- About

- Topics

- Picks

- Audio

- Story

- In-Depth

- Opinion

- News

- Donate

- Signup for our newsletterOur Editors' Best Picks.Send

Read, Debate: Engage.

| December 13, 2021 | |

|---|---|

| topic: | Conservation |

| tags: | #fungi, #mushrooms, #conservation, #food security, #food scarcity, #industrial agriculture, #climate crisis, #climate change |

| by: | Gerardo Bandera |

The Society for the Protection of Underground Networks, or SPUN, is a newly-formed organisation that seeks to map fungal networks and advocate for their preservation. Understanding how closely linked our well-being is to that of these networks, SPUN proposes that we promote and protect them as public goods.

Justin Stewart, one of SPUN’s core collaborators and a researcher at the Kiers Lab in Amsterdam, spoke to FairPlanet about the fungal networks and why we should protect them.

FairPlanet: Can you give us a brief explanation of what fungal networks are and what function they have?

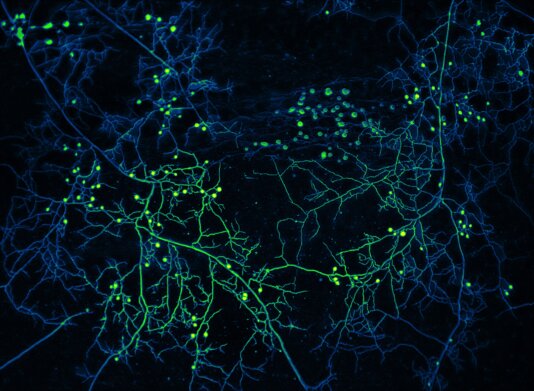

SPUN: A fungal network is a collection of cells, called a mycelium, that interacts with about 90 percent of plants on earth. They explore the soils around them, looking for resources that they trade with plants: nitrogen and phosphorus in exchange for carbon. The diversity of fungal networks below ground seems to determine the diversity of plant species above ground through a symbiotic relationship that’s over 450 million years old. The phosphorus that’s in your food has most likely gone through a fungal network.

We constantly hear about the need to protect or restore the ozone, forests and oceans in an effort to reduce the rate of climate change; why should we add the underground networks to our priorities?

It’s important to think about what these networks are doing: firstly, plants absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and, through photosynthesis, make sugar from it; but the sugar isn’t only used to build the above-ground structure: up to 30 percent gets tunneled down to the roots and is even funneled into these networks. So you can think of these fungal networks as carbon vacuums since they reduce the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere by storing it underground. Reducing CO2 levels is crucial for reducing climate change, but we are not protecting these carbon vacuums - we’re not covering land, we’re not using compost and we’re using fertilisers that kill them.

What human and natural activities degrade the health of soil and the underground networks?

