- About

- Topics

- Picks

- Audio

- Story

- In-Depth

- Opinion

- News

- Donate

- Signup for our newsletterOur Editors' Best Picks.Send

Read, Debate: Engage.

| July 01, 2023 | |

|---|---|

| topic: | Refugees and Asylum |

| tags: | #migrants, #Mediterranean Sea, #European Union, #asylum seekers |

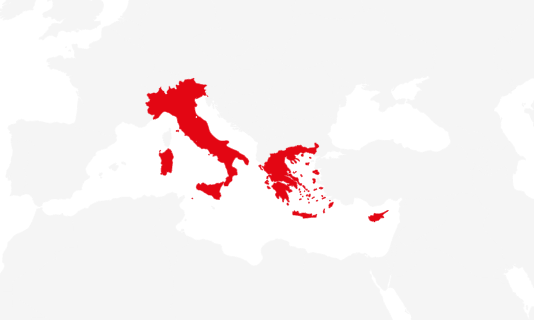

| located: | Greece, Italy, Cyprus |

| by: | Marc Español |

The tragic incident of the boat, laden with hundreds of migrants, sinking in the deep waters off southwestern Greece on 14 June, promptly escalated to become one of the deadliest shipwrecks ever documented in the Mediterranean Sea. But it was far from an exceptional case this year.

During the first three months of 2023, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) documented the deaths of 441 migrants in the Central Mediterranean alone, the highest number since 2017, amid reports of systematic negligence by southern European states.

In the case of the ship that sank off Greece, authorities have recovered 81 bodies and managed to rescue just over a hundred individuals. However, the tragedy has also shed light on another frequently disregarded aspect of such incidents: the individuals who remain missing, which in this particular case reached 500 people.

Since 2014, IOM’s Missing Migrants Project (MMP) has documented over 27,000 people disappeared in similar circumstances.

"The scale today of disappearances at [the Mediterranean] Sea is huge," Lucile Marbeau, a spokesperson at the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), told FairPlanet.

While attention is given to migrants who successfully reach Europe, with their numbers promptly tallied and assessed, significantly less focus is given to those who vanish at sea. Often, these individuals go unnoticed, leaving behind distraught families desperately searching for any trace of their missing loved ones.

"If you think of the ripple effects: how many relatives are there per person? How many friends? How many loved ones?" Marbeau continued. "When you think of the consequence this has in figures, there will be hundreds of thousands of people impacted."

The Central Mediterranean route, which mainly extends from North Africa to Italy and was the one initially taken by the trawler that later sank off Greece, is the world’s deadliest known migration route. This is mainly due to its length, the use of unseaworthy overloaded boats, delays in search and rescue operations and barriers to NGO activities.

On this route alone, the MMP has recorded over 17,000 deaths and disappearances since 2014.

In comparison, more than 2,000 deaths and disappearances of people on the move have been documented by the MMP on the Western Mediterranean route to Spain during the same period, and an additional 1,700 cases on the Eastern route to Greece, Cyprus and Bulgaria.

But this, they warn, could well be just the tip of the iceberg, emphasising that determining the exact number of missing individuals at sea is an exceedingly intricate endeavour, as numerous shipwrecks go unnoticed. There are instances when boats vanish without any survivors, and unidentified bodies washed ashore may not be immediately linked to a specific maritime accident. This complexity underscores the challenges involved in comprehensively accounting for those who have gone missing.

"I am very worried that there are many people disappearing without a trace, whether that’s entire boats going missing or [that] the authorities conducting search and rescue are not necessarily always asking the people on board if someone’s missing," Julia Black, project officer of the IOM’s Missing Migrants Project, told FairPlanet.

"There’s quite a lot of cases this year of remains washing ashore in North Africa, where we don’t know of any shipwreck," she added, "and that for me is a sign that there are many, many cases that we are unable to document."

Migration routes to Europe by sea, especially the Central Mediterranean one, account for the highest number and proportion of unrecovered bodies after a shipwreck, according to the IOM. This means that at least one of every two individuals who die remain unrecovered.

In fact, the vast majority of bodies washed up in the sea towards a country like Italy - a major recipient of migration in southern Europe - are also never investigated, and studies show that between 1990 and 2013 only around 22 percent were identified.

Local authorities also tend to ignore cases in which personal belongings such as credit cards and phones are recovered and make investigating easier.

"Europe has now the highest number of death and missing migrants in the world. And it’s probably the highest number of missing people since WWII and the Balkan conflicts. This is huge," said Kathryne Bomberger, director general of the International Commission on Missing Persons (ICMP), in a conversation with FairPlanet.

