- About

- Topics

- Story

- Magazine

- In-Depth

- Picks

- Opinion

- News

- Donate

- Signup for our newsletterOur Editors' Best PicksSend

Read, Debate: Engage.

| April 30, 2021 | |

|---|---|

| topic: | Economic Opportunity |

| tags: | #Geographic Indications, #intellectual property rights, #Africa, #colonialism |

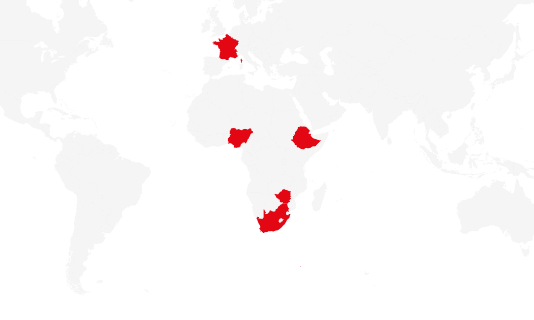

| located: | Nigeria, South Africa, Ethiopia, Zimbabwe, France |

| by: | Frank Odenthal |

However, many African countries are struggling to protect their valuable unique products. With the exceptions of South Africa‘s Rooibos tea and Ethiopian coffee, there are only few examples of successfully implemented Geographical Indications of African products.

FairPlanet asked Dr. Samuel Andrews, an expert in intellectual property rights, what it‘s all about.

FairPlanet: would you have an estimate of the value of intellectual property rights in Africa?

Samuel Andrews: Unfortunately, we don‘t have accurate data on property rights in Africa. But I would say what Africa is missing out on is a lot. Europe is getting a lot more, but that‘s partly because they‘re poaching in Africa, and that tells a lot. There are a lot of assets in Africa, and if they do the right thing and protect them by appropriate property rights, that would be a big issue for African economies.

How were these Geographical Indications property rights developed?

Geographical Indications in fact is an old construct. The first system formally started with the so-called Lisbon Law. It‘s basically a central system. If you want your Geographical Indication for example for your food ressources, your cheese or your chocolate, to be protected, there was this first - you could call it the grandfather of property rights - the Lisbon Law.

But when we talk about property organisations, people thought that this law wasn‘t easy enough. They wanted a kind of a central system where more people come and register their products easily, not in a complicated system. There are still other systems in place in certain parts of the world, but the Lisbon system is now the domínant one.

Can only governments protect the country‘s products? Or is it accessible for anybody who wants to protect their items?

I‘m afraid for Geographical Indications on your products you need your government to work on it, to provide it. The United Nations jurisprudence would not allow for individuals to come and protect their products on their own. If they would allow that, in terms of politics and reality, it‘s gonna be really impractical. It is based on treaties which only states can sign. You need to enforce it, but you can‘t enforce private rights or public rights without the backing of state orders. And that‘s the reason why African states are not really good at Geographical Indications. They are not really getting into it.

For example, Nigeria is the biggest economy in Africa right now, there‘s such a big market, but there‘s no law, no effective protection of property rights whatsoever. There are moves now to recognise these treaties. But Nigeria is not there yet. Some countries are partly there, like Ethiopia, but others are not.

You know, there are a lot of Geographical Indication issues affecting climate change. Because if we really want to promote a good environment and a good world, we should leverage the traditional method of producing food, and at the same time recognise how to protect it. So African governments should really come in and join these efforts to protect the traditional ways of production.

Our forefathers were conscious of our environment while producing food, and we should protect and save their knowledge. If governments come in, it will therefore boost our efforts to fight climate change, it will also boost our economies and cross-border trade.

Why are there only so few countries joining these efforts to protect their property rights and signing on to those treaties?

It‘s certainly not a lack of knowledge. We have really decent universities all over Africa and so many very smart people coming out of it. I do see two reasons for African countries not joining the treaties yet. The first reason is political: Africans are still scared of the dregs of colonialism. You have to be careful what you sign, you know, you don‘t want to sign your life away. All these documents, and people are reluctant to sign, because they‘re afraid.

