- About

- Topics

- Picks

- Audio

- Story

- In-Depth

- Opinion

- News

- Donate

- Signup for our newsletterOur Editors' Best Picks.Send

Read, Debate: Engage.

| June 22, 2022 | |

|---|---|

| topic: | Arts |

| tags: | #art, #Brazil, #conservation, #pollution |

| located: | Australia, Austria, Brazil, USA, Hong Kong, Sweden, Spain |

| by: | Abby Klinkenberg |

Bringing together 25 artists from around the world, Points of Return is the latest project initiated by A La Luz, an artistic venture co-founded by environmental artists David Cass and Gonzaga Gómez-Cortázar Romero that aims to provide a platform "for sustainable and environmentally focused creative works."

Thrilled by the quality of artistic work and delighted by its warm reception, they describe Points of Return as "the pinnacle" of their seven-year collaboration. The exhibition, which follows six themes - Ground, Heat, Retreat, Eclipse, Root, and Return - "explore[s] wide-ranging aspects of the climate emergency, offering commentary and creative nature-based strategies."

FairPlanet sat down with six of the contributing artists to consider the way their works shed light on shifting environmental scales, the plurality of knowledges and instability of the human-nature binary.

Participants:

FairPlanet: Climate change is happening on a geological scale, which is something really difficult for human beings to conceptualise. Much of your work brings that complexity down to something that we can process. Could you describe the importance of bridging these scales?

The Western imaginary also understands nature as fixed and infinite when it's actually always changing and in flux. How do you engage with these themes?

Miguel Sbastida: The natural variability of climate - the architecture of climate over the last million years - has totally changed in just two, three generations. It's happening in delayed timescales that we perceive as fixed. Within Western perspectives, we are very used to looking at things as passive, inert or inactive. Western science needs distance between subject and object, between observer and object, between active and passive. So there's this conceptual distancing between the human and the non-human that separates what we consider inner and outer, part of our bodies and outside of our bodies.

In reality, we are entangled in these fluctuating processes: we are part of the hydrosphere, we are part of the atmosphere, we are constantly exchanging matter with these bodies that surround us. We don't really pay attention to those things.

With my work, I try to blur the boundaries between what we consider inner and outer - between what we consider body and environment. If we are capable of blurring these boundaries, then we work within a more eco-feminist, horizontal ontology. We think more ecologically and less ego-logically. This pyramid of hierarchy is broken when we think of the outer as the inner - when we think of the world as an extension of our body.

"We are part of the hydrosphere, we are part of the atmosphere, we are constantly exchanging matter with these bodies that surround us."

Adam Sébire: I agree. Dealing with other scales decenters us and gets us away from the primacy of homo sapiens as epitomised by this horrible term "anthropocene." It moves us towards putting us in our true place and scale: we're at the top of the food chain as humans, with a subsection of our species in the West causing more damage in the last 300 years than the last 300,000 years that humans have been around.

In my thermographic work, a biological and climate scientist trying to reconcile herself with the disappearance of species says, 'Well, humans are at the top of the food chain. Humans can disappear and homeostasis will recover.' That's the way she deals with it - rather fatalistic. But the bridge between these scales, if one is possible, needs to allow our hunter-gatherer brain to move beyond its fight, flight or freeze response and look beyond the horizon - beyond the next day or the next year.

One argument that's been made is that we're not cognitively endowed to cope with such a complex problem because the cause is dislocated in time and space. This light bulb I switched on this morning to illuminate me somewhere in Australia causes a coal-fired plant somewhere over there to generate just a little bit harder, which produces a little bit more carbon dioxide, which sometime in the future might end up over Antarctica, which might give the Thwaites Glacier its final push, etc.

These kinds of time and space dislocations are very difficult for our brains to get around. I see my work as mostly about making these imperceptible perspectives perceptible.

What kinds of things do we miss when we only look at the natural world from a scientific perspective? How does your work bring attention back to those aspects?

Evalie Wagner: You can look at plants from different perspectives: you can look at them from the perspective of a botanist or a doctor, for example. Mine is more like that of a designer: I look at plants in terms of their different shapes, appearances and colors. With this installation, I wanted to open other people's eyes to the nature they have in front of them. It's mostly about opening the senses to create empathy.

I think you need to be emotionally involved to care about anything, including the environment. My aim is to do something with nature and make an artwork out of it - to create something that can maybe open some peoples' eyes.

Some people need research or data to be engaged with something, others need shapes and colors. I understand my installation as a very open and transformative phase. It illustrates the complexity of attempting to comprehend nature with the mind alone. It's always about leaving a question and answering some at the same time. Leaving a door open.

"I think you need to be emotionally involved to care about anything, including the environment."