Most of the missing persons reported by the MMP in the Mediterranean are presumed dead, and their bodies are believed to be lying at the bottom of the sea. Some individuals have washed ashore and been laid to rest in unmarked graves, while a small fraction are still alive, often found in detention facilities or residing within European countries.

The families and close circles of these missing persons must cope with an 'ambiguous loss': complete uncertainty over the fate of their loved one.

"Grief is hard enough, but grief when you don’t know what happened to the person means some days you hope they are alive, some days you think they are dead," Black from IOM’s Missing Migrants Project noted.

Profound sadness, sleep disorders -including dreams and nightmares of the missing person-, anxiety, hypervigilance, the feeling that life has stopped and general memory and physical health issues are all well-documented problems afflicting loved ones of missing migrants.

This situation can also give rise to family conflicts due to factors such as feelings of guilt surrounding the disappearance, disagreements regarding the person's fate, self-isolation and obsessive preoccupation with the missing individual. The absence of the missing person may also necessitate changes in family roles, further contributing to tension and difficulties.

The impact of these circumstances can be particularly detrimental for women, who often face additional challenges stemming from social stigmas and legal barriers that impede their ability to address the situation effectively.

"A lot of aspects of families’ lives are frozen," Marbeau noted. "For instance, there will be administrative [issues], such as not being able to access bank accounts if the person who disappeared was the holder, or there will also be a married woman who won’t be able to be considered a widow and remarry."

"There is going to be poverty issues [due to problems with] inheritance. Sometimes the person [who disappeared] was the breadwinner of the family," she further stated, adding that in certain instances, families may find themselves in debt as they undertake financial obligations to support a family member's journey.

"The families of the missing are often the invisible victims of migration."

Organisations active in this field argue that due to the magnitude of the crisis of missing persons in the region, European states, with the support of the EU, should work together, establish joint guidelines for action and create a shared database to deal with such cases.

"There needs to be a common strategy, with EU backing, to take it seriously," Bomberger said.

The first step European states should take in cases of shipwrecks, they argue, is to deploy greater efforts to quickly retrieve bodies at sea and objects that can help in an investigation. The identification of bodies of missing migrants may be possible by making use of all available tools: DNA samples, body markings such as teeth, photographs, personal objects and, when possible, the collaboration of survivors.

To this end, these same organisations emphasise that it is crucial that states involved in the investigation work towards putting the families of missing migrants at the centre, both to assist in the probe and to offer them some form of closure.

"There are cost-effective ways to address the issue using advanced technologies like DNA and data systems. There are ways, but one has to show political will," Bomberger noted.

The process of addressing these tragic situations is often impeded by numerous challenges. Difficulties arise when attempting to recover bodies at sea, as they may be in a deteriorated state or remain inaccessible in deep waters. Moreover, obstacles emerge when trying to establish contact with families, particularly if they are in irregular situations or reside under authoritarian regimes.

Some argue that the funds that would be utilised for searching, identifying and supporting the families of missing migrants could be better allocated towards preventing irregular migration or providing assistance to those who have successfully reached southern Europe.

The application of international law in cases of dead or missing persons who are migrating is still the subject of some debate. But European states have an obligation to protect the right to life, which is why human rights advocates argue they should investigate and provide information to families just as they do in cases of war and humanitarian disasters.

In this context, human rights defenders, academics and organisations working on the issue maintain that southern European states and the European Union remain unprepared to deal with the gravity of the crisis due to a lingering policy vacuum, minimal resources and cooperation and lack of systematic and effective investigations that include families.

In some instances, efforts can pay off. "Not all missing migrants are dead," said Marbeau of the ICRC, which has a programme for tracing missing persons. "Sometimes families have been looking for each other for years before being able to reconnect."

Marbeau noted, however, that expectations have to be managed carefully. "We know that the search for missing persons in some cases can lead to a dead end, or that it can take years and find out the person is deceased and that the body won’t be found."

To address the ongoing crisis of missing migrants in the Mediterranean, human rights groups advocate for southern European states, with support from the European Union, to establish safe arrival passages. They propose the abandonment of ad hoc search and rescue and disembarkation operations in favor of implementing consistent and predictable practices that prioritise saving lives and preventing further disappearances.

These efforts, they claim, should go hand in hand with an end to the criminalisation of rescue work carried out by NGOs operating in the Mediterranean, in parallel with more concerted action to dismantle criminal people-smuggling networks.

"The first thing is to help prevent these disappearances. And part of this prevention is also to be aware of the humanitarian impact of [European] migration policies," Marbeau said.

Image by Brainbitch.

By copying the embed code below, you agree to adhere to our republishing guidelines.