Africa needs to look upwards to people like me, well-educated people working in the diaspora all over the world. We‘re expats in this field. Our African political leader should reach out to us, as experts in this field we might be able to give advice, but instead they wait and sit at home and look at these documents. They should reach out to us, we could tell them to negotiate this clause, or do other things. Because we‘ve got the experience, we could give good advice. They‘re scared to sign, but they don‘t want to reach out - and I don‘t know why. In most of the African countries you‘ve got extractive economies. They believe in oil, because oil brings quick money. They believe in gold and all these resources that lead us to wars and conflicts. But they don‘t see that growing food in a good soil can bring you big money, too. That‘s one part of it.

The other reason, we cannot get away from it, is expertise. I don‘t want to mention names of countries, but I‘ve talked to most of these political leaders. Some of them were surprised to hear about Geographical Indications to protect property rights. They‘ve never heard about it before! And I was shocked. These are people who are in charge of property rights in certain countries, but they‘ve never heard about Geographical Indications.

You know, I was talking the other day with people saying why is it that you guys are not calling us to give advice, because others are charging fees for their advice, but you could give it for free. But why is it that nobody reaches out to us? I don‘t know why. Maybe they think Geographical Indications are not bringing them money, you know, politicians always want to have quick money. That‘s in my opinion what the problem is.

Is there a good example of a country in that respect in Africa?

Well, South Africa is doing a great job here. And Zimbabwe, too. Those two countries they are really doing a good job. They are struggling, but they are at least willing to change their law to comply with the world we‘re living in. In terms of Geographical Indications laws and regulations they are doing a good job. I wished that Nigeria and Ghana would soon join, because those are big economies in Africa, so that other, smaller countries would have the confidence to join.

Is there a difference in these matters between anglophone Africa and francophone Africa?

In a good way, francophone Africa is doing better. It‘s better, but I don‘t like it. I don‘t like why they are doing well. Because France still plays a big role in Africa. Some say they still got territories there, they are not countries. It‘s like those countries still take and accept rules from Paris. France is really one of these European countries that has leveraged [their] intellectual property rights laws. They know most of the advantages of these cultural issues. They take it very seriously. And it‘s easily transferred to the African country‘s codes.

We have two systems of registration in Africa. One from francophone Africa, one from anglophone Africa. Why should we still have two of them? And when we‘re talking about one big African market, you know, we‘ve just signed a continental free trade agreement - why are we marginalising ourselves internally? Why don‘t we have one central system to register all property rights? Maybe now it‘s time for the governments to come together to get a central system, to streamline the trade laws and also reduce the costs of doing business.

Because as a lawyer the first thing you always tell your clients is how much it is going to cost to register a business. Also they want to know how much it would cost to register their trademark, to register their Geographical Indications. So if you make the costs of registering Geographical Indications higher, they won‘t believe it would make sense to do so. It‘s abstract. As a teacher, like me, you even find it difficult to break it down for your students how these concepts work. So you really have to make the process easy for farmers and others to accept it.

How could the situation around Geographical Indications in Africa be improved?

Well, first of all I must say that the universities are letting us down here. We have some very sound, very solid universities in Africa. But they‘re not teaching Geographical Indications. I can tell you, because I‘m currently doing research in that field. I spoke to universities in Nigeria, in Ethiopia, in Gambia. They are just teaching basic intellectual property rights issues like Copyright. But they don‘t teach Geographical Indications! Moreover, about 95 percent of them in fact never heard of it. They just don‘t know what Geographical Indication means. So, that shows you, where we need to start.

Samuel Andrews is a Professor of Intellectual Property Law and a USA Ambassador’s Distinguished Scholar at the University of Gondar School of Law, Ethiopia. He holds an SJD from Suffolk University Law School, USA. He is also an Adjunct Professor of Legal Environment of Business, Cyber criminology, Criminology and Criminal Justice at Albany State University, USA. He is a former lecturer in the Doctor of Juridical Science Colloquium at Suffolk University Law School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA. He holds an LL.M in Intellectual Property & Law Policy from the University of Washington, Seattle, USA. He also holds an LL.M in Jurisprudence, International Law and Legal Theory and an LL.B (Hons), both from the University of Uyo, Nigeria. He is a Barrister-at-law in Nigeria.

Image: Paul Golding.

By copying the embed code below, you agree to adhere to our republishing guidelines.