Felipe de Ávila Franco: Stepping back from the scientific perspective is very important, but it's not enough given our current state of struggle in terms of politics and the environmental crisis. The scientific perspective is able to give us the dimensions of the issue, but it will not cover the vast amount of non-measurable aspects of the manifestation of reality, human perception or the relationship between human and non-human entities.

There's a long history of exploitation of the environment as a resource, which led to the invasion of territories, the extermination of populations and cultures and ongoing colonisation processes around the world. If we consider the individuals and cultures that are not included in what we call "modern" or "civilised" society, we will relate differently to the world. Those individuals and cultures have been relating to the world successfully for much longer than we have related to the world through a scientific lens.

In Western 'civilised' society, what we produce is not only the marginalisation of those cultures and individuals, but we neglect and discredit their perspectives regarding the relationship between human and non-human species. And that is not smart. We literally exterminate knowledge that will be imperative for us to recover our relationship with the Earth.

As artists, we carry this diplomatic passport that allows us to transit almost freely among different fields of knowledge: scientific, spiritual, fiction, legends, common sense, etc. My work considers the possibility of art as a mechanism to awaken new perspectives of knowledge.

The nature-human binary is clearly unstable. We are increasingly recognising that we are in an active relation - in which agency flows both ways - with the natural world. How does your work interrogate that binary and cultivate more reciprocal ecological relationships?

Ulrika Sparre: This striving to connect back to nature is, of course, a constant struggle. In terms of our existential relation to climate change, I think about the anthropocene: How do we accept the fact that we are here? We want to be hopeful, but we also may have to accept the fact that we're going to die. As Adam said, the Earth will recover once we're gone. Maybe that's something we also have to talk about regarding the ground.

In my field recordings, I also, in some way, see the scenery as a future - as a possible future landscape. In Death Valley, in the heat, I'm walking around trying to find something there in this dead land. Those people who arranged stone circles in ancient Darmstadt were trying to connect to nature by reading poetry, but we're sort of left with these electronic devices. We have contact microphones and mobiles and that's how we're trying to connect with nature. How do we do it, you know?

"The Earth will recover once we're gone. Maybe that's something we also have to talk about regarding the ground."

Tanja Geis: For the past few years, I have avoided the word "nature" altogether because it's so problematic and broad. A little while ago, I looked into the etymology of "nature" and it has meant a vast, vast amount of different things. I think the most dominant understanding of it stems from a monotheistic, Christian history, where this monotheistic God created nature as a resource for humans.

That sort of spelled the beginning of the ecological crisis: we feel like we have permission to do as we wish with living things and minerals. It feels hard to use that word when I know its source, and that, in some ways, it created the foundation of our current ecological crisis. It also allows for shorthand that prevents us from becoming intimate in a much deeper way with the species that we live with in the habitats around us.

In my work, I strive to set up either interactive situations or images that show you things that you've seen before, but make them sort of beautiful and strange - which usually refers to a background story of some disturbance that we've caused to our environment.

Just like we build good relationships with people, we need to learn how to listen and how to witness. We need to learn how to be humble. I think that's the path if we want to be able to share this planet in some sustainable fashion.

This transcript has been edited for clarity and concision.

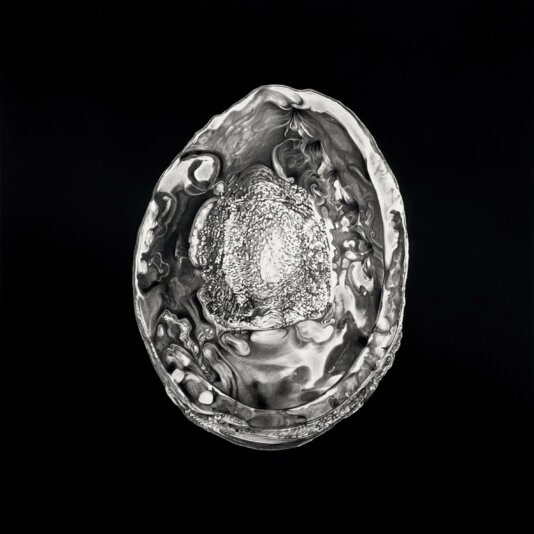

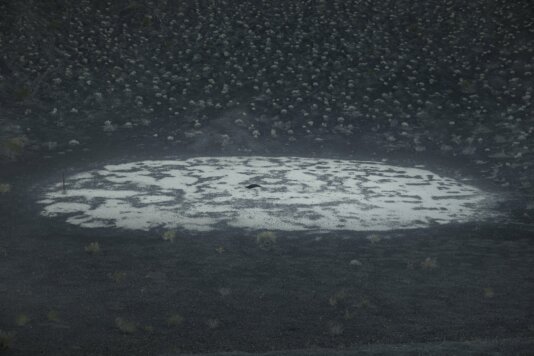

Image by Ulrika Sparre.

By copying the embed code below, you agree to adhere to our republishing guidelines.