- About

- Topics

- Picks

- Audio

- Story

- In-Depth

- Opinion

- News

- Donate

- Signup for our newsletterOur Editors' Best Picks.Send

Read, Debate: Engage.

| July 12, 2022 | |

|---|---|

| topic: | Renewables |

| tags: | #USA, #solar power, #California, #renewable energy, #droughts |

| located: | USA |

| by: | Frank Odenthal |

In California, climate change is already a reality. Annual devastating wildfires, years-long droughts and over-pumped groundwater systems are symptoms of the onset of a global environmental catastrophe.

Researchers worldwide are desperately looking for ways to avert the worst-case scenario and, should it already be too late, deal with the new environmental challenges in the most effective way possible.

The Solar Canal Project, a kilometer-long network of irrigation canals in California which will be used to generate renewable energy, is emerging as one promising solution to these challenges.

FairPlanet spoke to Roger Bales, a professor of engineering at the University of California and a researcher on the Solar Canal Project.

FairPlanet: Tell us what the Solar Canal Project is all about.

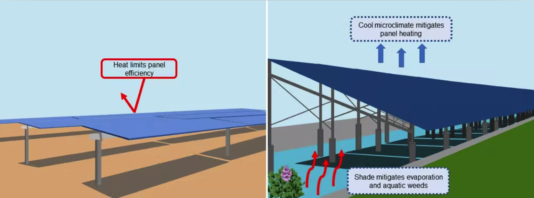

Roger Bales: Putting solar panels over canals is a multi-benefit infrastructure upgrade for these open canals, which are built infrastructure, and we have the opportunity to use them to add on more infrastructure. The multiple benefits include reducing evaporation of water and putting solar panels over already disturbed land rather than taking natural lands or productive farmland out of production.

Also, in California and other places, the canals function as electricity corridors, and so it is very convenient to use their distribution lines to deliver the electricity generated to customers. In some places, the generated electricity may also be used without putting it into the grid.

Another big improvement is that you keep sunlight off the canal to some extent, meaning you have less growth of aquatic weeds and algae. In some places, it‘s very expensive to clean those out. In other places, it causes water quality problems in case the water is used for drinking water downstream. In California, most of the canals are used for irrigation water, but there are a few key ways to deliver drinking water into cities.

Finally, if you evaporate water, it has a cooling effect, which means in this case that the solar panels are getting cooled from the evaporating water underneath, and that tends to make them work more efficiently. That, of course, depends on the material and the technology you use for your solar panels.

What was the inspiration behind the project?

Based on a study we published a year ago showing the economic feasibility of it and evaluating California‘s some 6,500 kilometers of open canals, there is great potential for renewable energy generation using this already disturbed land.

The next step after showing the feasibility was to do a demonstration project, because this hasn‘t been done in California or the US before. It‘s been done in India, and there are a couple of prototypes under development in Europe, but the only ones that have been built that we are aware of are in India.

So we are building a prototype as part of a 20 million Dollar project. Since it‘s the first one, there’s considerable design and planning work, and we‘re doing research along with it. We are partnering with the oldest irrigation district in California, Turlock Irrigation District, which is located in the central valley.

California‘s central valley provides a large fraction of our nation‘s food (over one third of the nation’s vegetables and two-thirds of the nation’s fruit and nuts) and produces a lot of food for export, and so it is an area that needs every bit of water it can get, because we have more land than water for irrigation. Evaporation savings, even if they are small, could be put to use to grow more food.

What is the current situation in California in terms of water scarcity?

All of California has what we call a Mediterranean climate, meaning that our precipitation comes during the cool season - the winter. And summer, the growing season, is quite dry. The average precipitation across California is about two feet, which is two thirds of the global average precipitation. So we have overall a semi-arid climate.

Now, most of our water comes from the mountains because we have these steep precipitation gradients; the water is then captured in the rivers that flow downward, stored behind dams and recharged into groundwater. It is then pumped out or delivered for use in summer. So we get our spring run-off from the mountains as the snow melts and rain runs off.

The situation is that there is more potentially arable farm land that could be irrigated than there is water available. About eighty percent of California‘s water is used for irrigation, and right now we are in the third year of a drought.

In the municipality, in order to cut back the use of water, our governor just issued a mandate that no ornamental grass or ornamental landscaping can be irrigated. And I expect that there will be more restrictions coming.

I suppose this is all a result of climate change?

