- About

- Topics

- Story

- Magazine

- In-Depth

- Picks

- Opinion

- News

- Donate

- Signup for our newsletterOur Editors' Best PicksSend

Read, Debate: Engage.

| July 31, 2022 | |

|---|---|

| topic: | Death Penalty |

| tags: | #death penalty, #capital punishment, #death row, #torture, #cruel and unusual punishment |

| located: | USA, Zimbabwe, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Syria, Somalia, China |

| by: | Gerardo Bandera |

This past week, the government of Myanmar executed four pro-democracy activists (the first execution in the country in over 30 years), including former-MP and rapper Phyo Zeya Thaw. Meanwhile, in Japan, a normally pacifist country, the culprit of a stabbing rampage in 2008 was hanged, despite international pressure from activists to abolish capital punishment. More grimly yet, in March of this year, Saudi Arabia executed 81 people in a single day. This trend extends to countries that are regarded as more humane: in the US state of Oklahoma will begin an execution spree in September, scheduling one execution every month between then and December 2024 (25 executions total). These recent occasions have spurred activists to decry the excessive use of inhumane capital punishment, especially in cases where the culpability of the defendant is not confirmed.

Capital punishment, in countries where a strict checks and balances system is not in place, can easily be misused or expoloited by government officials for fascist abuses of power. In others, it is used as a demonstrative warning for citizens about what offences are intolerable or compromise civil order, which will not be overlooked or forgiven. Whether this looming threat truly prevents crime and abuses to human rights more than it participates is widely contested among civil activists.

The death penalty, or capital punishment, is the state-enacted execution of a person as punishment for a capital crime. Countries that allow the use of capital punishment have, for the most part, defined capital offenses, the punishment for which is death. In most cases, capital punishment is reserved for extreme crimes, such as terrorism, mass murder, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and sometimes murder and rape.

However, in totalitarian regimes, or even in countries where legal systems are not sturdy, capital punishment can be used to silence dissent or to punish smaller crimes like drug posession, desertion, or even cowardice. Singapore, for example, hanged a man this week merely for cannabis trafficking. For this variation in mortally punishable crimes, many activists argue that governments should not hold this lethal punitive weapon that can easily be abused.

Histories of capital punishment can be traced back to some of the earliest civilisations. The Torah or Old Testament, for example, authorises the death penalty for crimes like murder, the practice of magic, kidnapping and even the violation of the Sabbath. In Ancient Greece, the death penalty was instated under Draconian law as far back as 621 B.C., and later, Plato defended capital punishment as a means of purification for the defilement of a crime.

Capital punishment survived well past these civilizations, and could be found in infamous cases, like widesweeping witch trials in Europe and North America, the punishment of homosexuals for sodomy in early Islamic caliphs, and the mass executions of King Henry VIII in England, who is said to have despotably executed over 72,000 during his reign. These examples show how, in the hands of tyrants or misguided ideas and religions, capital punishment is a dangerous tool when it falls in the wrong hands. In fact, genocides and mass executions are often justified as punishment for some crime or transgression of ideology.

By the end of 2021, a total of 108 countries had abolished the use of the death penalty, more than two thirds of the world; nevertheless, 55 countries still have the death penalty in their penal toolbox. Most notable are the USA, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Japan, Somalia, South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

In 2021, recorded state-sanctioned executions totalled 579, while 2,052 death sentences were served worldwide. Iran was the biggest executioner, accounting for 314 people, followed by Egypt (83), Saudi Arabia (65), Syria (24), Somalia (21) and the USA (11). This, however, does not include the real number of executions committed in China, which is estimated to be well over 1,000. While most of these countries performed their executions by hanging and shooting, the USA, China and Vietnam preferred lethal injection, while Saudi Arabia continues to use beheading as their method.

Despite its reputation as a humanitarian leader, the United States has not abolished the death penalty at the federal level, instead allowing states to determine their approach to abolition and execution. 27 US-states continue to allow the death penalty including:

Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah and Wyoming.

The US Federal government and military also retain the ability to condemn someone to death. Texas, Oklahoma, Florida and Virginia are the states that have used the death penalty the most.

Many abolitionist movements from the past 500 years can be accredited to the thought of Cesaria Beccaria’s treatise “On Crime and Punishment” in which he argues that capital punishment is the “war of a nation against a citizen” and that it hypocritically commits the same crime that it seeks to punish or deter. Beccaria influenced many luminaries, like Thomas Jefferson and Voltaire, and his arguments remain at the core of abolitionist movements.

Since then, many modern countries have completely outlawed capital punishment. The UK abolished it after a 5 year experiment (to verify its effectiveness on deterrence) in 1969; Australia followed shortly after in 1973 and Canada in 1976; France completely abolished it in 1981. By 2003, the European Convention of Human Rights instated Article 13, which forbids the use of the death penalty for any offence, which was expected to be ratified in any European member-states.

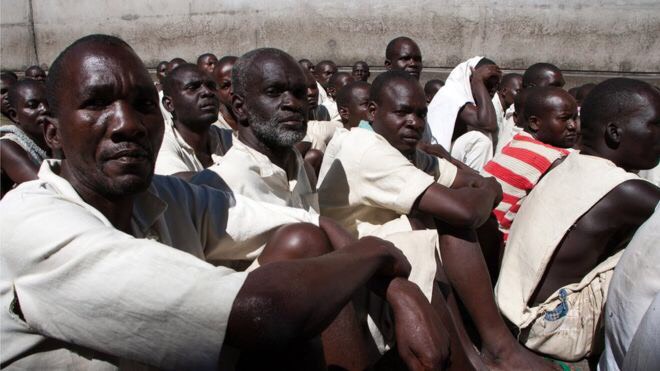

Despite the overall trend towards abolition, the movement is often met with resistance on the way. Zimbabwe offers the perfect example, as former-President Langu - who favoured abolition and provided clemency to hundreds of convicts on death row - faced resistance in 2016 from his constituents, whose attitudes strongly defend capital punishment as a tool to make criminals pay for their offences and to prevent more criminality.

The most obvious argument for keeping capital punishment instated is that it serves to deter serious crimes like murder and terrorism, rightly punishing them to prevent new ones. However, opponents of this view state that criminals who are set on committing a crime do not verify the possible punishment for it, and sometimes do not even care what punishment they may receive for it. A person set on committing mass murder or terrorism has already accepted that they may perish while they commit the crime so the threat of death, one way or another, changes little for them; in fact, it may give them the ending that they wanted and creates them into celebrated martyrs, encouraging their followers to avenge them.

Other arguments state that capital punishment reduces the finiancial burden of keeping criminals alive in prison systems at the expense of tax-payers. Opponents of this view contend that the protection of the human right to life should not be determined by cost-cutting punishments and also stipulate that inmates on death row represent less than 1 percent of convicts, the execution of which would result in negligible savings to taxpayers.

Photo by Hédi Benyounes

By copying the embed code below, you agree to adhere to our republishing guidelines.