- About

- Topics

- Picks

- Audio

- Story

- In-Depth

- Opinion

- News

- Donate

- Signup for our newsletterOur Editors' Best Picks.Send

Read, Debate: Engage.

| June 25, 2022 | |

|---|---|

| topic: | Sustainable Development |

| tags: | #Hong Kong, #textile industry, #pollution, #sustainable clothing, #fashion industry |

| located: | Hong Kong, Sweden |

| by: | Chermaine Lee |

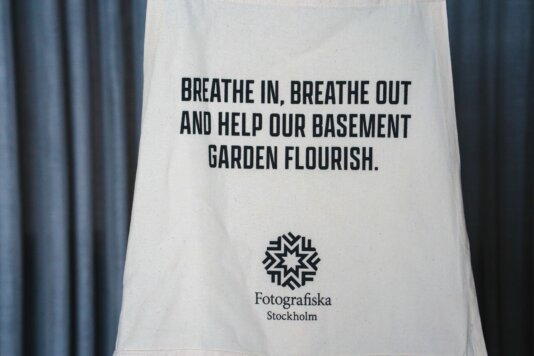

In the heart of Stockholm lies the red-bricked photography museum Fotografiska, which has recently received renewed media attention for pioneering the usage of carbon-capturing aprons in its café. The beige-coloured aprons, H&M Foundation said, could become a game-changer in slashing carbon emissions from the infamously dirty textile industry.

The textile industry is responsible for one-tenth of the world’s carbon emissions - more than the aviation industry - and produces over one-third of the world’s primary microplastics released into the environment amid the burgeoning plastic crisis.

It also accounts for one-fifth of the global clean water pollution from dyeing: producing a single T-shirt requires 2,700 liters of water, equivalent to the amount of drinking water for a person for 2.5 years.

The innovative aprons are part of an ongoing research project of the Hong Kong Research Institute of Textiles and Apparel - CEO Edwin Keh told FairPlanet in an interview.

Having headed the R&D center for over a decade, the textile supply chain expert said the project is born out of the mission to bring a brand-new business model that puts sustainability at the forefront of the fashion industry.

Keh is a godfather figure of Hong Kong’s fashion sustainability industry. This is not Keh’s first endeavour to reverse pollution from the textile industry: the humorous and ardent scientist created technologies that helped fast fashion brands employ recycled fabrics, and engineered the recycling machines in Hong Kong’s rejuvenated textile factory-turned-mall.

He believes that a successful fashion solution should be a business model brands find appealing, instead of a call for charity. The carbon-capturing apron is one of the projects he hopes more prominent fashion brands will take up one day.

FairPlanet: How exactly does this apron capture carbon?

Edwin Keh: We took a look at the existing carbon sequestering technology. We looked into factories that burn coal - how they scrub carbon before it goes into the atmosphere, and the design of their chimney. There’s already tech in filtration and scrubbing. We identified anime - a chemical that attracts carbon molecules out of the ambient environment, and it can stabilise carbon dioxide. We did an experiment to store carbon in cotton. We put anime in a T-shirt, which can efficiently capture carbon.

This coincides with our cooperation with the H&M Foundation. It has an exhibition at Sweden’s museum Fotografiska, which is a large-scale museum in Europe for photography and modern art. At the beginning of this year, we mentioned this project to them. They were interested and asked if we know any ways to release the captured carbon dioxide. This is a project in progress and we haven’t solved all the problems with releasing the carbon dioxide after we capture it or how to sequester it.

What we have learned so far is that we can heat the T-shirt up and the CO2 can be released. This doesn’t change anything because it does capture, but it releases the CO2 later. The [H&M Foundation] said they are experimenting with releasing carbon in a closed environment in their greenhouse.

We experimented with the same idea. We put the T-shirt in a box with a plant inside, and put it under the sun, and then we saw the level of CO2 rise rapidly, when the CO2 was released. Then the plant absorbed the CO2 and we saw [the CO2] drop. The plant used the CO2 to grow in the process of photosynthesis and in the process released some CO2.

We are considering how to sequester the carbon captured in such T-shirts - what if we used the captured CO2 to grow cotton and other raw materials for apparel? Then there’s a net sequestering process as long as we keep the material we grow in use.

[Fotografiska] said they have a greenhouse and so they took the materials to try them out. The known restaurant there has a greenhouse in the basement. They plant their herbs and vegetables there. They said, "how about we use CO2 capturing aprons in the daytime and let the plants sequester them overnight in the greenhouse?" These plants [that capture carbon] become the food for their patrons. [The apron] is only the first half of the project. The material captures carbon, but it will become saturated, so you need to sequester carbon and turn it into a solid or stable state. It’s still an ongoing research; we probably will only finish it next year.How did this idea come about?

About 7-8 years ago, we did an industry survey with over 200 stakeholders [in the textile and apparel industry] in Hong Kong. I asked them three main questions: What are the biggest challenges they face? What is the pinpoint of going forward? And what can Hong Kong do to continue for value creation?

The result was consistent: Sustainability is one of the main focuses - consumers and suppliers pressure them hard in this respect. We did a lot of recycling projects in the following few years - [organising] business-to-customer workshops and educational projects.

In 2019, we arrived at the conclusion that no matter how much recycling we do, we cannot achieve a fundamental change in our industry and it cannot achieve carbon neutrality.

What is 'recycling?' It’s doing fewer bad things. It seeks to stretch the lifespan of current materials and make a second or third use of them to retain their value in the existing economy. Recycling can reduce impact, but it can’t change the circulation. We have to change the industry, which means we have to do more good things.

Can we use new materials and abandon traditional materials? Can we change our business model? Can we launch rental or leasing businesses and change the idea of ownership?