Yes. The warming temperature has a few consequences: one is that the water falling in the mountains is being used more by the forests, because the growing season is longer with a warmer climate.

The second is that we are getting bigger and more intense precipitation, and we can‘t capture all of that water that comes down at once. So for flood control we have to release it to the ocean.

And thirdly, in the central valley they need more water for growing food crops when it‘s hotter. So it’s both the demand side and the supply side that are hurt during a warming climate, and that‘s our new reality here in California.

Do neighbouring communities support the initiative to cover canals with solar panels?

Yes, so far I think there is good public support. There is some healthy skepticism also, because putting solar over canals costs more than putting solar over an open field. So if you already own the field and you want to plant solar panels instead of crops, you don‘t have to buy the land. But if you first have to buy the land, that‘s a huge cost.

There‘s also some great support from the conservation community, which is quite strong in California, because we are not taking natural lands and converting them into infrastructure. We want to set aside 30 percent of our land and our coastal waters by 2030 for its biodiversity value. This was initiated by the United Nations as a thirty-by-thirty-initiative.

California governor Gavin Newsom and President Biden have also made this 30 x 30 pledge. Right now, California is at about twenty four percent of conserved land to meet the 30 percent 2030 goal.

Can you share some figures about the proposed impact of the project?

I don‘t have the numbers for our prototype project yet, because it‘s still in preliminary design. But if we were to cover all of the canals in California, we estimate that would provide thirteen gigawatts of electricity generating capacity, which is about half of what California needs to meet its 2030 goals for renewable energy.

In addition, according to our study mentioned above, 63 billion gallons of water would be saved from evaporation annually, if we‘d cover all the canals. That‘s enough water to irrigate 50,000 acres of farmland. It‘s also enough to service a city of two million people for a year. With this prototype, for a start, we‘re doing just two or three miles.

Are these canals owned by the government or are they private property?

They are owned by public agencies. We have two very large canals that run from the Sacramento Delta to San Joaquin Delta, which is where all the rivers flow into from the Sierra Nevada mountains, and those canals run down to south-coastal California, to Los Angeles and San Diego.

Those canals are 150 to 200 feet wide and provide water to the municipal users as well as some irrigation. That‘s about ten to fifteen percent of our canals owned by the state or federal government for those larger uses. Then we have plenty of irrigation districts, which are special districts that were formed mainly to provide irrigation water to farmers and local electricity.

Are solar panels placed over canals easy to maintain?

Normally, solar panels do not require a lot of maintenance. Hopefully, the rain water washes the dust off them. We don‘t know what‘s going to be the wildlife effect if we get a lot of bird droppings on them, for example.

We don‘t anticipate problems with corrosion or dust accumulation. Our estimates are that solar panels over canals will lower the maintenance needs on the canals. And we just have to design them so that the canal operators can still get the access they need if they have to do some maintenance.

On the smaller canals, you want to design it so that they can get in at least on one side, maybe not on both sides of the canals. For some intermediate-sized canals, access from both sides may be important. For the largest canals, we‘re currently not looking to cover them, because we want to get some experience from the smaller canals first.

Who is running the project and who are you co-operating with?

I‘m a researcher at the project. The University of California is doing the evaluation. The project developer is a start-up company called Solar Aquagrid - they are working in the public interest. They worked with the state to provide the financing for the prototype.

The California Department of Water Resources is funding the project with general revenue from the state, which was approved by the legislature and governor, and Turlock Irrigation District is the operating partner.

How long will it take for the project to be operational?

Right now we‘re in preliminary design, and we hope the construction will start this fall and be completed by the end of the year, but it will probably slip into January or February. We then want to do an evaluation for two years, so that our prototype project will last for another two and a half years.

At the same time, our research will involve developing a scaling strategy that is taking into account what we know now, and then, as we learn things from the prototype, adding that to our evaluation and developing a strategy of what‘s next.

The solar installation that we do now will produce electricity and other benefits for many years. Over the long term, we hope that the expansion of this sort of project can be self-funding, because it will be generating electricity revenues and other benefits. We‘re also looking at how to couple energy storage with solar panels over canals so that the Turlock Irrigation District can put the electricity into their grid when they need it.

Roger Bales is Distinguished Professor of Engineering, University of California, Merced.

Image by Solar Aquagrid LLC, CC BY-ND.

By copying the embed code below, you agree to adhere to our republishing guidelines.