- About

- Topics

- Picks

- Audio

- Story

- In-Depth

- Opinion

- News

- Donate

- Signup for our newsletterOur Editors' Best Picks.Send

Read, Debate: Engage.

| October 23, 2021 | |

|---|---|

| topic: | Death Penalty |

| tags: | #women's rights, #death penalty, #Africa |

| located: | Zambia, Botswana, Zimbabwe |

| by: | Cyril Zenda |

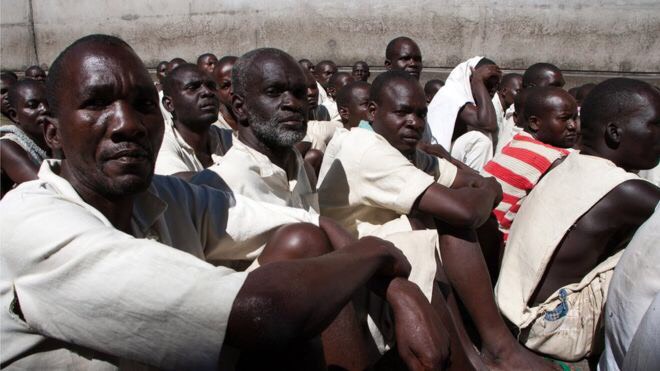

Miriam Chilosha is a death row prisoner in Zambia, having been sentenced to death by hanging last year for burning her boyfriend to death after a dispute. She was one of the 24 women who were on the southern African nation’s bloated death row of 495 at the beginning of the year when former president Edgar Lungu commuted the sentences of 246 of them (21 females) to life in prison.

Those unfortunate not to benefit from the Presidential clemency order have good reason to be relieved that the new Zambian leader, Hakainde Hichilema - a former regular prison inmate - has a soft spot for prisoners.

With Zambia being an abolitionist-in-practice state - meaning that although capital punishment still exist, it has not carried out for ten or more years - there is still no copper-bottomed guarantee that those on the death row would not end up at the gallows.

Since this position is not codified in law, any new leader may decide to sign their death warrants, just as the country’s second president Frederick Chiluba (1991-2001) did in 1997, when he sent eight inmates to the gallows, some of whom had been on the death row for decades.

For as long as Zambia has not abolished the death penalty and judges continue to hand it down, thoughts of her ending up at the gallows would continue to haunt Miriam and her fellow female death row inmates at Mukobeko Maximum Prison.

“I witnessed the last execution in January 1997 when I myself was a prisoner,” Godfrey Malembeka, the executive director the Prisons Care and Counselling Association (PRISCCA), a non-governmental organisation that works to alleviate the plight of prisoners in Zambia, told FairPlanet.

"This is one of the things that necessitated the formation of PRISCCA by a group of prisoners in 1997," he added. "When the organisation was officially registered in the year 2000, we started advocating for the abolishment of the death penalty among other advocacy issues in Zambia. This was not a pleasant exercise and many organisations shied away from it but we had to do it. We met President Levy Mwanawasa [2002-2008] when he visited Mwembeshi Open Air prison and raised our concerns on the death penalty in Zambia."

"As you may already be aware, President Mwanawasa is the first Zambian president to declare a de facto moratorium against the death penalty after he refused to sign any death warrant during his reign," Malembeka further stated. "Successive presidents have upheld the moratorium since then. This is a welcome move, however we are also alive to the fact that this pronouncement is not backed by any law. This means any president can execute if they so wish."

Malembeka’s fears are not unfounded, as this has happened in neighbouring Botswana, where a new president, Mokgweetsi Masisi, made signing death warrants priority after his election in October 2019.

As human rights campaigners marked World Day Against Death Penalty on 10 October under the theme “Women and the Death Penalty," the focus was on women who risk being sentenced to death, who have received a death sentence, who have been executed and those who have had their death sentences commuted, exonerated or pardoned.

It was a moment for activists to highlight how prejudices, stereotypes, discrimination, inequality and other factors contribute to placing some women on the death row. The activists say that even where women are not on the death row themselves, capital punishment still affects them.

