- About

- Topics

- Story

- In-Depth

- Picks

- Opinion

- News

- Donate

- Signup for our newsletterOur Editors' Best Picks.Send

Read, Debate: Engage.

| December 03, 2019 | |

|---|---|

| topic: | Political violence |

| tags: | #China, #Hong Kong, #Uighur Muslims, #human rights |

| partner: | Screen Shot |

| located: | China |

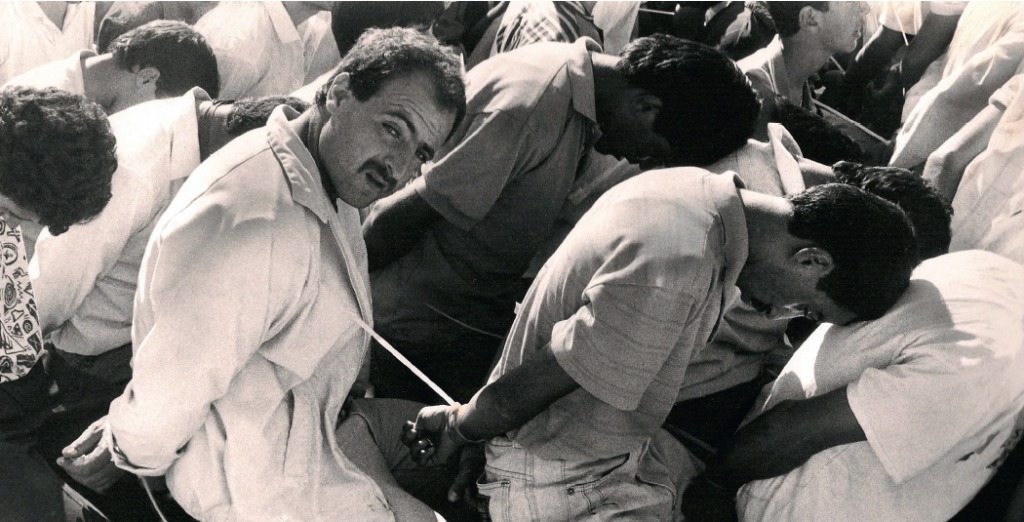

Such reports describe detention and concentration camps holding an estimated one million Uighurs, Kazakhs and other Muslims throughout the province.

Recently, 400 pages of internal government documents were leaked to the New York Times, and last week saw the release of the China Cables, a cache of classified government papers obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ). This Is Not Dystopian Fiction. This Is China reads the New York Times’ headline while the Guardian followed shortly with ‘Allow no escapes’: leak exposes reality of China’s vast prison camp network. The Embassy of China in London immediately responded to the Guardian’s reports: “First, there are no so-called ‘detention camps’ in Xinjiang. Vocational education and training centres have been established for the prevention of terrorism.”

The past few years have seen extreme crackdowns on terrorism and extremism—this often serves as an excuse for ethnic persecution and religious suppression. The Guardian reporters note: “Chinese authorities have split up families, targeted the Uighur language and culture for suppression, razed cultural and historic sites and criticised even mild expression of Muslim identity, micromanaging everything from beard length to babies’ names.”

The wider pattern of disinformation and doublethink is terrifying. The documents obtained and released in translation included answers for questions that authorities were expecting from students returning home from university, only to find their parents gone. Student protests have a long and complicated history in China. “The authorities in the Xinjiang region worried the situation was a powder keg. And so they prepared,” stated one of the many pages leaked.

One of the documents is titled Tactics from Turpan City for answering questions asked by the children of concentrated education and training school students. In it, “concentrated education and training school” is the euphemistic term used to describe the extensive network of indoctrination camps across the region.

“Where are my family members?” returning students are expected to ask. The scripted reply with “They’re in a training school set up by the government to undergo collective systematic training, study and instruction. They have very good conditions for studying and living there, and you have nothing to worry about.”

It’s worth reading through the translated documents in full, but a short extract illustrates the terrifying reality. The word ‘Orwellian’ is generally overused, particularly in recent years, but here it could not be more apt. “Did they commit a crime?” a student might ask. “Will they be convicted?”

The directed response has to be: “They haven’t committed a crime and won’t be convicted. It is just that their thinking has been infected by unhealthy thoughts, and if they don’t quickly receive education and correction, they’ll become a major active threat to society and to your family. It’s very hard to totally eradicate viruses in thinking in just a short time.”

In order to comfort students, camps promise the possibility of arranging video meetings, yet the Chinese Embassy has simultaneously stated that “trainees could go home regularly.” Authorities have promised that the camps offer useful vocational training, yet detainees include scholars, civil servants and entertainers.

This is not what one would expect from an anti-terror campaign; rather, it is what happens when an authoritarian government cracks down on a disenfranchised minority. These documents expose, as the Times put it, “the paranoia of totalitarian leaders who demand total fealty in thought and deed and recognise no method of control other than coercion and fear.”

‘Round up everyone who should be rounded up’ (‘ying shou jin shou’ in Chinese) is a phrase that has seen a resurgence since the appointment of Chen Quanguo to Xinjiang, a new party boss who has been accused of overzealousness in the past. This phrase was previously used to encourage officials to be focused and careful when collecting taxes or harvests. Now, it is being used to describe the mass detention of citizens. “Freedom is only possible when this ‘virus’ in their thinking is eradicated and they are in good health.” This isn’t from ‘1984′—this is China under Xi Jinping.

By copying the embed code below, you agree to adhere to our republishing guidelines.