In terms of biodiversity - can we plant cotton? Can we make new cellulose? Can we improve the production process so that the air won’t be as dirty, water won’t go to waste and the soil won’t be polluted? It’s a big research domain. We are looking at planting new cotton and using agricultural waste as raw materials.

Another CO2 absorbing T-shirt we produced is made from recycled cotton 80 percent of the materials are post-consumer waste. We asked ourselves if the waste in the landfill can be turned into clothes. This doesn’t just mean using fewer new materials, but it also finding new sources for raw materials. We recognise that no matter what, carbon emissions occur during the production and transportation processes. That got us thinking - can we look at carbon sequestering?

How does this apron help the environment?

In pre-industrial times, the carbon concentration was below 200 parts per million (ppm), but now it’s over 400 ppm. This T-shirt can capture roughly the equivalent of 1/3 to 1/4 of a tree's worth of of carbon dioxide a day, and it can repeat each day if we release the captured CO2.

The apron was washed over 100 times and it can still capture the same amount of carbon as it did on day one. After two or three capture cycles, the apron can sequester the carbon involved in its production process, which means that in the 4th or 5th cycle it will become carbon negative.

If this can be scaled, there will be a noticeable impact. If you make bedsheets or curtains or other soft surface, it can sequester a larger amount of carbon.

We are looking at how we can sequester carbon in the most efficient way. In Stockholm, luckily, there’s such a beautiful short cycle, but ideally if we can functionalise detergents. We are trying to release the sequestered carbon dioxide in the washing of the material by using a detergent as the carbon release and sequestering agent. If we can turn the captured CO2 into a solid, we have taken net CO2 out of the environment. We think it’s more realistic and efficient, so we still need to do more research on this. We are optimistic we will find a solution.

The process of making the apron has a premium because it involves some chemicals processes - so far we can’t say definitively how much energy or resource we use. In early research findings, we used a basic chemical; we released a video of the whole process. Our estimate is that it doesn’t double or triple its costs in the production process.

There would be an incremental cost due to the chemical and an additional processing stage, but this chemical isn’t expensive.

What are the limits of this innovation in slashing the textile industry’s carbon emissions?

At the end of the day, this is part of the solution, but by no means the entire solution, because its speed and the amount of carbon it can sequester aren't sufficient. There are 50 gigatons of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases that we need to sequester globally to hit the UN climate change goals.

To sequester such a large amount of carbon dioxide and greenhouse gases there must be multiple solutions - including industrial solutions - and they have to be a lot more aggressive than the existing ones. The T-shirt is a consumer engagement, an incremental improvement and a step up.

For the textile industry, we have to change the growth model and reduce our total consumption volume. If you look at the wardrobe of our past generation, it’s a lot smaller than ours. Our consumption volume has increased by a lot, so our concept of ownership has to change in the future. Can we rent, lease and put our wardrobe in the cloud?

"There must be multiple solutions - including industrial solutions - and they have to be a lot more aggressive than the existing ones."

There are many items we don’t necessarily have to own, like cocktail dresses - we wear that once a year, so do we have to own them? Brands need to sell more services other than products: fashion can be a service instead of a product. This type of growth model has to be considered.

New raw materials are also very important - currently, the most commonly-used raw materials in the fashion industry is petroleum-based polyester, which accounts for over 60 percent of all textile production. Petroleum-based products should be reduced or eliminated, and we can focus more on cellulose-based ones or wool [protein-based]. We have to fundamentally change the source of materials.

Even if we focus on cellulose-based materials, we have to think about whether we can source it somewhere else. Can we use agricultural waste? Can we use algae?

Cotton takes up a lot of farmlands and uses a lot of water and pesticides. When our population keeps growing, these farmlands can be better-off growing crops for food consumption rather than materials for clothes. What are some new sources of cellulose? And can we improve the production process so it’s less water-intensive, energy-intensive and chemical-intensive? The whole enterprise and the financial model have to be fundamentally changed.

What is Hong Kong's role in promoting sustainable fashion these days?

Hong Kong has a large competitive advantage. Hong Kong’s key advantage is that we have a long history in the textile industry - we were the main manufacturer, sourcing, supply chain. We have a rich technical know-how and we are on everyone’s supply chain.

Our challenge is that we have no processing capability in the city. Over 90 percent here is a service economy and we have no factories. The trash we produce only goes to landfills and we don’t have other solutions, while other countries don’t allow us to send our trash to them for processing. This is our challenge, but it is also the same for cities like New York and London.

We see this challenge very clearly and we have a lot of potential to contribute to the solution of such problems. Hong Kong manages and owns manufacturing capabilities. We have a huge involvement in the industry. On the other hand, why should Hong Kong be involved? Our value creation used to be labour, but now it’s service. Value creation can be these innovative solutions - we should build on our past success to develop these solutions.

"Fashion can be a service instead of a product."

Different segments of the industry have different reactions to a new solution. Luxury brands use traditional and proven materials, including leather, silk and cashmere. They are reluctant to downgrade their raw materials, so we have to see if we can make some innovations for them within the use of such raw materials.

On the other side of the spectrum, brands are more price sensitive to new raw materials, especially before we scale it up and we have to do value proposition. In the middle there are some segments that want to adopt but have concerns, like sporting brands who want to spread this message but want functionality at the same time. They have different concerns, so our research roles have to ensure we can address their different concerns.

Sustainability and calculability aren’t a charity case. We are presenting a business case, and this can increase brands’ market shares.

If CFOs can buy off your idea as a business decision, then it’s truly sustainable. Hong Kong’s contribution in sustainability is to make a business model.

Image by H&M Foundation.

By copying the embed code below, you agree to adhere to our republishing guidelines.