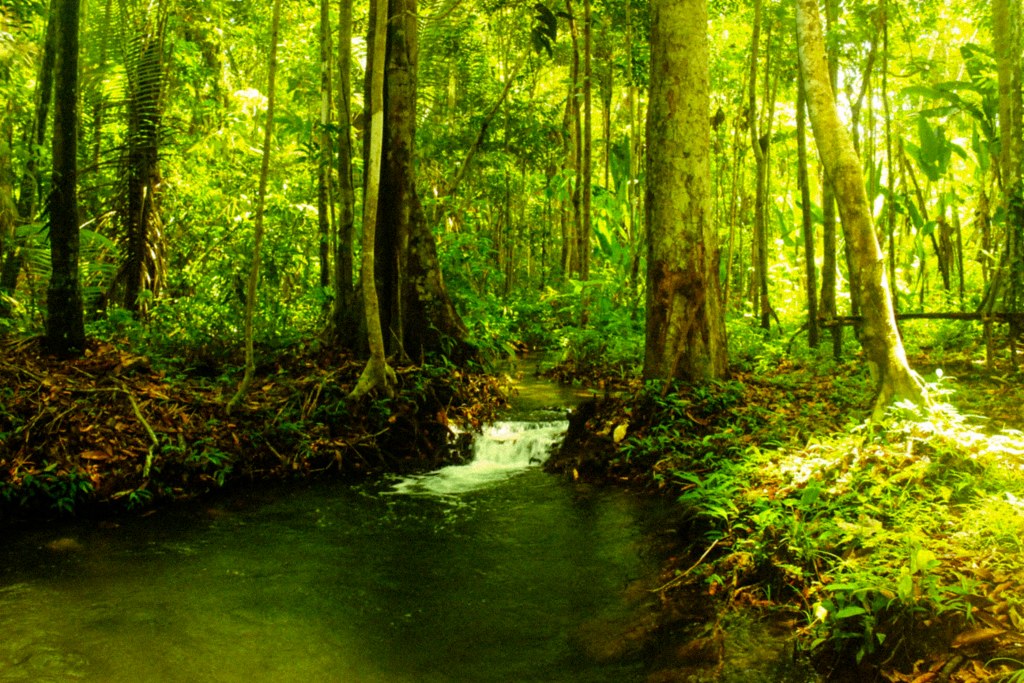

It depends on what scale we’re talking about, but a large one is the industrialisation of agriculture. We’re tilling up land, and if we think of a fungal network as a string, what industrialised farming does is cut the string and break the network. Wildfires are also destroying them; they kill about 95 percent of fungi in the area. And while wildfires can be beneficial, if they occur frequently, as they did in Australia last year, then they are not preserving biodiversity and are destroying the environment. We also need to keep our soil covered. If you think about the soil in cities, there is a lot of uncovered soil, which is free land that could be used for plants to interact with fungal networks to remove carbon from cities - which is really important since cities are hotspots for carbon dioxide emissions.

It’s estimated that by 2050, 90 percent of the world’s soil, which houses these fungal networks, will be degraded. What consequences could this have for humans?

As these fungal networks are destroyed, the carbon they were storing could be released into the atmosphere - further inducing climate change. It may also be more difficult to produce food since many plants heavily rely on this symbiosis for nutrients.

It sounds like this is where SPUN comes in - what are the organisation's missions and priorities?

Our mission is to find these networks, map them, advocate for their protection and work with global and local communities to preserve them. We’re using machine learning and hundreds of layers of geospatial networks, as well as future climate scenarios, to figure out which networks are the most at threat. It’s important to understand which networks are important carbon sinks and which are at highest risk.

We’ll engage with conservancies for their preservation, but also with local populations where important networks are located because some are in places where there might not be the resources or infrastructure needed to protect them. Our effort is to work with these communities, not tell them what to do. We’re making sure we’re doing this in a socially just manner.

Tell us about the team - who is involved with SPUN?

So many people from different career stages. Michael Pollan, the pioneer journalist on food and agriculture and Jane Goodall, the groundbreaking conservationist, are helping to advocate for SPUN. Rose Marcario, the former CEO of Patagonia and Mark Tercek, former CEO of the Nature Conservancy are two of our founding board members.

But the members who will be most active in the work are Dr. Toby Kiers and Dr. Colin Averill, who are leaders in the fields of mycology and ecology. Our team of Science Advisors are the world experts on mycorrhizal fungal networks. And our team of core collaborators, like myself, contribute our research and make the global maps of important hotspots to protect.

One of SPUN’s principles is open data. Who could this growing database of fungal networks interest?

The data is open for whoever wants to use it, from NGOs to researchers to artists to the local communities themselves who want to protect their regional biodiversity.

How can people get involved?

At a larger level, it’s important to have conversations about fungal networks to build awareness of their importance, as well as to advocate for their protection when implementing green policies and local conservation initiatives.

In terms of individual efforts, people can make sure to cover their soil with compost, leaves or plants to provide a resource for the networks to interact with, which keeps them alive. You can also try to buy food locally from farms that are not using industrial agricultural methods, like tilling land - and SPUN acknowledges that not everyone has the means to do this so whatever contribution you can make is great. Our website also has information on how you can sponsor a myconaut or help us map the global underground.

Image by Victor Caldas

By copying the embed code below, you agree to adhere to our republishing guidelines.