"In fact our law [in Zimbabwe] does not permit the execution of women, but women and children suffer terribly nonetheless," Veritas, a legal and legislative watchdog that is spearheading the abolition of the death penalty in Zimbabwe said in a statement to FairPlanet. "If their husbands and fathers are executed they are deprived of family life and income, and are often stigmatised or even ostracised by their communities."

In Botswana, activists marked the event - which coincided with the 20th anniversary of the 2001 hanging of the first-ever white person in the country, Mariëtte Bosch, a South African national convicted of killing her love rival - by imploring their government to stop the executions.

"Botswana remains the only country in Southern Africa which still carries out executions," noted Ditshwanelo - The Botswana Centre for Human Rights, in a statement to mark the day.

"The execution affects everyone. Children face the psychological trauma of knowing that their mother has been executed and that they will never see her again. These children are sometimes rejected because of societal stigma even though they are in need of psycho-social support, care and assistance."

While the real hope of Miriam and her fellow female death row inmates in Zambia lies in abolition, it is not always the case for their male counterparts, especially those coming from privileged backgrounds.

In 1991, Kambarage Kaunda, the son of then-president Kenneth Kaunda, was sentenced to death for murder, but he managed to get the charges and conviction squashed on appeal as he could afford to hire an army of lawyers to mount a sustained legal warfare to get him off the noose.

These are some of the structural inequalities that activists say female death row inmates, especially those in Africa, suffer from.

"Discrimination based on sex and gender, often coupled with other elements of identity, such as age, sexual orientation, disability and race, expose women to intersecting forms of structural inequalities," said the International Federation for Human Rights (FIHR). "Such prejudices can weigh heavily on sentencing, including when women are stereotyped as an evil mother, a witch or a femme fatale. This discrimination can also lead to critical mitigating factors not being considered during arrest and trial, such as being subjected to gender-based violence and abuse."

Claims of prejudice resulting from the profiling of victims of the death penalty are not unfounded, as they have been proven in most cases where the punishment has been widely meted out.

Dr Dior Konaté, a professor of African history at South Carolina State University in the United States who has researched the application of the death penalty in colonial Africa, says that stereotypes and prejudices always worked against the victims.

“The death penalty was deeply rooted in racism,” wrote Dr Konaté, who is the author of Prison Architecture and Punishment in Colonial Senegal and is currently working on a book titled Constructing Death: Capital Punishment in Colonial Senegal.

“It was politicised and weaponised as colonial administrators targeted and profiled particular ethnic, religious or political groups as potential capital criminals or suspects," continues Konaté.

"Colonial judges built their prosecutions on the characters of African defendants rather on the circumstances of the crimes they had committed. Racist stereotypes and prejudice created the ground for the criminalisation of activities such as witchcraft and cannibalism. Colonial judges severely prosecuted these crimes, which stood as evidence of the so-called 'savagery' of Africans, legitimising the necessity of the French’s 'civilising mission' in Africa."

Among the various structural inequalities that most women in Africa suffer from is that in addition to being poor, most are less educated compared to their male counterparts, which makes them especially vulnerable to manipulation.

While globally women make about five percent of death row prisoners, and African women may not be at very high risk of execution at home, poverty has seen hundreds of them appearing on the death row in China after being lured and or tricked into being drug mules.

Past Chinese media reports have suggested that 80 percent of foreigners arrested for drug trafficking were Africans. For example, while under Zimbabwe’s Constitution women are exempt from the death penalty, in 2018 the government revealed that 11 of the 12 Zimbabweans who were facing the death penalty for drug trafficking in China were women.

Other countries on the continent have also found themselves in similar situations, in which their female citizens faced death sentencesin China, where thousands are executed by firing squads annually.

A total of 108 countries in the world have abolished the death penalty for all crimes.

More than half of the independent nations in Africa - 30 out of 54 - have completely abolished the death penalty, with Sierra Leone and Malawi doing it this year.

Only three - Botswana, South Sudan and Somalia - have recently carried out an execution. Some 28 countries worldwide are abolitionist in practice, meaning they have not executed anyone for at least 10 years. Another 56 countries are still retentionist, but this figure is being reduced.

Image by Dany Fly

By copying the embed code below, you agree to adhere to our republishing guidelines.