- About

- Topics

- Picks

- Audio

- Story

- In-Depth

- Opinion

- News

- Donate

- Signup for our newsletterOur Editors' Best Picks.Send

Read, Debate: Engage.

| April 23, 2021 | |

|---|---|

| topic: | Refugees and Asylum |

| tags: | #Rwanda, #Zimbabwe, #genocide, #refugees, #UNHCR |

| located: | Rwanda, Zimbabwe |

| by: | Cyril Zenda |

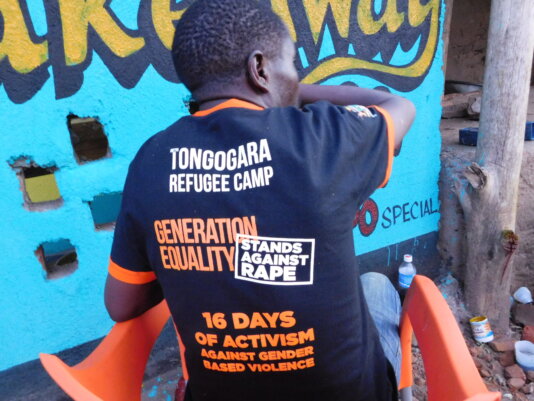

“This is now my home,” declared Henri, a 48-year old Rwandan national at Tongogara Refugee Camp some 420 km southeast of the capital Harare. “A home is a place that is safe for someone so I have no other home [country] to go to because it is only here that I am safe,” he added apropos his decision to remain in the country long after his welcome had been spent.

This April marked 27 years since the 1994 Rwandan genocide in which more than one million people, mostly ethnic Tutsis and moderate Hutus, were killed. This greatest human tragedy in living memory resulted in hundreds of thousands of Rwandans fleeing to many neighbouring countries and even further afar, where most of them have continued living as refugees.

Henri, together with about 150 others form a remnant of Rwandan refugees that are still living in the refugee camp eight years after the United Nations Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) invoked the Cessation Clause on 30 June, 2013, which declared Rwanda safe for its citizens living as refugees across the world to return. The clause applies to those who fled the country between 1959 and December 1998.

Under this Clause, United Nations member states hosting Rwandan refugees are enjoined to comply with the declaration, but realities on the ground have always made the implementation of the Clause difficult, as most of these refugees, just like Henri, have been resisting repatriation.

Most of these refugees from the Hutu tribe have never trusted Paul Kagame, the thoroughly feared Rwandan president who stands accused of heading one of the most brutal regimes on the African continent. Kagame, who is credited with ending the genocide, is a Tutsi.

Even after the December 2013 deadline had been extended by two years to December 2015, most of these Rwandans have refused to budge, insisting that their country is not safe for them.

The UNHCR has in the past conducted “go-and-see” tours for some of these refugees to Rwanda, to help them make informed decisions, but those returning from these visits have alleged hostile reception back “home”, thereby emboldening their resolve never to return.

In 2017, the Rwandan community leader at Tongogara Camp, Philip Sindayigaya, indicated that all of the 500 Rwandans who were living in the camp at the time preferred integration into local communities to repatriation.

“We have been appealing for Zimbabwean citizenships, we have noted that other nationals have benefited or resettled and we want similar treatment,” the local media quoted Sindayigaya as saying. “You should know that every Rwandan here ran from different problems back home, but the UN is generalising our problems…. there are still problems in our home country and as I speak more people are still seeking refugee elsewhere.”

At the time the UNHCR invoked the Cessation Clause, there were thousands of Rwandans living in the camp. Since the threat of forced repatriation has been looming over their heads, some of these refugees, like Philip Gasamagera (53), have over the years moved away from the refugee camp to start life in Harare and other urban centres. This has seen the Rwandan refugee population in the camp progressively dwindling to the present figure of about 150.

In December last year, Johanne Mhlanga, an administrator at the Tongogara refugee camp, told visiting Parliamentarians that funds were being sought to repatriate over 800 refugees from more than a dozen countries, although Rwandans were not eager to return home.

The genocide and subsequent civil wars forced more than two million Rwandans to flee the country. While over the years many have voluntarily returned home, hundreds of thousands others like Henri and Gasamagera vow never to set foot in Rwanda again.

About 270,000 Rwandan refugees from the 1994 genocide remain scattered in about a dozen major African refugee host countries: Angola, Burundi, Cameroon, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Kenya, Malawi, the Republic of Congo, South Africa, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

Because of this resistance, which has seen both the 2015 and the 2017 deadlines being ignored, most of the host governments are left with no option but to let the Rwandan refugees continue to live in their countries even when their status has become vague following the decision of the UNHCR to invoke the Cessation Clause.

These host nations are also bound by the international human rights principle of non-refoulement, which precludes them from forcibly repatriating refugees back to home countries where they could face torture, cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment and other irreparable harm.

Mozambique, which has more than 2,000 Rwandan refugees, has in the past made clear its continued compliance with the 1951 Geneva Convention relating to the status of refugees - specifically the commitment not to repatriate refugees against their will.

Other countries like Zambia, which is home to more than 4,000 Rwandan refugees, have started integrating them into their own societies after realising that they would not get them to agree to repatriation.

The refusal of Rwandan refugees to repatriate is the subject of a book titled “Post-genocide Rwandan Refugees…Why They Refuse to Return ‘Home’: Myths and Realities” by Masako Yonekawa, a UNHCR field worker in the DRC. The book highlights the repeated refusal of post-genocide Rwandan refugees to return ‘home’, and why even high-profile government officials continue to flee to this day.

“This resistance has taken place for a lengthy period in spite of the fact that genocide ended (over) 25 years ago and the government of Rwanda and the United Nations have assured security in the country,” wrote Edward Newman, a professor at School of Politics and International Studies at the University of Leeds in a review of this book. “Based on interviews conducted with a number of refugees living in Africa, Europe, and North America, the book explains the high degree of fear and trauma refugees have experienced in the face of the present Rwandan government that was involved in the genocide and other serious crimes both in Rwanda and the neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo.”

Kagame’s alleged brutality was also captured in a book titled Do Not Disturb – The Story of a Political Murder and an Africa Regime Gone Bad, written by journalist Michela Wrong.

Based on testimonies from key participants, Wrong uses the story of the murder of Patrick Karegeya, once Rwanda’s head of external intelligence, in a Johannesburg hotel room, to explore the creation of a modern African dictatorship.

Kigali, however, denies the dictatorship allegations levelled against Kagame. The defenders of the regime insist that only the guilty have good reasons to avoid returning home.

“Some of the refugees were tried in absentia and convicted by the Gacaca semi-traditional courts for their role in the genocide against the Tutsi in 1994 in Rwanda, while others are fugitives yet to be put on trial,” wrote The New Times, a pro-government Rwandan daily.“This group, according to previous testimonies from different refugees, has played a key role in discouraging the repatriation process, for they fear being brought to account for their crimes. They have instilled fear in some of these refugees feeding them lies that they would be persecuted once they repatriate.”

Image: World Economic Forum.

By copying the embed code below, you agree to adhere to our republishing guidelines.