heat, restoration of water bodies and the creation of urban forests as long-term mitigation strategies.”

Karachi’s Early Warning System (EWS), developed in response to the deadly 2015 heatwave, is key in issuing alerts and coordinating responses during extreme heat events. While it has helped reduce casualties, it remains insufficient, particularly for women in low-income areas who often lack access to these alerts or the means to act on them.

Despite the escalating threat of extreme heat, no specific measures are in place for pregnant women at Karachi’s government hospitals, where families struggle to secure even a single bed during heatwaves, hospitals face severe overcrowding, no designated accommodations for pregnant women exist, and there are no comprehensive mechanisms to monitor heatwave-related deaths.

Sindh Health Secretary Sohail Ahmed Qureshi acknowledged that although at least 45 response camps were set up across the city and heatwave guidelines were disseminated during the last heatwave, efforts to reach pregnant women in low-income areas had been inadequate. “A mechanism is currently being developed and will soon be in operation,” he said, but admitted there were no clear policy-level interventions yet to address the intersection of heat and pregnancy.

Dr Rana Dildar, Vice President of the Young Doctors Association Sindh, echoed these concerns. She said, “The fundamental issue is that this has never been viewed as a public health concern in the public sector hospitals.” She added that despite witnessing the impact of extreme heat on women’s health and pregnancies firsthand, there is still minimal evidence in official records or research addressing this critical issue.

The recent 2024 heatwaves underline the urgency of more inclusive strategies. May saw a 1.41°C increase in minimum temperatures compared to 2023, and by 25 June 2024, the heat index peaked at 49°C, resulting in 141 deaths in a single day and over 568 deaths overall in Karachi. Forecasts suggest that Karachi’s future climate may resemble arid Saudi cities, with summer temperatures rising by over 3.3°C (6°F).

Experts and research indicate early warnings alone are not enough. Without access to solid evidence or research, emergency maternal healthcare, uninterrupted power and safe cooling centers, the specific needs of pregnant women and other vulnerable groups will continue to be dangerously overlooked.

This story was produced with support from Internews' Earth Journalism Network.

Image by Hamna Iqbal Baig.

By copying the embed code below, you agree to adhere to our republishing guidelines.